Susana: Buñuel at Play

by Steven Boone

Luis Buñuel's Susana (1951) might be his worst, most entertaining film. After shooting his low-budget masterpiece, Los Olvidados in 1950, Buñuel was on rocky terms with Mexican audiences. That film represented Mexico as a nightmare in which failed social services and a hostile or indifferent economy resulted in children tossed aside like trash. Bunuel's producer, Oscar Dancigers, had agreed to let the aging surrealist make one personal film for every two commercial ones. Buñuel had delivered, with two crowd-pleasers, the musical Gran Casino (1946) and the screwball comedy The Great Madcap (1949). But the hostility toward Los Olvidados ended Danciger's and Buñuel's scheme just when it really got going. The director made Susana for another producer, Sergio Kogan. (The ironic postscript is that Los Olvidados went on to win the Palme d'Or at Cannes before its release to worldwide acclaim in 1952.)

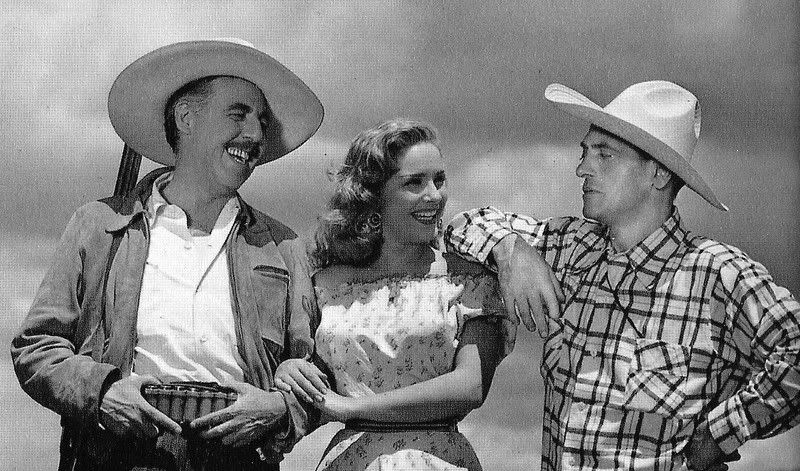

With Susana, Buñuel honed an elegant "invisible" storytelling style that would reach perfection in Viridiana. This might account for the overacting and bombastic musical score: Maybe Buñuel was so caught up with camera choreography (on a tight 20-day schedule) that he let the performances run amok. Seen today, the bombast works as camp. It kind of fits this (literally) stormy melodrama about a female juvenile delinquent (Rosita Quintana) who single-handedly wrecks a wealthy Mexican rancher's home by seducing him, his son and his most trusted ranchero. Fernando Soler (who brings the most subtlety of the entire cast) plays the rancher as a tough-minded middle aged jefe who Susana reduces to a fool in love.

Buñuel uses the horny premise to indulge his leg fetish and favorite sacreligious themes. Buxom, hot-blooded Susana prays to the "God of prisons" to bust her out of juvie-- and He does. She escapes to don Guadalupe's ranch and proceeds to eat every man in sight. If you watch Susana without sound, it's as feverish and irrational as something like L'age d'Or. Buñuel's camera gets away with sensuality and eroticism less visually adroit directors wouldn't know how to manage.

Here's a sample of that craftiness, set to David Axelrod's song A Divine Image:

[Editor's Note: This is a belated submission to the Luis Buñuel blog-a-thon (hosted by Flickhead) that ran last week. I was planning on seeing Los Olvidados to contribute a tandem piece with Steve's delightful little appreciation, here, but life got in the way. So, if you want more on Buñuel from me, you'll have to wait. Luckily, thanks to a special gift from Senor Boone, I will be able to watch a lot of the Mexican films sooner than later. So stay tuned. -- RWK]