Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Saturday, September 27, 2008

Found Facts. August 2008.

by Ryland Walker Knight

I really had to work to make this fit. The final edit I was set on at first was 11:30, which is too long for YouTube, apparently, so I went in and played with stuff. I think it still works, just different. And, twice as long as the previous installment means twice as many jokes. That means the quality suffers again, unfortunately, and this one really does look better on my HD as it has more "natural" spaces and light. Still a series of naive love letters, this one is elevated from pure nostalgia, I hope/trust, by all the goofy stuff thrown in -- like all those rocks.

SITES SEEN =CZ, Berkeley =The Trappist, Oakland =Cuy's car, Berkeley =Cam+Mego's pad, San Francisco =Berkeley streets =Yuba River, 20 minutes west of Nevada City =Rach's dad's backyard, Sonoma =all thrown together

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

3:30 PM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: comedy, family, film, Found Facts, linkage, rwk, west coast

Every day I'm hustlin...

[Thanks for the laughs, and the popcorn. You were too cool. Look to DH, as ever, for a round-up.]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:45 AM

1 grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, blogging, linkage, Paul Newman, rwk

Friday, September 26, 2008

A gallery of refusal: Xiao Wu

by Ryland Walker Knight

An accomplished if ragged debut, Jia’s first feature,Xiao Wu (or Pickpocket), itches around restless, looking for things—an escape, maybe—with its eyes cocked at and always reigned in by the repeated traps of the social.

Today marks my first contribution to The Auteurs Notebook, which you can continue reading by clicking right here. It's a little ditty about Jia Zhangke's debut feature, Xiao Wu, which I saw at the PFA last week. I'll be seeing his 2007 documentary, Useless, tonight at 6:30pm.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

7:15 AM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: blogging, China, criticism, Jia Zhangke, linkage, rwk, The Auteurs, theft

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

Sing seeing, sing.

by Ryland Walker Knight

I visited Daniel in class yesterday and made some images; then I cut them up. Since my internet is so slow I uploaded a smaller file, which combs. And yet, again, I'm thrilled by the "failure" of this camera. It's another announcement, another event. I love how this version is different than the 700MB file I exported from iMovie, how both those are different than the raw file I uploaded onto my hard drive, how different all those are from when I was sitting there. Something I thought while sitting there, sweating in that plastic bucket next to the window: this adventure of perception continues to interrupt itself. Every blink is a cut, every step a zoom, every gesture made makes spaces different and the effects play like affects across the face. So what happens when you don't see Daniel's face here? Wait: we see his profile, his hands; his body to begin and end the clip. But it's dark. Where is the face? Behind Daniel, on the wall? That's not his face; it's his boy's face. His face is this pacing, this boiling gesticulation. As he would say, this style, this way of going. Style, of course, being a performance—of one's multitudes, of every angle brought to bear, of every memory made flesh. Things get tricky, then, when all he's doing is talking about seeing and all you want to do is look at the boy and his chocolate, not that flitting figure below.* But, of course, his figure forms the geometry of gazes, too. He even sneaks a peak at me twice, creating yet another announcement-event, and his language gets dizzy, too, there at the end, as he falls into-through that word: seeing. Seeing sounds like being, sure, but it sounds like sing, too. His waterfall of "seeings" sounds like an imperative to sing, sing seeing, sing. Live this seeing.

[If the veoh video above doesn't load for you, you can watch this on youtube: click here. The veoh looks better, and sounds better, but youtube is, well, damn reliable; what's weird is the youtube compression makes this feel more analog (warmer) than the veoh player, which still holds onto the cold of the digital comb.]

[Looks like veoh is just wrong, or too fussy. So I went ahead and embedded the youtube clip. If you want to try the veoh clip, and get irked, click here. Also, you can track Dsee's class via its dedicated blog, which is called -- you'd never have guessed it -- Seeing Seeing.]

*Try to note the lift before the first edit.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

A conjunction of quotations #2

— edited by Ryland Walker Knight

1.

The modern fact is that we no longer believe in this world. We do not believe in the events which happen to us, love, death, as if they only half concerned us. It is not we who make cinema; it is the world which looks to us like a bad film. Godard said, about Bande à parte: 'These are people who are real and it's the world that is a breakaway group. It is the world that is making cinema for itself. It is the world that is out of synch; they are right, they are true, they represent life. They live a simple story; it is the world around them which is living a bad script.' The link between man and the world is broken. Henceforth, this link must become an object of belief: it is the impossible which can only be restored within a faith. Belief is no longer addressed to a different or transformed world. Man is in the world as if in a pure optical and sound situation. The reaction of which man has been dispossessed can be replaced only by belief. Only belief in the world can reconnect man to what he sees and hears. the cinema must film, not the world, but belief in this world, our only link. The nature of the cinematographic illusion has often been considered. Restoring our belief in the world -- this is the power of modern cinema (when it stops being bad). Whether we are Christians or atheists, in our universal schizophrenia, we need reasons to believe in this world.

— Gilles Deleuze

2.

You have to be a fake first.

— Jonathan Lethem

3.

All films are about the theatre, there is no other subject.

— Jacques Rivette

4.

Run to the lights of the city.

These moments passing will be there.

Run to the lights of the city.

This dance will last us forever. Forever.

— Cut Copy

5.

Now, too, the rising sun came in at the window, touching the red-edged curtain, and began to bring out circles and lines. Now in the growing light its whiteness settled in the plate; the blade condensed its gleam. Chairs and cupboards loomed behind so that though each was separate they seemed inextricably involved. The looking-glass whitened its pool upon the wall. The real flower on the window-sill was attended by a phantom flower. Yet the phantom was part of the flower, for when a bud broke free the paler flower in the glass opened a bud too.

— Virginia Woolf

6.

The color is yet a variant in another dimension of variation, that of its relations with the surroundings: this red is what it is only by connecting up form its place with other reds about it, with which it forms a constellation, or with other colors it dominates or that dominate it, that it attracts or that attract it, that it repels or that repel it. In short, it is a certain node in the woof of the simultaneous and the successive. It is a concretion of visibility, it is not an atom.

— Maurice Merleau-Ponty

7.

And then black night. That blackness was sublime.

I felt distributed through space and time:

One foot upon a mountaintop, one hand

Under the pebbles of a panting strand,

One ear in Italy, one eye in Spain,

In caves, my blood, and in the stars, my brain.

There were dull throbs in my Triassic; green

Optical spots in Upper Pleistocene

An icy shiver down my Age of Stone,

And all tomorrows in my funnybone.

— John Shade

8.

This girl she didn't know where she was goin' or what she was gonna do. She didn't have no money or nothin'. Maybe she'd meet up with a character. I was hoping things would work out for her. She was a good friend of mine.

— Linda

9.

His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly's wings. At one time he understood it no more than the butterfly did and he did not know when it was brushed or marred. Later he became conscious of his damaged wings and their construction and he learned to think and could not fly away any more because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless.

— Ernest Hemingway

10.

I believe that we are lost here in America, but I believe we shall be found. And this belief, which mounts now to the catharsis of knowledge and conviction, is for me—and I think for all of us—not only our own hope, but America's everlasting, living dream. I think the life which we have fashioned in America, and which has fashioned us—the forms we made, the cells that grew, the honeycomb that was created—was self-destructive in its nature, and must be destroyed. I think these forms are dying, and must die, just as I know that America and the people in it are deathless, undiscovered, and immortal, and must live.

I think the true discovery of America is before us. I think the true fulfillment of our spirit, of our people, of our mighty and immortal land, is yet to come. I think the true discovery of our own democracy is still before us. And I think that all these things are certain as the morning, as inevitable as noon. I think I speak for most men living when I say that our America is Here, is Now, and beckons on before us, and that this glorious assurance is not only our living hope, but our dream to be accomplished.

I think the enemy is here before us, too. But I think we know the forms and faces of the enemy, and in the knowledge that we know him, and shall meet him, and eventually must conquer him is also our living hope. I think the enemy is here before us with a thousand faces, but I think we know that all his faces wear one mask. I think the enemy is single selfishness and compulsive greed. I think the enemy is blind, but has the brutal power of his blind grab. I do not think the enemy was born yesterday, or that he grew to manhood forty years ago, or that he suffered sickness and collapse in 1929, or that we began without the enemy, and that our vision faltered, that we lost the way, and suddenly were in his camp. I think the enemy is old as Time, and evil as Hell, and that he has been here with us from the beginning. I think he stole our earth from us, destroyed our wealth, and ravaged and despoiled our land. I think he took our people and enslaved them, that he polluted the fountains of our life, took unto himself the rarest treasures of our own possession, took our bread and left us with a crust, and, not content, for the nature of the enemy is insatiate—tried finally to take from us the crust.

— Thomas Wolfe

11.

By a paradox that is only apparent, the discourse that makes people believe is the one that takes away what it urges them to believe in, or never delivers what it promises. Far from expressing a void or describing a lack, it creates such. It makes room for a void. It that way, it opens up clearings; it "allows" a certain play within a system of defined places. It "authorizes" the production of an area of free play (Spielraum) on a checkerboard that analyzes and classifies identities. It makes places habitable.

— Michel de Certeau

12.

After all, one can only say something if one has learned to talk. Therefore in order to want to say something one must also have mastered a language; and yet it is clear that one can want to speak without speaking. Just as one can want to dance without dancing.

And when we think about this, we grasp at the image of dancing, speaking, etc.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

13.

Taking seriously.— In the great majority, the intellect is a clumsy, gloomy, creaking machine that is difficult to start. They call it "taking the matter seriously" when they want to work with this machine and think well. How burdensome they must find good thinking! The lovely human beast always seems to lose its good spirits when it thinks well; it becomes "serious." And "where laughter and gaiety are found, thinking does not amount to anything": that is the prejudice of this serious beast against all "gay science." —Well then, let us prove that this idea is a prejudice.

— Nietzsche

14.

This revolution is to be wrought by the gradual domestication of the idea of Culture. The main enterprise of the world for splendor, for extent, is the upbuilding of man. Here are the materials strewn along the ground.

— Emerson

15.

Wait!

All-right.

Give me every little thing.

And don't stop.

— The Juan Maclean

[Leading image: "What will be play now?"]

Monday, September 22, 2008

VINYL IS PODCAST #2: Future calendar highlights, with Brian Darr.

by Ryland Walker Knight and Mark Haslam

RWK here. This episode: we're joined by local hero and blogging buddy Brian Darr, of Hell on Frisco Bay, to talk the upcoming rep calendar. Of course, any talk about movies, especially a talk meant to cover so much, will spill over into other topics and other films other than the films and film series at hand. We even divert into a talk about Cut Copy and their upcoming, sold-out show in San Francisco on Sunday, October 5th, as well as Gus Van Sant and Michael Haneke, among other things, including my trip to Telluride, again, of course. Speaking of: a big apology to Howie Movshovitz, one of the real cool pair of moderators/hosts for our Student Symposium (the other: Linda Williams), whose name I totally blanked on during our recording session. If you make it that far, you'll hear me grasping, failing, griping -- and coming up with Harvey. The reason I didn't follow Brian's "on air" advice and splice in some kind of edit correction is because I just want to let the tape run. As I say at one point, this is not planned. I like it that way. I did a better job of projecting my voice this week, I think, which might make it easier to listen to, but I still dig how un-NPR we are on these experiments. Thanks for indulging us. We're still trying to make this mic work, but it's tough. I've got a (pretty cheap) directional mic so it really needs you to talk at it -- it doesn't record the space of the room all that well -- and, as is natural, Brian and Mark turned towards me to talk, to perform our conversation, so their voices are a little lower than mine in the mix. So turn it up.

Once again, we've got some dance music to introduce and end the episode, and you can grab it here. Yes, it's Cut Copy. Oh, you want a link to the podcast itself? Well, you can click this link to load iTunes and subscribe there or you can click this link to find our podomatic page or you can click this link to download the file directly from podomatic or you can click this link to subscribe to the RSS feed. The choice is yours. And, of course, please tell us things in the comments. If you're in the Bay, tell us what you're most interested in, what we may have forgotten. For one, I know there's a certain en vogue auteur we didn't talk about that will be exhibited in San Francisco in October. Do you know who? Where? When, exactly?

Since this episode is about twice as long as the previous one, and I always appreciate Rob's breakdowns, here's some minute markers for our rambling talk:

- 0:00 - 7:00: Intro, Jia Zhangke.

- 7:01 - 9:45: Envisioning Russia.

- 9:46 - 11:11: Manoel de Oliveira.

- 11:12 - 12:12: David Lean at PFA and The Castro (Lean Sundays in October), even a mention of Film Forum.

- 12:13 - 17:05: Godard in the 60s and Jean Eustache and Cut Copy.

- 17:06 - 18:36: The recent Milos Forman series that Brian enjoyed and wanted to highlight, if briefly.

- 18:37 - 20:08: Ning Ying's residence at PFA and the current BAM exhibit Mahjong: Contemporary Chinese Art from the Sigg Collection.

- 20:09 - 24:30: The current Alternative Visions line up of Avant-Garde Cinema, which will feature the Bay Area premiere of RR, which has Brian and me excited given James Benning's reputation and the words from Toronto, like those of Darren Hughes.

- 24:31 - 30:00: Running down the current Castro line up with a diversion to allow us some time to talk about this brand of cinephilia that privileges theatrical screenings over home screenings. We pick up a thread of last week, too, to talk about audience reactions, which then leads to some brief thoughts about Burn After Reading and a few trailers: W. (that's not the version we saw) and Milk.

- 30:01 - 38:45: The talk of those trailers spills into talk about Gus Van Sant and Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Haneke and James Franco. Here's that Reverse Shot issue I mention; here's Michael Koresky on Psycho, and mine on Cowgirls. BTW: Milk will premiere at The Castro on November 26th.

- 38:46 - 40:50: Lola Montez revival at the Castro.

- 40:51 - 44:50: The Mill Valley Film Festival, including talk of the tributes to Harriet Anderson and Paul Schrader and Happy-Go-Lucky and Kelly Reichardt.

- 44:51 - end: Goodbyes and some parting Cut Copy.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

12:45 AM

6

grooves

![]()

Labels: Cut Copy, guest, Gus Van Sant, Haneke, Hitchcock, Jia Zhangke, linkage, MH, PFA, rwk, VINYL IS PODCAST

Saturday, September 20, 2008

Cutting into the world: La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc tears and tears, bleeds.

by Ryland Walker Knight

Dreyer cuts space apart to the point that it isn't even something to talk about. La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc has no need for spatial (or, for that matter, temporal) terms. Of course we're given the unity of the single day, and the stations of the cross, as it were, but every image in the film is expression; there's no real interest in representation. "The close-up is the face." It's a film of faces big and small and brimming and dead and burnt and crying and alive and inanimate. Hooks jutting across a frame are a face of terror and pain; the stake aflame with a cross behind, a face lifting us out of the world; the sacrament raised in prayer, a face of dignity; Jeanne's torn blanket a metonymic version of her, an echo of her arm's pump. It's as pure a film, as purely affective a film, as I have ever seen. But its grammar is miles from what PTA's been developing. In fact, not that this is fair or equivalent, his grammar seems much more akin to something like what Tony Scott habitually falls just short of despite his best efforts. It helps to have something to say, but, and I mean this, those last three Tony Scott movies, tied as they are to plot, deliver a lot of goods in purely formal registers; it reaches an apogee in Deja Vu's little room, and then loses itself, but pretty much the whole of Domino is fascinating, lively, expressive filmmaking. And Dreyer edits fast. (Much more interesting, though, than Tony over there.) In ten seconds you can see a baby suckling, Jeanne clutching a crucifix, the baby pull away from the tit, a man without a face pull away the cross from Jeanne's clutches, and the baby returning to the milk. A tidy circuit of give and take. It's phenomenal, really. I can't believe it's taken me so long to find my way to this master of cinema. Also, a hilarious footnote here: what a political film!

[We need reasons to believe in this world, even as we rend it open. Find more by clicking here.]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

11:30 PM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: affect, Deleuze, Dreyer, faith, formalism, images, linkage, mise-en-scene, Paul Thomas Anderson, rwk, screenshot, special, Tony Scott, violence

Monday, September 15, 2008

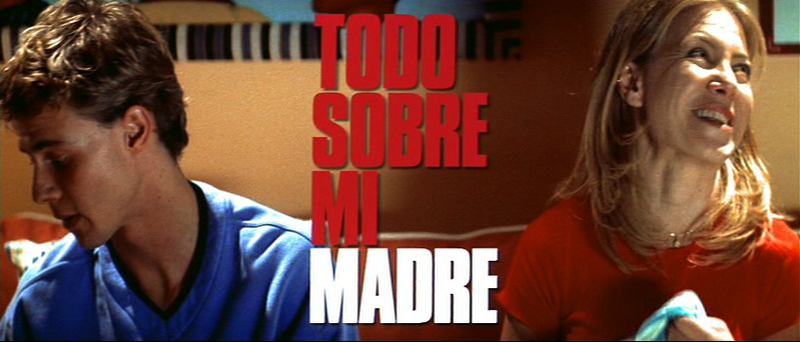

Melodrama Mondays: All About My Mother

by Mark Haslam

"Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience . . . We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy's impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character's pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside."

-David Foster Wallace

When it was released in 1999, critics hailed Todo sobre mi madre (All About My Mother) as an indication of Pedro Almadovar's "maturation" as a filmmaker. Return to those reviews and find the likes of “sobriety” and “depth” and “conviction” peppered about as evidence of this newfound maturity—all of which are placed in stark contrast to, as Andrew Sarris remarked in The New York Observer, “Almadovar's overtly gay sensibility..., canny distancing...[and] flair for voluptuous color compositions and sinuous camera movements” that made his films (cringe) “guilty pleasure[s].” Return to the film itself, however, and these estimations don't seem quite right: to shortchange Almadovar's style in this way is to ignore the fact that it's absolutely present in Todo. I'll concede—not that I'm actually debating with nine year-old reviews, but I'll concede that Todo sobre mi madre doesn't have the manic feel of Almadovar's previous films. But the style, that visual “flair,” as nebulous and uncertain as that word is, most certainly remains. I'll go so far as to say that it's exactly that “flair” (and I'll search for a better word in a moment), rather than some sort of self-restraint or self-censuring on the director's, is part of what makes Todo sobre mi madre what it is—that made that one teary-eyed critic shout, with the credits rolling, “Wring me out!”

What then is this “flair”? It's pretty easy, in naming it, to deploy terms like pizazze and passion and grandiosity, and even easier to makes terms up, like over-the-topness, and, you know what, they're all decent descriptions of Almadovar's style. Yet we know, at the same time, that they're insufficient, that they don't really describe the thing we're feeling: a feeling that I see as a trait of all melodrama, a feeling that I hope to explore more over the course of this column. I think Almadovar tries to elaborate on this style—our feeling—in the first twenty minutes of the film, which form a sort of prologue, an introduction to the narrative that begins after them. I want to focus specifically on the sequences that lead to the first death in the film, the incitement of narrative, that of Esteban, only son of our main character, Manuela. So let's see what it is we're feeling. Let's try to recapture it, as best we can. Let's watch.

It's the night of Esteban's seventeenth birthday. He sits, writing, in a cafe, waiting for his mother to arrive. In the background is a giant poster for the play he and Manuela are about to see. The focus of the poster are the two massive blue eyes of Huma Rojo, staring at Esteban, at us. Indeed, the poster (the eyes) begins in focus, shifting second to Esteban in the foreground (a perspectival shift seemingly enacted by Huma's eyes). Manuela comes in, looking for her son. The head of Huma (which could almost be confused for Manuela's) looms behind and dominates her in the frame. And yet we see, now, with Manuela in the picture, the 'pixels' that compose the poster—that is, we see the artifice. Or, better still, we see the things that make it big, at the very moment that we note the bigness of the shot itself: Manuela's bright red coat and those red red lips, even the pixels are red: so, we're not only seeing different (practically competing) red things, we're seeing Red, itself: we're zooming in to the point that we just see Color: or, we zoom in just enough that we're shown the abstractions that composes the image. The image, in this way, interrogates itself. And, really, isn't that what Huma's eyes seem to be doing? Interrogating. Observiving. But that interrogation isn't simply the interrogation of self-reflexivity. This is why Almadovar begins the film with consciousness. Here, to me, is the brilliance of these opening minutes, for the self-awareness (mostly) disappears after them, so that it's not so much deconstruction as it is construction we witness—a building up to and of the film. We have to see, in the first twenty minutes, the production of fictions, but especially of this fiction. (Recall Esteban, writing down what is presumably the title of the film—a moment of inspiration—and then immediately after the title appearing on the screen.) Yet it's a fiction that hasn't really begun. That won't begin until Esteban dies.

What, then—or is it, who?—is being interrogated? Of course, there's no single answer to that question. Two possible answers, though, would have to be: Melodrama and the Mother: or, consolidated, the figure of the mother in melodrama. Because it's Manuela's presence that seems to give away the artifice. Her entrance into the frame, the camera's focus on her, does not give space to the poster. But it is also the poster that threatens Manuela's hold over her son, precisely because it's big, because it's artificial. As we continue after the play, Esteban wants to get Huma's autograph. He and Manuela wait by the stage door. At her son's request, Manuela acquiesces to tell Esteban “all about [his] father.” Excitedly, joyously and lovingly he kisses Manuela on the cheek—but at that moment, Huma appears from backstage, the red of her name now fully apparent in her vibrant hair. How can Manuela compete with this red? She grips her son's arm, as if to hold him in place, but he runs to Huma's car. Through the window, they stare at one another, and the car drives off. Huma turns, peers through the back window. Her eyes (those eyes—to say nothing of those lips) appear clear through the pouring rain. Beacons whose pull is irresistable to Esteban, and so he takes off after them.

The camera pulls away from Manuela, but whose perspective is this? Is this the final glance back that Esteban never gave to his mother? Or is this Huma's perspective from the car? Is it Manuela she's been looking at? Both and neither: the camera communicates from its own 'perspective'. First an avenue for interrogation (possessing a certain skepticism, a sentience or awareness), it now enters into a realm of emotion. It emotes: pulling away from Manuela, it focuses on her, sympathizes with her. That move is, to me, nothing short of heartbreaking. Almadovar's style, the style of melodrama, is so much about form, not content, as the communicator of emotion.

We switch then into Esteban's POV as he's hit; the camera spins, twirls, lands on the ground, and we get the final image, sideways on the wet pavement, of Manuela, her son now truly gone from her grasp, running to him.

What was Esteban seeking? Huma is the objet petit a, yes, but I think it's actually performance he's seeking. That is the unattainable object of desire. Esteban seeks the performance in (and of) life (his mother acting in her youth, and now, simulating the transplant situations). Huma is simply the manifestation of that desire. So it makes sense that Esteban seems to be writing this film, that he's Almadovar's alterego, and that his death represents a passing into narrative: Manuela sets off to find Esteban's father, to fulfill her promise to tell “all about [his] father.” (Note, though, that immediately after Esteban dies, he passes into voice over, a sort of ghostly presence that comes from 'behind' the camera.)

The awareness that we see in the opening minutes of Todo sobre mi madre is not the awareness of the post-modernist, ever distant, ever desiring to expose artifices; not really. It is instead an awareness that emotion is in construction and form. Melodrama is a genre whose tropes are so familiar and so transparent to us, but it's a genre whose form acknowledges and delights in these transparencies, these fictions and performances, and presents them as though they weren't transparent at all, as though they were every bit as real. The argument laid out in these first twenty minutes is an argument for the validity of artifice as a window into experience. Think of Agrado's speech about her various cosmetic surgeries. Or of Manuela, crying in the performance of A Streetcar Named Desire because of Stella, because she's lived Stella's life. Almadovar encacts, here, the vicarious experiences that melodrama (and fiction in general) offer to us: the “experience of suffering,” as David Foster Wallace said, that brings us to art. An experience that may be impossible in reality, but on which reality desperately depends.

[Look at Ryland's companion image essay.]

Posted by

M. D. H.

at

6:30 PM

1 grooves

![]()

Labels: color, criticism, formalism, images, Melodrama Mondays, MH, Pedro Almodovar, screenshot

VINYL IS PODCAST #1: Almodovar, Ray, Melodrama

Telluride #4

UPDATED: iTunes link.

by Ryland Walker Knight and Mark Haslam

Here we are, joining the internet radio fray, with our first attempt at a podcast. This is an introductory test run in a lot of ways but I think you might get a kick out of the Eddie Huntington song we've chosen to use as intro/outro music this week. We experimented with a lot of hosting options and finally stumbled on the really cool site, podomatic, thanks to my friend Daniel's usage (he's "casting" his last course at UC Berkeley and you can listen here). We've got our own page there: CLICK HERE TO SEE IT and subscribe to the RSS and, if you like, download the file for your ride into work. As for this episode, there's a lot of rambling, a lot of dead air, and my nasal voice -- all great selling points. Please, listen! You might have guessed, but we talk about Pedro Almodovar, Nicholas Ray, and melodrama with detours into some talk of my Telluride trip and Slavoj Zizek and a little bashful scolding (with a smile) along the way. And, as the song says, don't be shy, let yourself go with the attraction, and talk at us in the comments. If you want the song, you can grab it here and dance your butts off (although, if the owners request its removal, we'll happily and heartily comply).

"Live in the world, or something."

UPDATE: If you want to subscribe in iTunes, please click here and enjoy. To those who already have, we thank you, and await your suggestions, comments, critiques, gripes, enthusiasms. Again: I hope we get liven things up a little more on the next episode. If anything, there will be another (smart, kind) voice to break up our monotone madness.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:55 AM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: linkage, melodrama, MH, Nicholas Ray, Pedro Almodovar, rwk, Slavoj Zizek, Telluride 2008, VINYL IS PODCAST

Saturday, September 13, 2008

For good or ill or plain ego trap tricks: Favorites.

by Ryland Walker Knight

VINYL IS FAVORITES

I've said before to a lot of people that lists make me itch. But before I went to Telluride I started this Text Edit file that listed favorites for every year. I'm not exactly proud, nor exactly ashamed, of these lists, but I remembered that when I started reading film blogs and online criticism in general I got a lot out of looking at lists. I got a lot of good ideas. And while I'm nowhere near as well versed as others out there (like, say, Michael Sicinski or Ed Gonzales; two dudes who pointed me towards a lot of cool stuff), maybe this will satisfy somebody's curiosity. If anything, it will please my buddy Michael Kansberg. For now I only put up the last three decades because they're the easiest, and because they cover how long I've been around this world, and because I want to fill out the others some more before I offer them up. I had the impulse to be as honest as possible and throw up all the unfinished lists but then I got nervous and self-conscious and I reigned it in a bit. Not sure when the rest will "go live" but they'll probably get going sometime soonish. And, please, tell me things. I like to learn.

Friday, September 12, 2008

Post-punk, mainland style. Jia Zhangke retro at PFA.

by Ryland Walker Knight

Unknown Pleasures: The Films of Jia Zhangke begins tonight at PFA with a screening of Still Life at 6:30 followed by Dong, with the short Our Ten Years, at 8:45. I'm new to Jia, but I love me some Joy Division (see sidebar), so the first things that popped to mind when I first heard of this Chinese auteur are those Manchester post-punks, which makes the series' title that much cooler. Spread over a month of screenings, the PFA will exhibit all Jia's features from Xiao Wu (Sept 18) through Useless (Sept 26). Plenty has already been written about Jia across the interwebs but, to drum up tonight a little more, here's a list of Still Life reviews, collected by Michael Guillen. As is my practice, I've not read much but cursory notes about why Jia is important (I've got my cocktail party knowledge), so this will be another learning experience. What I do know, and what intrigues me, is his interest in documentary fiction (I feel there should be a slash or an n-dash in between those terms, like, always) and digital (a recent turn in his work), both pet obsessions of mine ever since Pedro Costa rocked my world earlier this year. That, and I'm excited all my missed opportunities with Still Life's recent run will be absolved, and I hear he's into performance as well. I'll have to wait until October to see Unknown Pleasures (3rd) and The World (8th) and Platform (15th) on that big screen but I trust tonight's double bill will get me jazzed and primed. And, failing a trip to the art house, all three are available on Netflix. His Beijing Film Academy thesis film, Xiao Shan Going Home is not readily available for home viewing (for most viewing), and its Bay Area premiere will be accompanied by the short In Public on September 19th.

For more, read Hoberman (and again), Andrew Chan, Michael Koresky, Zach Campbell, Kevin Lee, Girish and pore over Harry Tuttle's links at Unspoken Cinema. I'll try to add to this conversation as the month progresses. [Pix stolen from all over.]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

9:05 AM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: blogging, Jia Zhangke, Joy Division, linkage, PFA, rwk

Tuesday, September 09, 2008

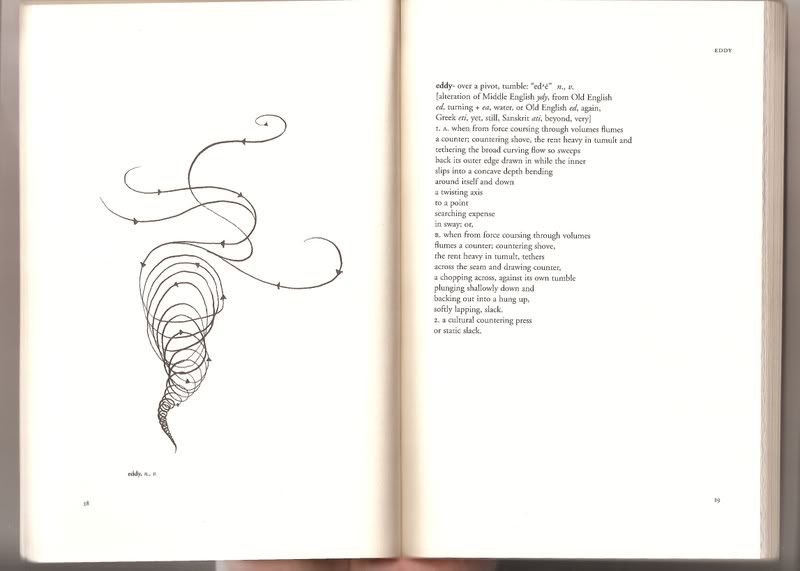

Poem for the month. "eddy"

[+ some gulls and ghosts]

[Click to enlarge. Text retyped as approximate as possible.]

___ ___ ___

eddy- over a pivot, tumble: "ed´ë" n., v.

[alteration of Middle English ydy, from Old English

ed, turning + ea, water, or Old English ed, again,

Greek eti, yet, still, Sanskrit ati, beyond, very]

1. A. when from force coursing through volumes flumes

a counter; countering shove, the rent heavy in tumult and

tethering the broad curving flow so sweeps

back its outer edge drawn in while the inner

slips into a concave depth bending

around itself and down

a twisting axis

to a point

searching expense

in sway; or,

B. when from force coursing through volumes

flumes a counter; a countering shove,

the rent heavy in tumult, tethers

across the seam and drawing counter,

a chopping across, against its own tumble

plunging shallowly down and

backing out into a hung up,

softly lapping slack.

2. a cultural countering press

or static slack.

___ ___ ___

Daniel assigns his friend Lohren Green's book, Poetical Dictionary (click to buy off amazon

Also, things keep bubbling up and pushing me. I'm banking on shucking those tethers, though, as the year flies by and I start packing boxes; there's another pool to wade in ahead.

___ ___ ___

Have you noticed how many bloggers have nodded towards Eloge de l'amour recently? There's something in that ether-net. I've kept my Netflix disc at home for over a month. I can't let go. Fitting. Here's some sites similar, but different, from a some thing (that I will mail tomorrow) about gulls and ghosts, presence and absence, making the flight of digital a tangible reality where all kinds of happenings tug and pummel one another, where the concave bends itself across the seam.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

10:10 PM

1 grooves

![]()

Labels: images, liquids, Lohren Green, Mamoru Oshii, poem, rwk, screenshot, words

Monday, September 08, 2008

Found Facts. June 2008.

by Ryland Walker Knight

[I could probably make this a higher quality file but it's such an abject little thing as it is that, hell, it doesn't need any modicum of sheen. That might be dishonest. So, this is offered with humility and a little embarrassment on behalf of everybody. Although, to be fair, we all know who the star is...]

Telluride #3: The image is alive. Waltz With Bashir.

by Ryland Walker Knight

[Waltz With Bashir had its North American premiere at the Telluride Film Festival. It was the first official screening we in the symposium attended. As can be expected around these parts, lots of life happened in the week and a half between that viewing and this posting. Sony Pictures Classics has bought the film and will distribute it beginning in December after its festival run concludes. It's certain to be brought up again as more people see it; the opportunities will present themselves soon enough. Until then...]

Amber flares shower past high rise hotels on the beach of Beirut and youthful Ari Folman floats naked off the shore, ignorant and immobile. Two fellow Israeli soldiers wade to the foreground and Folman stands up to follow them ashore in silhouette where they dress in fatigues, their pliant limbs cut against the golden night skyline. In the streets at dawn, Folman turns a corner into a wave of women clad in black burkas wailing; as the cavalcade of cries pass the stationary soldiers, Folman stands fork, impassive. Survivors of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, these wives and sisters flood the frame aimless and wretched, crowding Folman. Twenty-four years later, the grown man Folman cannot remember where he was during the massacre despite being stationed somewhat close to the bloodshed. In fact, he hasn't thought of it in ages. But after hearing his friend describe a dream about rabid dogs, and its links to the Lebanese Civil War where he shot canines not people, Folman has this dream about water and flares and the hurt of it all without specifics. To counter as much as to document this plaintive and guilty resonance, he makes a film. Encouraged that investigation produces understanding, even if such a project forges intuitive links that proffer more questions in lieu of definite answers, Folman starts to draw out his past. Waltz With Bashir is that labor of and for understanding.

The film opens in that dream about dogs: racing through a city, plowing through cafes and intersections, their snarls wet and fierce, seeking the dreamer, Boaz Rein Buskila, ragged. Not rotoscoped like Linklater and not as ugly as an Aqua Teen bit, the flash animation juts and floats in delicious washes of color. The dogs don't quite run but glide, the rain doesn't quite fall but simply slant, tables jerk upend and bodies skid aside; nothing is "real." Indeed, the real is the question. Bashir is organized around series of interviews that yield memories recounted as dreams, including one that explicitly goes into the dream world. Carmi Cna'an opens his war story, perhaps the most gorgeous sequence in the film where darkness pervades the frame, on a boat, where nerves get the better of him and, after vomiting, he lays down to escape: "When I'm scared I fall asleep and hallucinate." He dreams a giant, naked, blue woman boards the now-teal boat to save him; she brings him into the water where he lays between her legs looking back at the yacht, which promptly explodes a blood red. Another interviewee, Roni Dayag, tells a story about water: after an ambush, he flees to the coast to wait for dark; under nightfall he slips into the ocean and swims countless miles south in retreat, occasionally dipping under the surface to avoid helicopters' spotlights and armory, only to find the unit he thought abandoned him (and that he thought he abandoned). Folman's best friend, Ori Sivan, tells us what we know later: water is associated with guilt and fear, a fake haven from the blood on shore, that Ari's recurring dream (however material and palpable) is a projection. Thus, this Waltz is a reckoning, a search to account for Ari's intentionality, how his mind (which ours becomes in the film) has failed to be and is directed anew towards this terrible lacuna.

The film opens in that dream about dogs: racing through a city, plowing through cafes and intersections, their snarls wet and fierce, seeking the dreamer, Boaz Rein Buskila, ragged. Not rotoscoped like Linklater and not as ugly as an Aqua Teen bit, the flash animation juts and floats in delicious washes of color. The dogs don't quite run but glide, the rain doesn't quite fall but simply slant, tables jerk upend and bodies skid aside; nothing is "real." Indeed, the real is the question. Bashir is organized around series of interviews that yield memories recounted as dreams, including one that explicitly goes into the dream world. Carmi Cna'an opens his war story, perhaps the most gorgeous sequence in the film where darkness pervades the frame, on a boat, where nerves get the better of him and, after vomiting, he lays down to escape: "When I'm scared I fall asleep and hallucinate." He dreams a giant, naked, blue woman boards the now-teal boat to save him; she brings him into the water where he lays between her legs looking back at the yacht, which promptly explodes a blood red. Another interviewee, Roni Dayag, tells a story about water: after an ambush, he flees to the coast to wait for dark; under nightfall he slips into the ocean and swims countless miles south in retreat, occasionally dipping under the surface to avoid helicopters' spotlights and armory, only to find the unit he thought abandoned him (and that he thought he abandoned). Folman's best friend, Ori Sivan, tells us what we know later: water is associated with guilt and fear, a fake haven from the blood on shore, that Ari's recurring dream (however material and palpable) is a projection. Thus, this Waltz is a reckoning, a search to account for Ari's intentionality, how his mind (which ours becomes in the film) has failed to be and is directed anew towards this terrible lacuna.Ari understands he will never erase his (or Israel's) complicity, but if he can flesh out the picture, he can provide a voice to their limitedness that asks forgiveness without assuming endline benediction. The spike of the final five minutes reasserts that: after an animated zoom into Ari's face, standing at the edge of the Sabra and Shatila camps, watching another wave of wailers, the image breaks form into video coverage from 1982. Not quite a Kiarostami coda, but certainly effective, we see these women cry along with the image; the digital bleeds, combing the bodies massed in corners or piled in the thoroughfare, the trace immediately ephemeral, the world as a glitch. It's unmistakable -- this happened and you can't hide from it. But the animation isn't papering over guilt that the video unveils. It's a direct mediation, an admission that we mediate our memories, that memory may be matter but its image is metabolized over time.

Ari shows Roni a picture of himself from 1982: "Do you recognize me there?" Roni, always blank, offers, "No." Ari says, "Me neither." Roni begins his story and we see a tank troop set a camera on the canon, pointed back at the quartet; right before the picture clicks, the camera falls off that arm of destruction out of frame. The camera fails, lies even. This is not representation. Film is creation, making material. Unfortunately, this brilliant, subtle moment is trumped by a much larger explication of the same in a protracted monologue by a psychiatrist Ari visits who tells a story about another veteran who dealt with being in the war by pretending he was filming, pretending he was behind a camera; until the camera broke and his mind with it. However, Bashir does not suffer too heavily under this or other instances of literal interpretation. Its queries about documents and film documentary, about how we seek absolution and catharsis, about the ethics of the image -- all stimulate imagination and investigation rather than shut it down simple and closed. The film exists in tension with all this evidence, pushing its material, its memories (at one point across the globe and back in time from the Netherlands of now to that West Bank of then) past general dread into singular horror. If anything, at bottom this Waltz against death reminds that the image (memory, understanding, light) is alive and deserves (demands) our accountability at all events.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

9:43 AM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: animation, Ari Folman, criticism, ethics, images, memory, rwk, Telluride 2008