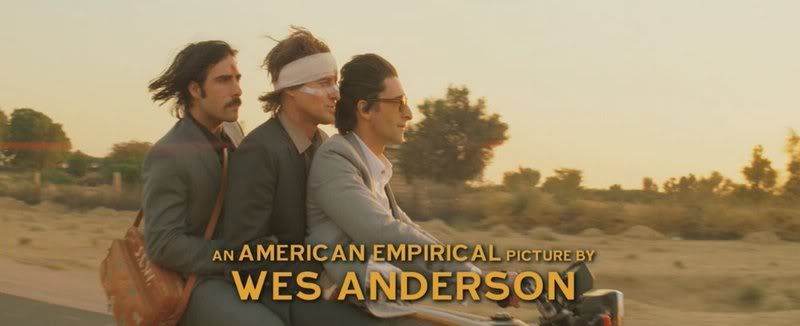

____________________[Editor's Note: This is a slightly-edited email conversation between Steven Boone and Ryland Walker Knight. Clearly a lot was discussed. But as descendants of another Whitman, we contain multitudes, much like this film, and there was plenty more to talk about. But two call-and-responses seemed like a good enough jump off. Please help us continue the conversation in the comments. As Steve says, it's kind of sloppy but it's cool. It's good enough for now.]

____________________

____________________Ry,

“We're all sensitive people/with so much to give.” Marvin Gaye may have been singing that just to get into a girl's drawers, but those two phrases also inadvertently define the great film directors: Sensitivity and generosity. It takes an audience of similar temperament to get into their films.

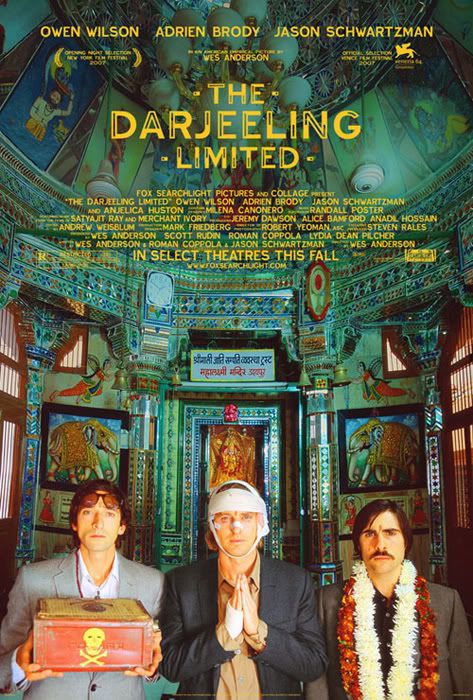

Wes Anderson is one of the greats.

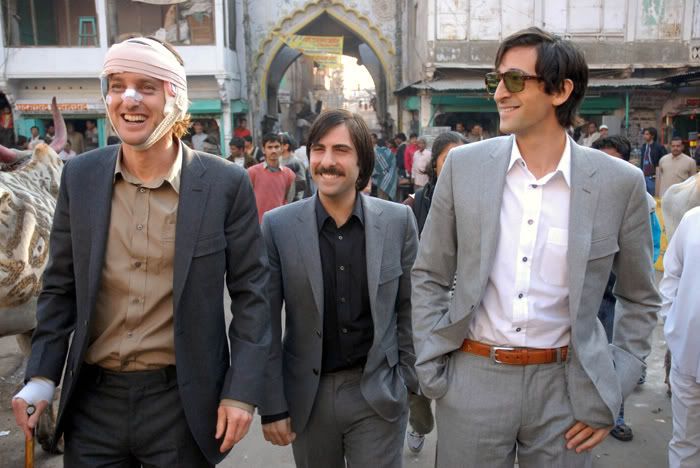

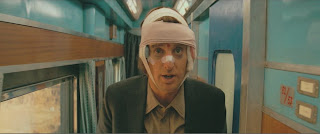

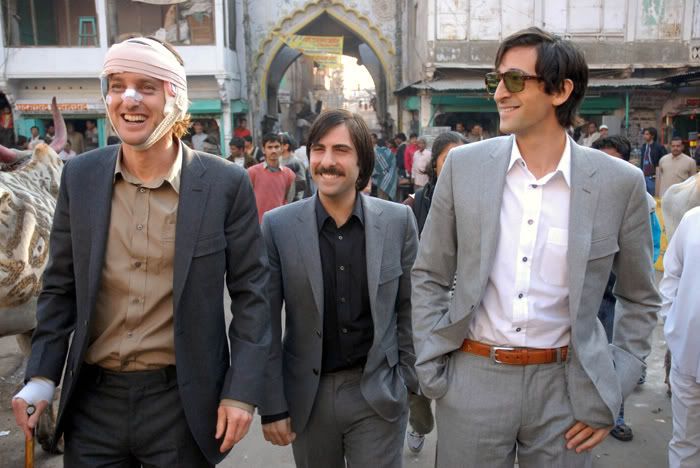

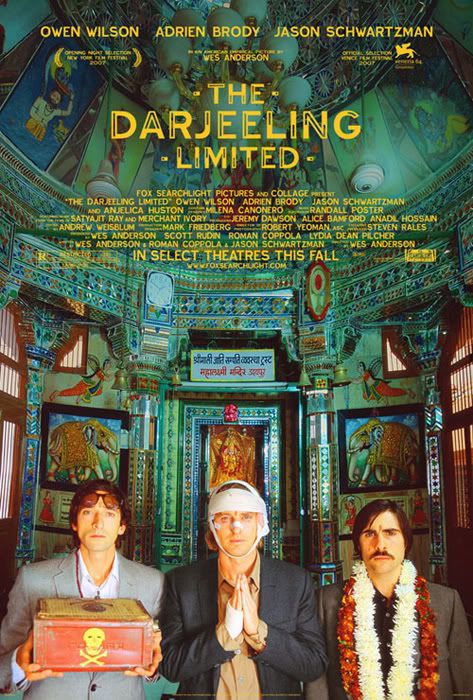

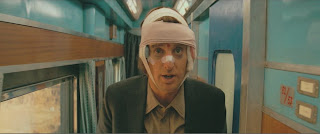

I had punkass tears leaking out of my eyes from the moment Owen Wilson stood up and said the first thing he thought about when he came to (after a near-death experience) was his brothers, and they all hugged a little awkwardly. Why is this moment so great, or special? We've seen brothers bonding like this in 10,000 other flicks. Actually, looking back at my description of it, it sounds like some TV movie shit. What sells it (other than Anderson's (or maybe Jason Schwartzman's or Roman Coppola's) dialogue writing, which lays out torturous, hilarious roadblocks of cynicism and petty grievances on the path to true understanding) is Anderson's camera eye. (That's the other thing that makes a great director: Gotta know what shots and cuts can really do.) Owen declares his love to his brothers in a kind of wobbly, sloppy shot taken from a long lens way down the train car. In a film of rock-solid compositions and tense pinpong cutting, this image is a fuzzy anomaly. It's like a little kid scribbling “I Luv Yoo” in crayon on his daddy's manuscript. Even if Wes Anderson is an asshole in real life, shots like that one assure me there's something better buried in his soul.

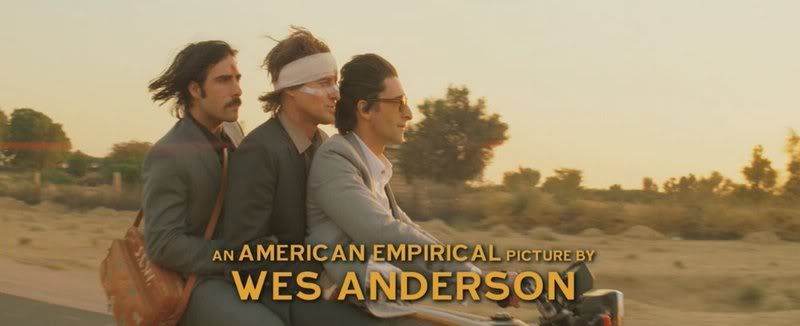

The camera is everything. Anderson knows that his selection of lenses and camera movements are as critical to conveying his wiseass charm and humanist worldview as his casting, dialogue, music and production design. (Those latter four are what most critics choose to fixate upon.) Like, why does he use lateral dolly shots to do the job normally left for pans? Because they bear a certain weight that offsets the loopy/mopey, boyish/world-weary comedic atmosphere in his compositions. These shots have their soul mates in the hollow, heartbroken eyes of his three male leads.

All of this to conjure up a miracle: A big, splashy widescreen film about three obnoxious rich shits... that made me, a working stiff, feel for them. Let's face it: Wes makes movies about spoiled rich kids, about white adults suffering abrasions to their sense of entitlement. I love

Bottle Rocket and

Rushmore, but the sense of elitist angst and preciousness in

The Royal Tenenbaums and

The Life Aquatic pushed me away in their first acts.

Darjeeling reached out to me. It was a personal breakthrough because I arrived at the simple understanding that nobody can help what they were born into; essence is everything. These little snotty punks are used to being waited on and catered to, but they are not bad people. Yes, there are sociopaths, tyrants and American psychos out in the world, but there are so many more decent folk wearing an asshole's uniform only for survival's sake.

There's too much to share about this movie. Any conversation we have about it is doomed to be random and sloppy. Cool.

--Steve

____________________

____________________My fellow fun-lover,

"The camera is everything." Perhaps nothing else needs to be said to understand the joy of this film. Still a prop in

The Life Aquatic, and working more as a detached omniscience than as a personality in the three films prior, the camera in Wes Anderson films has always been conspicuous, and distinctive; but in

The Darjeeling Limited it becomes a member of the cast as much as instrument of the crew. More specifically, the camera is a (non-) member of the trinity of brothers. Each of the brothers addresses the camera, and by consequence the audience. The camera takes a spot among the lineup of the brothers when they are seen from behind: two brothers to the left, one to the right, with a spot just off-center for the camera to push in among the fraternity. Reverse shots of the brothers eclipse this space, placing the three side-by-side without the gap, but the visual discontinuity makes sense, oddly, because Wes Anderson's camera is not here to document: it is here to make pretty pictures to tell a sometimes-silly, sometimes-somber story from a perspective that marries the know-it-all style of his earlier films with the on-the-edge style of

The Life Aquatic. Surrendering to this hilarious tension of contrivance is, perhaps (again), the first step to enjoying

The Darjeeling Limited, or any movie Wes has made (or may make).

What I find most frustrating reading negative reviews of the picture is that each writer of such essays seems determined

not to enjoy him or herself. Which is not to say I prize an essay where it's all about the writer and his or her reaction to the film. Rather, I wish more writers spent a little more time reflecting upon their reactions in as generous a manner as possible. Suppose there might be a reason, within the rubric of the film, that Wes Anderson choses to shoot scenes the way he does. Where the hell is this odd, almost-fish-eyed camera? Is it a point-of-view? Is it not? What's with all the tacky zooms? Why is the camera moving laterally, or panning 180, or 360, degrees? Why all this slow-motion? Why is the camera everything? The easiest answer to that summation-question would be: the camera is not a tool, really, for Wes Anderson, but another set of eyes. What complicates this notion is how we in the audience are continually confronted in

Darjeeling by the eyes of the characters: the camera becomes not just another set of Wes-eys but, at the same time, audience-eyes. You there in your seat -- yeah, you -- you're here, too, onscreen (and in the page) -- you are at once audience member, brother, absent father, absent mother, a businessman, a girlfriend, a wife, a steward, a man-eating tiger. And, to echo something I've written before, they are all happening, always (and already).

This is why I find myself welling up: it's beautiful, this present tense. To invoke the present tense is a little redundant, I know, given we don't necessarily live in the past (though we carry it) or the future (though we reach for it) right here and now. However, all those slow-motion shots are the elongated present, a delicious unveiling of (almost) every detail of right here and now, of every plane of activity. (Maybe, in as general a sense as possible, that's simply what movies are?) And what happens at the end of one of these slo-mo scenes?! We match-cut back in time! All because of a look! (These exclamation points are to signify my delight that something as simple as looking at your brother can spur a story. And to make this paragraph as silly as it needs to be to get you to care about what I felt while looking at the movie.)

Adrien Brody's look across Jason Schwartzman at Owen Wilson (as brothers Peter, Jack and Francis Whitman) triggers a memory, which is a mini-movie unto itself, wrapped up inside the bigger, whole movie. We know from earlier in the film that this memory also serves as material for a short story Schwartzman's Jack has written, and shown to Peter, about the day of their father's funeral. Later, Jack will read to his brothers the ending of a new short story he has begun writing, without knowing the beginning; the lines of dialogue are direct quotes from

Darjeeling's companion "Part 1" film,

Hotel Chevalier. Jack insists throughout that all his characters are fictional until this moment, when he accepts his brother's compliment (Peter says he likes how mean Jack is in the story), which is more validation than if they simply said it was well written, as Francis does earlier.

I think the best “commercial” review of the picture thus far has been from

Glenn Kenny, of Premiere. His last two grafs seem apt here:

This movie is as much, if not more, about the construction of fictions as it is about its ostensible plot. Wilson's Francis, trying to put his life back together after a suicide attempt, constructs the India trip, with its laminated itineraries, as a potential happy ending to his family saga. Brody's Peter seeks a continuance of the narrative of his late father (the last time the brothers all saw each other was at his funeral) by furtively, obsessively, hanging on to the patriarch's old possessions. Schwartzman's Jack is a writer of short stories — stories he insists are "entirely fictional." Much of the film's subtext is devoted to both peeling away and reinforcing that claim.

But The Darjeeling Limited is as much about fiction as it is about family. That it succeeds so well and so slyly even while dealing with these topics in its own stylish but unsparing way is reason for moviegoers to rejoice.

Of course, this quote echoes a few things for me, including my own dealings with Wes Anderson's beguiling, and delightful, films. I think you can make this argument about storytelling with any of his films: it is as major a theme as family or death or theatricality are for Anderson. Think of Dignan's fiction about Mr. Henry, and vice-versa. Or Max Fischer's dad-as-doctor lie. Or all the books in

The Royal Tenenbaums. Or, hell, all of

The Life Aquatic and its constant movie set setting. Think of his TV ads. Think of how Schwartzman prepares his room for Natalie Portman's entrance in

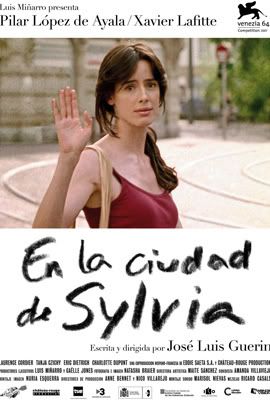

Hotel Chevalier. The effectiveness of these offerings, while propelled more by dialogue than visuals the earlier you go in his filmography, is tied, at least partially, into how Anderson uses his camera. He's not making a representation of a world -- he makes the world as he would have it,

as a movie. (No d'uh, right?) Complaints about his films as contrived are as wrong-headed as can be: to invent a fiction,

in any medium, is a contrivance, an artifice from the get-go. To tether it to some kind of “reality” is a limitation not of scope or imagination (that's tough work to make "real" humanist stories) but of understanding.

(This is similar to what makes Werner Herzog so interesting: he does not delineate between "fiction" and "non-fiction" films. He simply makes films. He understands that even a "documentary" is a fiction. It has its own rules, sure, but the documentary in Herzog's hands is not about actually documenting the events. In

The White Diamond, maybe his greatest film, he does not show the balloon when it is first dubbed such, he lets a man sitting on an inflatable chair smoking a joint call it a “white diamond.” A lesser filmmaker would have cut immediately to the balloon. Herzog simply holds on the man as he soaks in the scene. The fiction of the object is as important as the object itself.)

For Wes Anderson, he makes sure his films are fake-ish (or overtly self-reflexive) by, among other things, stuffing them with these details and whip-pans and sudden narrative tangents. He does not write three-act structures. He writes happenings, constant happenings, constant unravelings. Things don't add up as they would in a “traditional narrative.” Things just keep happening. They go left, they go right, they go up the mountain (via a staircase?), their train gets lost, there is a death, there is another train, the movie starts over again.

I saw the movie two times in as many days and I could see it again right now. In lieu, may the sun shine bright on us all. Let's get into it!

later, ryland.

____________________

____________________Ry,

No, the camera's not the whole show, but the objects and Anderson's dollhouse placement of them are largely about "subjectivity" as well. Critics have already sucked their teeth at the literal "baggage" that trails the brothers everywhere they go. Well, the obviousness that they're so up in arms about is what fleshes these characters out. The props and bric-a-brac convey plot/character/backstory nuggets (like Bill Murray's family portrait in

Rushmore) not just for efficiency's sake. They trouble and redirect some of our less charitable tendencies. Wes has a crucial understanding about people: We size each other up, from head to toe, mercilessly. We make instant judgments. Ry, you mention that he makes his own worlds. Yes, and in his worlds, people are exactly what they wear, eat, carry or cast off. It's plain to see who's up to what in Wesworld, even though the characters are mostly flying blind as if they're in our prismatic, deceitful world. (And, of course, psychologically, they are.) Owen's bandages, Schwartzman's cheesy ‘stache and Brody's shades tell us up front what these guys are dealing with. Their journey in the film is toward seeing each other the way Anderson presents them to us -- as lost boys.

Oh, brother, right? I don't know too many people who would put up with such preciousness. I'm picturing

Darjeeling playing on Comedy Central in the day room at Rikers Island a few years from now. Not much of a draw. But on the big, wide screen, this movie smashes prejudices against creampuff elites by the sheer force of gravity (the mise-en-scene) and inertia (the camera movement). In real life you can probably knock these dudes over with a light shove (well, probably not Brody) but Anderson's compositions ain't laying down for nobody. They are imposing, and yet nimble and feathery as needed. Athletes train forever to get this combination of power and grace.

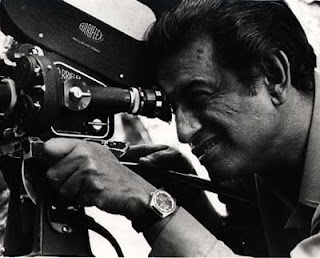

Which brings me to

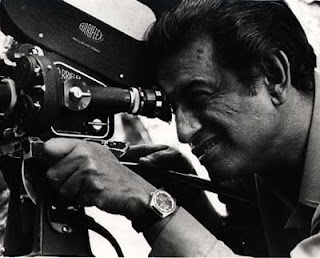

Satyajit Ray. You haven't seen too much (or any?) of his stuff, and it is absolutely not necessary for blissing out on this flick. But having watched Ray's

Apu trilogy as many times as you are bound to see

Darjeeling, I can say that Ray is Mr. Power and Grace. Anderson pays him tribute throughout this film, mostly by using film music composed by Ray and Ravi Shankar. However, the scene where the brothers take a whiff of the perfume and the joke about trains in the distance will both become even prettier when you see how affectionately they bow to Ray. I can't wait to send you these

Apu films, along with his

Devi, from 1960. I'm in the middle of that one right now, and it has all the rapture of that overhead baby shot in

Darjeeling--arguably--no, no argument here: In-damn-disputably the most wondrous shot of an infant ever presented in a film. Those feet in the margins of the frame.

But that's all side stuff. The real fun of looking back on

Darjeeling is how Anderson cleared that tightrope of silliness, reflexivity, grave seriousness and irony without a sweat. Let's get into that.

--Steve

____________________

____________________My man,

During our exchange I was directed to

Carina Chocano's positive review of

Darjeeling, which opens with a remarkably smart paragraph that summarizes some of the problems of the criticism of Wes Anderson and echoes some of what you were getting into at the start of your last missive:

It's hard to approach a new film by Wes Anderson without feeling like you've walked into an argument. There's something about his dollhouse aesthetic, his storybook formality, his miniaturist's attention to detail and his dogged belief in the power of objects to elicit the most oblique and recondite emotions that seriously sets people off. Why is a question for another paragraph, but needless to say it's exactly this staunch commitment to artificiality that makes his work what it is.

In addition to the surface-as-essence approach to dressing characters and scenes in Wesworld, there's something about how that subjective camera shoots those objects that imbues them with character. How things are arranged, perhaps staged, to echo myself again, matters, because this new film, like all his others, is still “cluttered” with detail, for all its acclaimed “maturity” (from its supporters). How the details accrue in the picture is probably a good indicator of how Wes “clears the tightrope” of storytelling. As a practice, storytelling relies on affective details that trigger a response. If we can agree that art is about life, why shouldn't something this artful (and artificial) be as resonant as a piece of art that is artful in its artlessness? Is it just a matter of taste at that point? To argue aesthetics seems a silly dead end, especially since I don't know much about it outside thinking, “Well, that sure is pretty and it looks like it was a thoughtful choice -- on the part of the artist and consistent with the rest of the work of art.” Plus, “aesthetics” is such a broad topic to whittle down to film style. We can table that. What I'm curious about is why Wes Anderson's rhetoric ticks people off. Because I can eat it all day. His world is full of things. Even in slow motion the world is alive with motion and speed.

The idea that objects (including people) can "elicit the most oblique and recondite emotions" in and of themselves and their appearance should be a delight, not something to harp on: it is an offering. Walking out of the film on Friday my friend said, “I feel like I've been given a thoughtful gift.” I think this kind of reaction is what Wes is aiming for in how he shoots objects with his camera. The objects carry history that can produce associations. Opening this film with Bill Murray's Businessman missing the train in slow motion, while a young man, Adrian Brody's Peter, runs past him, is not meant as an inciting incident in some kind of narrative but simply to trigger a response and tell you how things are arranged in this movie (this world): it's all about the train. The train is the name of the movie. The train

is the movie. So when Bill Murray can't catch the train, Anderson is showing you, in as simple terms as possible, this movie is also all about youth.

That is, as much as a movie so fearful of death can be about youth, and vigor. When the brothers chuck their, ahem, luggage at the end (to catch the train), the act is not simply some metaphor about mourning sons finally getting rid of their fatherly baggage. Rather, the film is saying that it is more important to watch the movie (to catch the train) than to hold on to things; those things (or their ephemeral essence?) stay with you no matter what, forever. Owen Wilson's Francis says, “Dad's luggage isn't going to make it” and the three brothers smile, and they run faster. Just like his missing loafer, the luggage doesn't matter, in the end. Those things are just distractions anyways. This both calls attention to the objects and tells you not to get hung up on them.

I guess what I'm trying to say is: sure, you can read the scene as a blatant metaphor for “growth” or something but that belittles what happens, and the things that matter are those characters and their actions. Besides, the characters are still covered with details, they still carry a lot on their faces and bodies. And having seen them through a whole film with those suitcases and handbags you know that they're more mnemonics than anything. And if we understand that memories are forever inside us then we realize that we don't need mnemonic aids. (Think of the funeral within the funeral: lives within lives and stories within stories.)

Still, Wes Anderson is of a tradition of filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino (or the French New Wave that so inspires both artists' work) that metabolize cinema. They take it up (all the time, from everywhere), digest it, and reproduce new films. This is perhaps most apparent in

Darjeeling in the musical cues Anderson borrows from Satyajit Ray. (But the only reason I know that this music is from those films is because I was told ahead of time. I look forward to understanding the homage better, and I thank you for the offering.) What's funny is I can also understand the music as a signifier for this odd Western ideal of India the boys are seeking. The music in Wes Anderson is an object weighted with (and by) history as much as things like suitcases. Think of the British Invasion tunes, too: in a story about youthful brothers on a journey into the spiritual unknown, the first song with lyrics in the film is by

The Kinks (a band comprised of brothers), called “This Time Tomorrow.” It's all about not knowing where the journey will take the passengers. The song, like Peter catching the train in slow motion, knows that to get anywhere you simply have to start going.

Which brings me back to thinking about how well the movie works. Most importantly, I think it's wicked smart: it understands movies, and stories, and how they work (internally as well as on an audience); the philosophy of the film is affirmative; it does not overplay its hand, or shoot for too big; every detail has a purpose (for story or for its affective resonance); it's fucking funny. However, one could argue I'm a biased party. I feel I “get” Wes Anderson movies. They “speak” to me. But what I've come to realize is that this affection I feel for them is not about identifying with the characters (the way I thought I did with Max in

Rushmore back when I first saw it). More so that, in as much as art is about life, I find my life affirmed in these films: my dreams, my loves, my fears, and my understanding of all that -- my understanding and enjoyment of life. One might argue this is all we ever look for in films and that is not a criteria but I would also like to posit, in as uncontroversial a stance as possible, I hope, that as much as art is about life, so is philosophy about life -- and in that film is a work of art, film can be a work of philosophy. So when I say Wes Anderson films speak to me, perhaps I mean that I am attuned to his brand of philosophy (pace

Cavell). Perhaps I've realized that life is never fixable, or able to be fixed, even in narrative; that life refuses itineraries, even if it is good to plan some things, or at least be prepared to deal with the unexpected turns in the night; that life keeps going, for everybody, always, before and after them, and especially during the present (no d’uh); that life is weighted but fast; that life can surprise and delight; that life is worth it, even if it's scary, and dangerous; and that life is funny.

Laugh with me,

Ry

____________________