Brief Thoughts on France, the French, and the Rest of Us.

by Mark Haslam

[Part of VINYL IS HEAVY's Bastille Day celebration. Click here to see our index. Click here to view all the entries at once. Ed's note: Mark is a friend from school, another cinephile I like to talk and sometimes disagree with (re: Haneke). I'm happy to have him on VINYL: he's a smart, kind guy with a discerning eye and good taste — for the most part. Look for more from him in the months to come.]

France (read: Paris) is the place film dreams of, the place where films can dream. The limitless possibilities that Hollywood’s Golden Age represented to the world in the Thirties and Forties migrated in the Sixties and Seventies to France—at least, to France as depicted in the cinema. I remember, as a young cinephile-to-be, sitting down with Godard and Melville and Cocteau and Renoir and Truffaut, and thinking, “This is where film is.” Okay, maybe I’m giving young Mark too much intellectual cred…but still, there was something in their work that made film real, made it seem as though it came from this place—that Les Quatre Cents Coups, for example, wasn’t simply made in Paris, but that it had already existed in Paris, had already been lived and was still being lived each and every day by each and every Parisian.

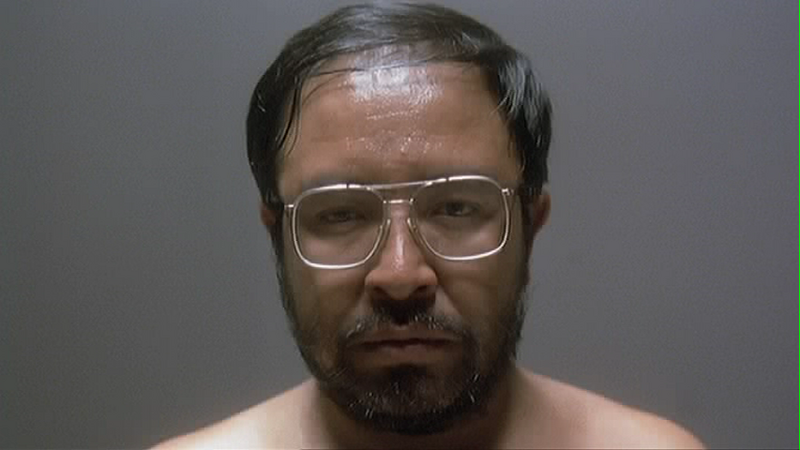

And this, I think, is the draw of France and its movies for those of us that aren’t French: the draw of a place where film, simply, happens. So, in thinking about French cinema, I found myself thinking about it as it is in the hands of non-French directors. Buñuel was always brilliant, but not until he left the oppression of Franco-run Spain did he make something as perfect as The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (only one of the several masterpieces he made in France). More recently was Michael Haneke, whose Caché represents, for me, the possibilities of cinema in France, while his English language remake of Funny Games represents the ability of a Hollywood aesthetic to ruin a film (a film I’ve long admired). There plenty of filmmakers to think of here, but it was Krzysztof Kieslowski that ultimately occupied my mind. Kieslowski didn’t make any films in France until the Trois Coleurs trilogy at the very end of his career; yet those three films to me seem so involved in the idea of “France” and the idea of cinema that the two seem to lose any distinction.

The colors of the French flag (blue, white, red) compose the visual landscape of the trilogy (Bleu, Blanc, Rouge). Yet never does it seem that the colors are inserted into these films—they are not done up or painted onto the settings. Rather they are brought out of their locations: the blue of a window’s reflection, the red of a car’s brake-light. Here are the colors as they always are, Kieslowski’s camera just makes them apparent to us (I spy with my little eye something with the color…). The colors begin with definition (blue = liberty, white = equality, red = fraternity), yet the moment the films begin they gradually work toward abstraction. Red seems more like a warning of division, or a kind of divisive passion, not a sign of fraternity. And the supposed liberty of Bleu is more of a hollowness—each instance of the color a reminder to Julie (Juliette Binoche) of what she no longer has: a husband, a child, both of whom died in a car accident she survived.

Julie tries to forget her past (as her Alzheimer’s-afflicted mother has), leaving behind or destroying what remains of her husband and child. But her attempts to carve out a private niche fail. The world, in fact, who awaited her husband’s composition celebrating the unification of Europe, will not let her. And neither will the film, which also strives for a sort of “unity” in its color scheme.

So the pool, where Julie finds a sort of freedom, betrays her.

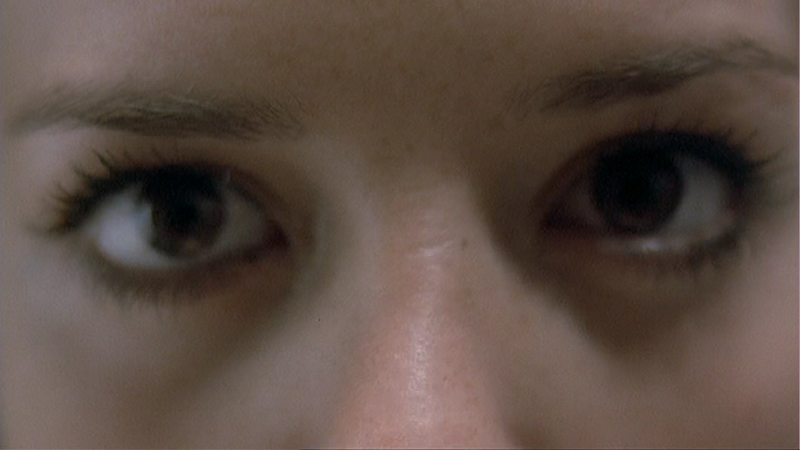

She is discovered, and then invaded.

What sort of liberty is this? Julie is at the whim and will of her environment, and blue becomes the question of liberty, rather than its affirmation. Can liberty exist for her? What form would it take? Liberty is a only a possibility, always present as blue, but, like color itself, never fully graspable. Similarly, Bleu’s languid pace opens the possibility of something to happen—the freedom of any occurrence at any moment—but doesn’t allow the possibility to become a reality. When, finally, something begins to happen (a relationship between Julie and Olivier, the completion of Julie’s husband’s composition) these things shatter in the final five minute sequence: images, barely moving portraits of all the characters we’ve encountered, fold over and dissolve into one another. But each image is also a depiction of constraint or captivity: Julie pressed against glass; the necklace a noose for the young man; Julie’s mother in the retirement home losing her memory; the unborn child in the womb; the stripper in shadows; a painted figure in an eye; and finally Julie, again behind glass, with the slowly encroaching reflection of blue.

During this sequence, the Unification of Europe piece plays, but whose version is it? Julie’s? Her husband’s? Olivier’s? The loss of definition—precisely what Julie seems to have felt throughout the film—becomes perhaps the liberty of expression. As we watch her compose music, the visual field blurs.

The Colors Trilogy presents not the clarity of expression, but the movement toward clarity, which is inevitably unclear. I guess, then, Kieslowski both complicates and confirms the idea of France as a place for cinema to happen: these are films that portray the potential of occurrence and of creation, both of which exist and are denied in France and in cinema.