The things you made

by Ryland Walker Knight

Dear ewe,

Earlier today, the good folks at GreenCine Daily hit "publish" on this little paean to what I've often told you is my favorite film. I tried to get at a few things in the piece, but, as can happen, I lost my way. I wanted to talk more about address and philosophy and arrogance but I figured (probably correctly) that this would have far exceeded my duties, or at least the desired scope, at hand. I decided somewhere in there that I'd write you a letter about what really interested me watching the film again last week.

Suffice to say, it looked great on that HD television upstairs, even if I worried I'd gotten the settings all wrong and that Caviezel's face was in fact stretched fat. Further, even through shitty components it looked better than the old Fox disc I've carted around for so long. Nothing will replace a theatrical screening. (Or my first, somewhere after Christmas in the latest days of 1998, amidst some pinballing around LA's belt of plain concrete with my mom for a New Year's Eve "celebration" with her folks. You can imagine how psyched I was, all of 16 and proud to know who Terrence Malick was, having seen his two almost-forgotten 1970s features on VHS tapes my dad'd either rented or bought.) In any case, the restoration looks great, as you'd expect from those Criterion folks. Big surprise.

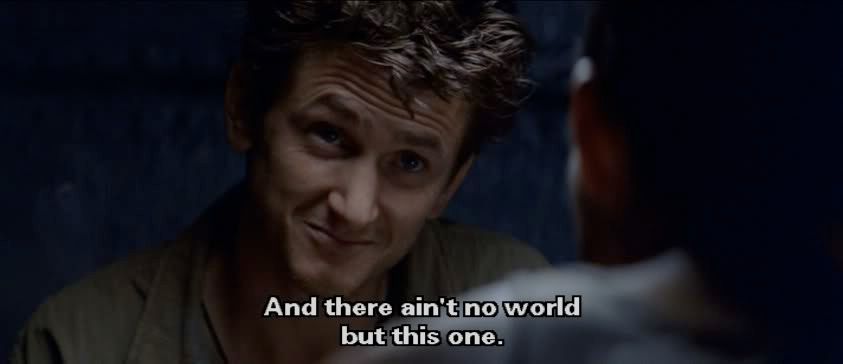

What did surprise me was how watching it loud, as Terrence Malick instructs via text before the film, really changed it again. Over the past twelve years, I'd been so obsessed with the images and the words that I forgot how bombastic the action scenes are, how often you hear a warbler, how certain actors' breath sounds clipped or how bodies fording grass fields can sound like a record played backwards on low volume. The wind sounds like wind, not bad microphones. And the voice-over work became more mysterious. I was certain for so long that Sean Penn'd said those last lines, the famous ones about shining I entertained tattooing on my left arm, but now I'm not so certain. Not that it matters. Each timber carries a different affect. I wouldn't be surprised if Malick made a bunch of young men record the same words and chose whose tenor suited the light best after the fact in post-production.

(How indulgent a working method! Yet also: how typical of a bright mind. Amass as much evidence and build the best argument; or, gather your groceries and get creative.)

This unmoored voice, ascribable to any, seems the defining characteristic of the film. I'd bet not too many people would disagree. My dad, for instance, always complains he can't tell who's talking. He needs that clarity for a fiction to work, he needs a representative element. (Or so it seems from our talks.) Again, I don't think this is uncommon. What I find so fascinating, though is that position's opposite: the delicious confusion of an overlay, like the white noise of some shoegaze rock, or the layers Wes Anderson makes 100% literal in so many of his slow-motion tableaux. A phrase that got morphed in my essay was "splay valence." This means something very specific to me, so it hurt to be asked to change it for clarity's sake, and slabbing down "layering meaning through a variety of aesthetic effects" felt exactly anathema to the alliterative fun of my prior, um, contrivance. It's also a bad definition. What's so comforting about Malick's movies is consistent with all my favorite works of art: they confirm certain philosophies I harbor about the world, specifically about wanting the world and wanting to be in the world. That is, they confirm my desire to want to live. You know that about me: it's about life, about living, for me. It? Art, mostly, but more simply anything, including life itself. So many hours we've talked this summer about how you want to live, what we're doing independently to find and make and lead the lives we want. (Of course, it'd be better if we could congrue those aims more often, ie, live near each other, but the world doesn't allow for everything we want all the time, including our wanting it.) Which is a long, indulgent way back around to these voices and their seeking, their questions, how they aim to get at the world's (and life's) mysteries. And, as we talked about last night even, there's all kinds of answers to pour yourself into—but it's the forfeit-others choice that helps define things. What I (and I think you) find so phenomenal about The Thin Red Line, in the end, isn't that it simply "accepts the mystery" (I know you're growing to hate the Coens) when that voice asks for his soul to join him but precisely that we can ask for that, for our selves to cohere, and see the world we want. And then use our powers to foster this world.

Too bad there's always got to be money involved, eh?

A world of love,

ry

No comments:

Post a Comment