Round sound and stopped clocks. Stellet Licht sees sun spots.

by Ryland Walker Knight

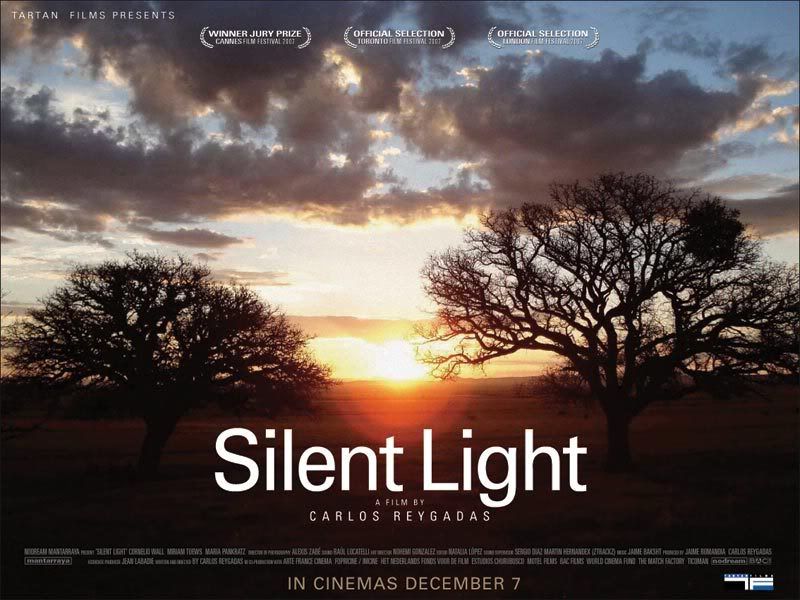

While Carlos Reygadas' first two pictures are without a doubt more immediately impressive (to say more shocking) than his third film, neither Japòn nor Battle in Heaven have anything on Stellet Licht when it comes to ebullient photography. For all the flashy formalism, though, Reygadas has made a quieter, more tender film than before because of this picture's remediation (evolution?) of his signature aesthetic preoccupations. If Battle in Heaven shuttered the broken wall country vistas of Japòn in Mexico City’s urban myopia, Stellet Licht nearly strips the world of material frameworks: here, the glass of windows (and of the camera lens), coupled with the light of the sun, and its splayed presence (or its dark absence), are enough for Reygadas to round the pleated space of his films (of the spirit). Sure, frank sex still plays a part. But those unabashed lens flares, as well as the film’s impeccable and complex sound design, background Reygadas’ concerns with the messiness of sex and desire to foreground the relative purity of, and paramount confusion between, love and faith. Perhaps it’s Stellet Licht’s gentility that shocks most of all.

The film opens gentle enough with a protracted time-lapse dawn accompanied by sounds of the world awakening. Yes, Genesis. The single-take sunrise is gorgeous, to be sure, but the exaggerated sounds (as in a Bresson offering) frame the film as much as the light of a new day: animals bleat, wind whips, and, once indoors at a breakfast table silent with prayer, a clock ticks. The prayer lasts long enough for Reygadas to introduce us to patriarch Johan, his wife Esther, and their stable of six children, in perfect compositions that isolate the parents and group the children. After a mostly-silent breakfast, and a reminder “I love you” goodbye, Esther and the children leave Johan alone, at the end of the table, in the middle of the image, directly underneath that won't-quit clock. Johan sits quiet, staring at a spoon. Then he stands, retrieves a footstool, and steps up to stop the clock. Sitting again in the still of the room, the camera pushes in closer, and Johan cries.

The story is simple: Johan has fallen in love with another woman, Marianne. The complication is Johan still loves Esther, and he has been completely open about his affair from the beginning. This proves too much for Esther’s heart to bear, naturally, but the amazing thing about Reygadas’ film is its lack of judgment. There’s no scolding. Or, even when there is a scold, it’s undercut by empathy a second later.

I am told the great act of humility that closes Stellet Licht owes a debt to Dreyer’s Ordet, which I have not seen (nor have I seen any of his films, for that matter). Some critics have used this against the picture; others do not. I imagine Reygadas is smart enough that as much as he may inherit from Dreyer, his vision of the scene is singular. For instance, I doubt the Swedish film uses Jacques Brel as a touchstone for humble, beautiful, sexy gallantry. The inclusion of Brel’s 1967 performance of “Les Bonbons” (look below), viewed in a van with the doors closed, says as much about the gentle spirit of Stellet Licht and its characters, as does the supposed Dreyer quote. For one, it’s a song, a combination of storytelling and music. For another, it’s a filmed version of the song, introduced first on a television, then, bookended by fades up from and down into black, reprised across the full widescreen as a cropped television image. In a film about a remote group of Mennonites (a Christian Anabaptist denomination that resists pictorial representations) in Northern Mexico, this minor movie watching is an immanently suspect activity for its characters. But if Johan is testing his faith by falling in love with Marianne, what should stop him from pushing the boundaries of his faith with music videos, as he loves music, too. Earlier in the film we see Johan at his most excited singing along to a song on the radio, circling the camera, and his best friend, in his truck, in a patented Reygadas 360 (or a dizzying 1080 as it is here). Perhaps the overriding thematic question thus far in Reygadas’ films is “Where and how do love and faith intersect and interact?” The hilariously baffling thing about his films is that Reygadas wants to answer that question with every single shot he composes: he sees the beauty in everything.

Filmbrain’s mid-essay assertion points towards how I find myself drawn to these three marvels Reygadas has provided us with, as it speaks to certain filmic obsessions I harbor:

As with his other films, Stellet Licht’s tremendous power comes not from its narrative, but from Reygadas’ aesthetics; a masterful, poetic blending of son et image. The film exists at the intersection of John Ford and Terrence Malick, what with its epic landscapes, use of shadow, and depiction of nature and the elements as almost sentient beings.It’s this regard for the “real matter” of the natural world, in tandem with his generosity towards his characters, that makes Reygadas’ films so special. You’re as likely to see a close up of a dog, or an orchid, or catch an umbrella flying through the corner of the frame, as you are likely to encounter a human face (or other body parts of humans, for that matter) front and center. In that regard, it’s easy to identify why finding Apichatpong Weerasethakul, along with Reygadas, this year has meant so much to me as a viewer, and a thinker. Their brand of what I want to call philosophy in film is one born not simply of humanistic striving for transcendence (although you can see that struggle in both filmmakers’ oeuvres thus far), but from how humans live in a world filled with things that are not human—spiritual or material, aural or visual, it makes no difference. So when Johan’s father starts the clock again at the close of Stellet Licht, it signals a choice of how to live in such a world. Ignoring the world doesn’t work. Faith and love are about respectful, thoughtful attention—to the world, to the spirit, to the life lead here on earth under the sun and stars among all cries of pain and delight heard across all time, clock or no clock.

[Final Notes: I wish I could have shown you more from the film but this will have to do. Also, I saw the picture at the Yerba Beuna Center for the Arts Screening Room on Sunday night and the projection was a little wonky, which made it a little harder to gauge certain scenes, as Reygadas plays with focal points in this picture in distinct way. So, as nice as it was nice to see in a theatre, I look forward to my DVD copy so I can play with screenshots and revisit all I missed. Even this post didn't get to talking in earnest about all that goes on in this. I promise that one day down the line I'll get into it real serious with his films. (Still learning, always learning, right?) Until then, can't wait for the next one, Carlos!]

From Dan Salitt's Toronto coverage at Senses of Cinema:

ReplyDelete2007’s crop of competition films at Cannes was widely considered the strongest in years. Mexican director Carlos Reygadas’ Stellet licht (Silent Light) is one of the acclaimed Cannes titles that has already received extensive coverage – and yet commentators have had difficulty finding a conceptual framework to integrate such hot-button aspects as its conspicuous borrowings from Dreyer's Ordet (1955), not to mention the seemingly self-sufficient virtuoso tableaux that begin and end the film. It's becoming increasingly clear that Reygadas skews more postmodernist than modernist, and perhaps his suggestions of a unified aesthetic enterprise (like the clock that is stopped early in the film and started again after the climax) are red herrings. The extraordinary physicality of his camera style, and his fascination with large-scale systems (natural, organic and mechanical), serve largely to defamiliarise the world; and his visuals can be seen as an attempt to remove camera movements and compositions from their traditional interpretive role, and to invest them with a weight and a physics that renders them autonomous.

I wish that references to the Dreyer film (You've never seen ANY, Ryland? Get thee to Passion of Joan of Arc at the PFA next calendar!) weren't so obligatory to be mentioned by practically everyone who writes on this film. I don't usually read reviews of films I already know I want to see, so I hadn't been reading about this one, but still inevitably kept hearing Ordet Ordet Ordet, and consequently I was able to predict the film's two most notable events well before they occurred. Maybe it's terribly shallow to care about so-called 'spoilers' for a poetic film like this one (is a Shakespeare sonnet 'spoiled' by hearing the volta quoted out of context?). Reygadas has created something to appreciate outside the context of narrative expectation, and perhaps it's somehow 'purer' to experience the film that way, but I could have done that the second time through. I feel a bit robbed.

ReplyDeleteMentioning Ordet in a review for this film is akin to mentioning the Crying Game in a review of a film whose plot hinges on someone hiding their true gender. Or perhaps mentioning Au Hazard Balthazar in a review of a movie structured around a surprise appearance by a donkey. But since everyone else has mentioned it by now, a review of Silent Light that DOESN'T contend with Dreyer somehow seems incomplete... Frustrating.

Hopefully I can get over this annoyance; it's not a problem with Reygadas or the film itself, which is clearly something special. Not since Signs have I seen a film that so directly takes on the question of what it means for a director to be God of his constructed universe...

Yeah, Ry, you gotta see Passion of Joan of Arc, either at the PFA or the excellent Criterion disc.

ReplyDelete온라인카지노 I found this to be interesting. Exciting to read your honest thought.

ReplyDelete토토사이트 We stumbled over here from a different web address and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to looking into your web page repeatedly.

ReplyDelete토토사이트 I recently found many useful information in your website especially this blog page. Among the lots of comments on your articles. Thanks for sharing

ReplyDelete