Notes for the Day: Spring Break is Here

by Ryland Walker Knight

Open your eyes, your ears, your nostrils: the weight is over.

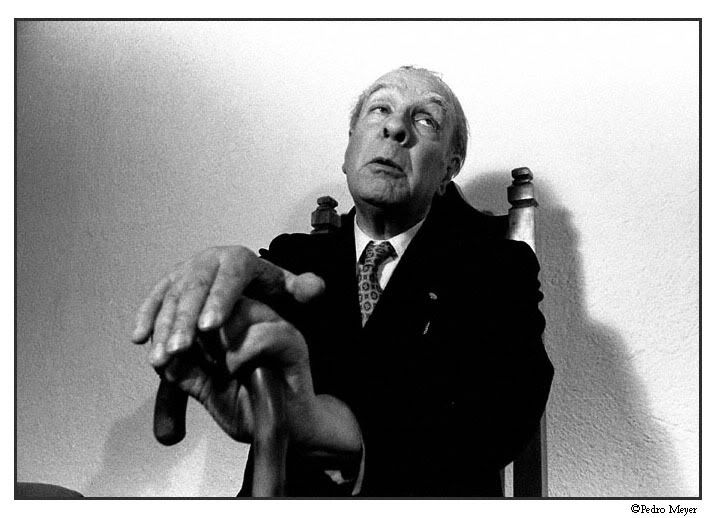

It would be an exaggeration to say our relationship is hostile — I live, I allow myself to live, so that Borges can spin out his literature, and that literature is my justification. I willingly admit that he has written a number of sound pages, but those pages will not save me, perhaps because the good in them no longer belongs to any individual, not even to that other man, but rather to language itself, or to tradition.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:00 AM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, rwk, screenshot, Wong Kar Wai, Ziyi Zhang

[Just cause it needs it, even if it's a jagged jumble. Just cause I gotta sing. More later, but for now here's an email I just wrote, edited only slightly.]

From: Ryland Knight

To: Keith Uhlich, Ed Gonzalez

Subject: battle in heaven

I just watched it a second time.

You ever get that feeling, after seeing true beauty, that you don't want to write anything down because it will, somehow, kill that beauty -- render it immobile and pointed, cemented in place? Of course, there's the opposite impulse fighting up inside as well: I need to speak it, sing it out loud! This is it! Look right here, I beg! But even that celebration does it an injustice. There's too many things to sing all at once. How perfect the key piece of music (in this movie) is a fugue! Life is a fugue, filling in, coloring and layering time and loves and fears and deaths and cars and musics and footballs and cocks and pussies and breasts and bloods and crosses and feet and mountains and antennae and glasses and knives and jackets and cities and mud in some eternal return of present tense living.

Yet, the film isn't perfect or anything and it's hardly enjoyable in any kind of "traditional" way. But there's something so crystal clear in its construction and execution that, as with any great film (any great art!), of recent or earlier vintage, you feel the world has substance. We aren't aimless. We are living and, while it can be scary and ugly, this is a great world to inhabit -- a great life.

Writing on this is already tough and gorgeous but I will do my best. Soon. But I probably should have waited on watching it until I was done with my Borges essay for Monday. Maybe if I get this out of my system and stick it down in words I can find a way to shift my brain back to Borges & I.

I can't wait to see Japon.

Eyes open, fists up, spirit wide,

Ryland

PS - 2006 was a fucking tight year for movies.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

12:10 AM

9

grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, blogging, Carlos Reygadas, difficulty, letters, rwk

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but of the clay is vile

Benearth our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

by Paul Laurence Dunbar - 1896

by Ryland Walker Knight

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

12:30 PM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, movie magic, rwk, Truffaut

by Ryland Walker Knight For a long time I thought I didn’t get Antonioni.

For a long time I thought I didn’t get Antonioni.

[To read the rest of the article, click here, and you will be redirected to The House Next Door.]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

2:00 PM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: Antonioni, appreciation, list, movie magic, rwk, The House