Looking at, for and with desire in Contempt.

by Jennifer Stewart

[Part of VINYL IS HEAVY's Bastille Day celebration. Click here to see our index. Click here to view all the entries at once. Ed's note: Jen plans a few revisions which she hopes to finish sooner rather than later but in the spirit of this enterprise, I thought I'd offer her initial thoughts for now since they're a good starting point and valued contribution to our little project here.]

Le cinéma substitue à notre regard un monde qui s'accorde à nos desires. Le Meprise est l’histoire de ce monde.

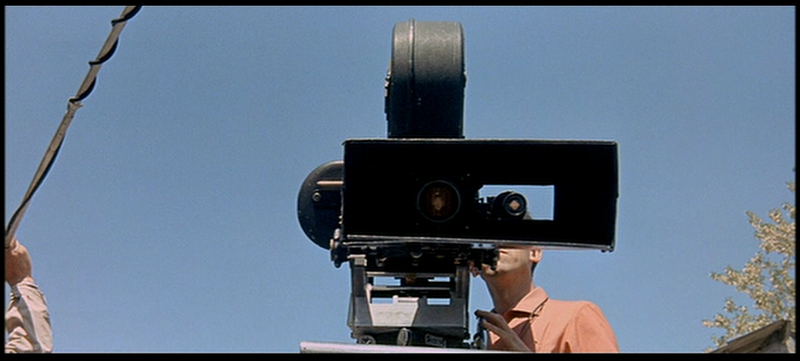

As Contempt’s camera turns on us, its narrator ends the prologue with this claim about cinema and what awaits us on the other end of the lens. Since seeing this stunning-looking film at the Castro Theatre, on a rare hot evening in San Francisco a few weeks ago, I’ve been thinking about its self-proclamation. What follows are my current thoughts – still developing, not quite a reading, but some thoughtful rumination on film and desire. If cinema substitutes for our gaze a world according to our desires, one immediate question should be: how does film know what we desire?

The usual answer is that film does this manifestly. Here, we’d say film presents bodies and dynamics we want to see played out because these confirm stories that offer to stabilize desire into objects and roles we can imagine ourselves in. But it doesn’t take much to see how unsatisfying such an answer quickly becomes, especially for a film like Contempt. If anything, Contempt stages conflicts and problems of desire, collateral with problems and conflicts of film-making. We look at Brigitte, to be sure, and we see her as the kind of beautiful thing film can present. But her presentation is exactly the key, for she (and everyone else in the film) is not a character (to be “identified” with or not) so much as a portrait of the consequences of exchanging (or, failing to exchange) the looks that confirm an understanding of loving and/or desiring, and of being loved and/or desired. What happens between Paul and Camille, arguably, is a breakdown in their ability to return a sustained world between them where desire and love is signaled and consummated. In that moment where Paul blithely hands Camille over to Prokosch, sending her alone with him to his villa, Camille shuts off. The camera shows us the whole silent exchange; a watershed moment between this couple, the precipitating consequences thereof which the rest of the film unfolds. What’s beautiful about Contempt is that this visual language of desire is told as embedded in a world saturated with cinema. It presents the texture and reference of cinema everywhere, as living or naturalized mythology on the walls and in the livelihood of its characters. Contempt enriches the idea of a world in which desire occurs, by showing its fragility.

So why not say, film stages not a manifest but a latent constitution of desire. I mean, it is the emblematic form of cinema itself - a camera 'seeing' in a frame - which has effected the substitution, because it provides a world in which our gaze is directed. The substitution then is simply a world exchanged for a framed world: a world scoped out for us. A world showing us where and how to look. Put that way, pornography is cinema’s logical extension, because it leads and places the eye exclusively (in sex acts made graphic on the screen) – you have no where else to look.

Contempt plays with this. Camille makes a game of asking Paul to look at pieces of her in the mirror – her ankle, her knee, he thighs, her breasts, her face – and asks of each how he likes them. They look into a mirror out of shot while the camera roves along Camille’s naked body. In both senses a body is framed before we look upon it as presented for desire. If pornography is one end of this scale of directing the eye, cinema more usually arouses through affective implication: through shots whose vantage points are themselves part of the suspension of a film’s (if you like) meaning. By suspension, I mean an affective pregnancy, of the fact that the experience of watching will quite literally move through our bodies; provoking, stimulating, arousing, paralyzing, dulling. This is to some extent because watching will simultaneously be an active process of conscious and unconscious connections, as we draw out resources with which to track the film. Most of these will be fleeting and flashed, multifarious and peripheral. And, different occasions of viewing a film can triage a different stream of this fluid. My point is that suspension nicely captures how unqualified watching can be. Its affective power lies in this suspension, for it is this affect we resolve or try to tell, when we try to speak (coherently) about a film.

Contempt is a sequence of suspended desire. The film within it trying to be made (The Odyssey) collapses, and the consummation of desire and love between Paul and Camille collapses, but Contempt looks on.

It is one of the best one movies, I think that the movies today are so different but in the past were ever good.

ReplyDeleteThis article is so interesting and so appropriate to read so careful!22dd