— edited by Ryland Walker Knight

— The Yards

1.

Work is a part of life. ...an expression of life.

—

Orson Welles

2.

When I began writing, I always said to myself that my ideas were very shallow; that if a reader saw through them, he would despise me. So, I disguised myself. I disguised myself, in the beginning—I try to be a 17th Century Spanish writer with a certain knowledge of Latin. My knowledge of Latin was quite slight; I do not now think of myself as a 17th Century Spanish writer; and my attempts to be Sir Thomas Brown, in Spanish, failed upwardly. So, perhaps, I evolved a quite dozen fine sounding lies. Of course, I was out for purple patches. Now I think purple patches are a mistake. I think they are a mistake because they are a sign of vanity. And so the reader thinks of them as being a sign of vanity. And if the reader thinks of you, and he thinks of your modern affects, then there is no reason, whatever, whether he should admire you or put up with you. Then, I fell into a very common mistake: I did my best to be, of all things, modern. Now, there is a character in Goethe's

Wilhelm Meister's Lehrjahre [Apprenticeship]—the character says, "Well, you may say of me what you like, but no one will deny that I am a contemporary." Now, I see no difference whatever between that quite absent character in Goethe's novel and the wish to be modern, because we

are modern. We all have to strive to be modern. It is not a case of subject matter, of style.

—

Jorge Luis Borges

3.

Maria Callas is someone I can understand. That kind of solitude, of being alone in the world and wanting to be loved...I believe in love, not ideas, nor intelligence. Look where ideas got us! How can anyone believe in ideas after the Shoah? We must be wary of intelligence. This is another paradox, isn't it? Just like Guillaume and Rivette! It is very important to resist. One must always resist. That's what I am, above all: A resister. I will always resist ideas.

—

Guillaume Depardieu

4.

All my life I’ve been harassed by questions: Why is something this way and not another? How do you account for that? This rage to understand, to fill in the blanks, only makes life more banal. If we could only find the courage to leave our destiny to chance, to accept the fundamental mystery of our lives, then we might be closer to the sort of happiness that comes with innocence.

—

Luis Buñuel

5.

It is the dirty secret of all architecture, even the most debased: deep down all architecture, no matter how naïve and implausible, claims to make the world a better place.

—

Rem Koolhaas

6.

There are two basic ways that a filmmaker can relate to film history: to work within an existing tradition or to proceed more radically as if no one else has ever made a film before. I think it would be safe to say that at least 99% of the films we see in theaters are made according to the first way. The Danish narrative filmmaker Carl Dreyer and the American experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage are two of the rare exceptions who might be said to have followed the second way. Even though they too both worked to some extent in existing traditions, their principles of editing and camera movement and tempo and visual texture are sufficiently different to require viewers to move beyond some of their own habits as spectators in order to appreciate fully what these filmmakers are doing artistically. Without making such an effort at adjustment, one’s encounters with the films of Brakhage and Dreyer are likely to be somewhat brutal in their potentiality for disorientation.

Ghatak, I believe, is another rare exception who followed the second route I have described, and one who provides comparable challenges of his own. And his methods of composing soundtracks for his films as well as his ways of interrelating his sounds and images are among the things I would point to first in order to describe his uniqueness as a filmmaker. One might conclude, in other words, that he reinvented the cinema for his own purposes both conceptually, in terms of his overall working methods, and practically, by rethinking the nature of certain shots he has already filmed—–specifically, by starting and/or stopping certain kinds of sounds at unexpected moments, sometimes creating highly unorthodox ruptures in mood and tone.

It might be argued that these ruptures were not necessarily intentional. At least I’ve found no acknowledgment of them or of many of Ghatak’s other eccentric filmmaking practices in his lectures and essays such as “Experimental Cinema,” “Experimental Cinema and I,” and “Sound in Cinema,” all collected in

Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema (Calcutta: Seagull, 2000). But by the same token, I find little if any acknowledgment by Carl Dreyer of his unorthodox editing practices in his own writings. And the issue of artistic intentionality remains a worrisome one in any case, because artists aren’t invariably the best people to consult about their own practices, and it can be argued that what artists do is far more important (at least in most cases) than what they say they do. And the radical effect of Ghatak’s ruptures in his soundtracks strike me as being far better illustrations of his manner of reinventing cinema than any of his theoretical statements. To put it as succinctly as possible, they reinvent cinema precisely by reinventing us as spectators, on a moment-to-moment basis, keeping us far more alert than any conventional soundtrack would. And this makes them moments of creation in the purest sense.

—

Jonathan Rosenbaum

7.

Any passion that is not eternal is hideous.

—

Balzac

8.

If I had not existed, someone else would have written me, Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, all of us. Proof of that is that there are about three candidates for the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. But what is important is

Hamlet and

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, not who wrote them, but that somebody did. The artist is of no importance. Only what he creates is important, since there is nothing new to be said. Shakespeare, Balzac, Homer have all written about the same things, and if they had lived one thousand or two thousand years longer, the publishers wouldn’t have needed anyone since.

—

William Faulkner

9.

I don't feel that the cinematograph was just a way of putting the present in a box for the future. There is in these [Lumiere's] films a recreation of the atmosphere of the period that is exactly what we love today in Godard. When we look at the very first films, they're almost all extraordinary. You feel like using the word "genius." But these cameramen weren't geniuses—they were helped by the fact that technique was still difficult. I find more fantasy in certain Lumiere films than in paintings that aspire to fantasy. It's the creation of a world that exists in reality, but also of a world that exists in the imaginations of Theodore Rousseau or the Lumiere cameramen. The angle chosen by the cameraman — a humble servant of reality—is the work of his unconscious talent. Many great works of art are the result of the unconscious. I would even say that when a film we've made works, it's in spite of us.

—

Jean Renoir

10.

And though it may be madness, I will take to the grave

Your precious longface

And though our bones they may break, and our souls separate

- why the long face?

And though our bodies recoil from the grip of the soil

- why the long face?

—

Joanna Newsom

11.

Just because a person's dead doesn't mean they've changed.

—

Bette Davis

12.

To digress briefly, because this is a very nice little story: there was an old professor of film giving a course on direction, and he showed Dreyer's film

The Word (1954) to his students. At one moment, a few of the students laughed during the film, and after the end of the film, the professor said to them: ‘Look, if you start laughing when you hear the word 'God,' you're never going to make a film.’

I tell this story because filmmaking is a very real and serious profession. Serious means heavy, and sometimes the weight of things can be very heavy. The weight of feelings is something to handle with balance and common sense, and so we must never laugh when somebody speaks about God or the Devil. In effect, when we speak of God or the Devil in cinema, we're speaking about good and evil, we're talking about people. We're speaking about ourselves, about the Devil and the God in us, because there's no God up on high, and no Devil below.

It's correct because all the things in front of you, all the themes that you can try to film in your lives as directors, these are always very serious things, even the comedies or the gags that Chaplin filmed. These are always very serious things which, at bottom, are related to good and evil.

—

Pedro Costa

13.

I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking. What I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear. . . .

What is going on in these pictures in my mind?

—

Joan Didion

14.

I just want four walls and adobe slabs for my girls

—

Animal Collective

15.

Many things have happened to me, as to all men. I have found joy in many things—for example in swimming, in writing, in looking (at a sunrise or a sunset), in being in love, and so on. But somehow the central fact of my life has been the existence of words and the possibility of weaving those words into poetry.

—

Jorge Luis Borges

by Mark Haslam

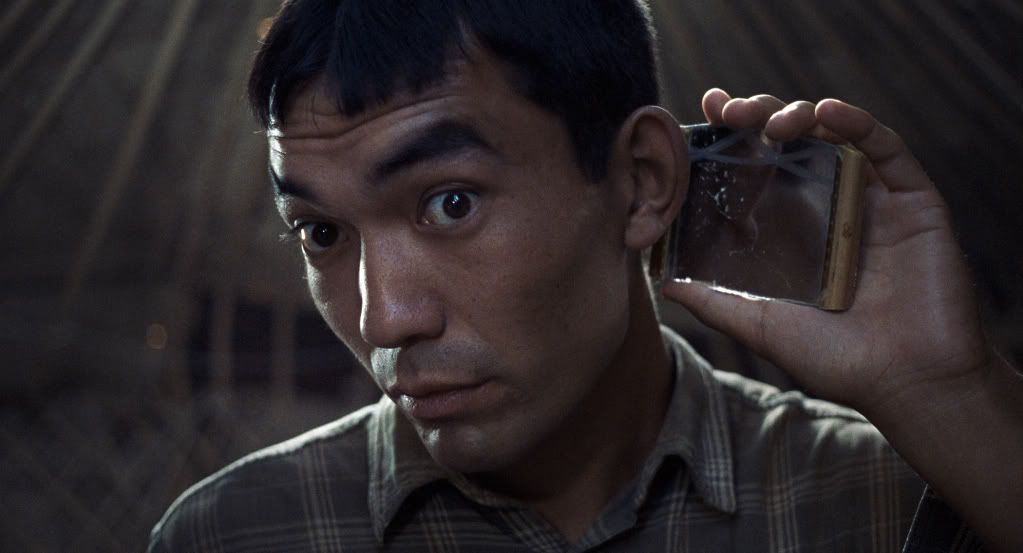

by Mark Haslam I went to Jaime Rosales's Bullet in the Head for two reasons: one, I'd heard that audiences had been walking out of it in droves, that it was 'difficult'; two, I couldn't get in to see Greenaway's Rembrandt's J'accuse. The 'difficulty' of Bullet is that there is no dialogue: the camera takes an embodied position, so that its position, which is always distanced from our main character, can't hear what anybody is saying. The narrative becomes a document of this man's daily life. Here he is with a friend in a cafe, there using a public telephone, here now at a party, going home with a woman, driving a car, etc. Yet these don't seem like 'difficult' concepts to me: space and voyeurism have been brought to higher levels of consciousness in film many times. Then again, I think (and the film gives you plenty of space to think) that 'voyeurism' might not be the right word—and here enters some 'difficulty'. We don't feel as though we're looking in on a life. The shots are too composed, all too orchestrated, don't feel at all like surveillance. Of course, a film like Rear Window is carefully composed—but there voyeurism lays beneath narrative; isn't, as here, the narrative itself. Moreover, a level of terror enters into each shot because of the title, which announces an event we think we know will happen. But do we want to see it? What agency do we have to not see it apart from leaving the theater all together? We're not voyeurs at all. We're not looking in, we're being shown, being made to watch. It terrorizes its audience, and I wasn't sure how I felt about. It seemed a different kind of terrorizing than that of, say, Michael Haneke, who deals with many of the same issues as Rosales. Where Haneke, for me, is a great success, I'm not sure about Bullet in the Head. I need to give it some space.

I went to Jaime Rosales's Bullet in the Head for two reasons: one, I'd heard that audiences had been walking out of it in droves, that it was 'difficult'; two, I couldn't get in to see Greenaway's Rembrandt's J'accuse. The 'difficulty' of Bullet is that there is no dialogue: the camera takes an embodied position, so that its position, which is always distanced from our main character, can't hear what anybody is saying. The narrative becomes a document of this man's daily life. Here he is with a friend in a cafe, there using a public telephone, here now at a party, going home with a woman, driving a car, etc. Yet these don't seem like 'difficult' concepts to me: space and voyeurism have been brought to higher levels of consciousness in film many times. Then again, I think (and the film gives you plenty of space to think) that 'voyeurism' might not be the right word—and here enters some 'difficulty'. We don't feel as though we're looking in on a life. The shots are too composed, all too orchestrated, don't feel at all like surveillance. Of course, a film like Rear Window is carefully composed—but there voyeurism lays beneath narrative; isn't, as here, the narrative itself. Moreover, a level of terror enters into each shot because of the title, which announces an event we think we know will happen. But do we want to see it? What agency do we have to not see it apart from leaving the theater all together? We're not voyeurs at all. We're not looking in, we're being shown, being made to watch. It terrorizes its audience, and I wasn't sure how I felt about. It seemed a different kind of terrorizing than that of, say, Michael Haneke, who deals with many of the same issues as Rosales. Where Haneke, for me, is a great success, I'm not sure about Bullet in the Head. I need to give it some space.