by

Ryland Walker KnightIt’s a shame

Quentin Tarantino is so tight with

Robert Rodriguez.

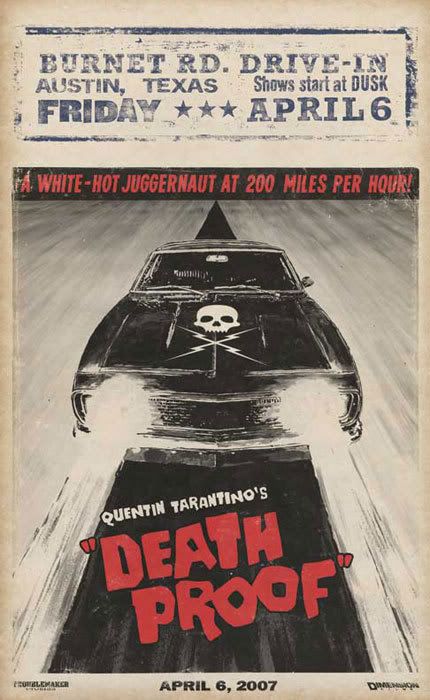

Grindhouse, their new joint opus of nonsense, doesn’t have to be coherent by design but it’s so backloaded by Tarantino’s brilliant

Death Proof that one wishes one could just skip over Rodriguez’s inane

Planet Terror to get to the good stuff right away. Much how

Kill Bill was mostly spoiled by its marketing split (it deserves to be three hours, unlike this mess),

Death Proof is tainted by an apparent geek-out greed fest. As we’ve been given it, as the backend segment of

Grindhouse’s carnival of idiocy,

Death Proof’s glee almost erases

Planet Terror’s numbing parade of bad choices; had it stood alone,

Death Proof would be one of the best American movies of the year.

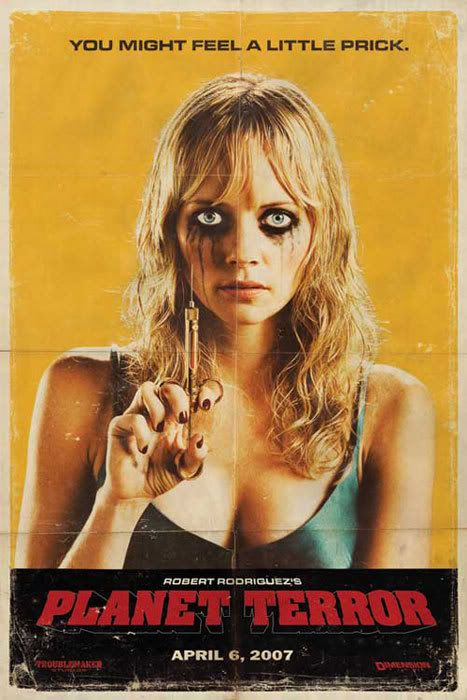

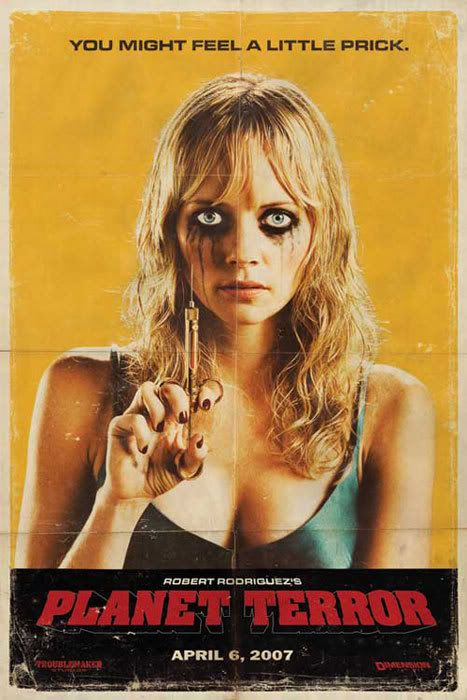

The problem with

Planet Terror (and all of Rodriguez’s movies, really) is he’s not quite as smart as he thinks, nor does he try to be as smart as he thinks he’s attempting to be. His idea of playing with the audience is to spoon-feed it clichés with a smile and pat them on the back for recognizing said clichés. It’s not really post-modern as much as post-thought. He does do casting right, however, and to see

Jeff Fahey and

Michael Biehn play brothers is something of a treat, even if it tastes kind of shitty and looks like gruel. Really, though, I doubt I’ll spoil it by saying, yes, Rodriguez goes there and name drops not only the US involvement in Afghanistan but

Osama Bin Laden — and, as expected, it is hardly a novel surprise to make the government the ultimate evil or kill off key characters late in the third act. And Rodriguez is fully aware of this since each turn is wholly schematic — and banal. So, watching

Planet Terror is kind of like saying “D’uh!” for 90 minutes.

There’s a little light ahead when three fake trailers are shoehorned in between the features (there’s also one that opens the, uh, experience) that are almost worth something. At the least, the one made by

Edgar Wright (of

Shaun of the Dead fame), called

Don’t, shares a similar wit and skill with

Death Proof that, briefly, shows you all the possibilities of this trash genre Tarantino has so expertly perfected: a hyper-awareness of the medium manifest through puns (visual and auditory) and the silly joy of watching movies.

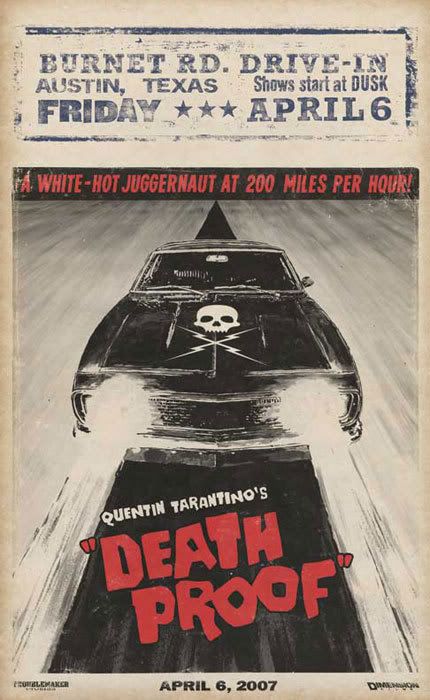

Death Proof

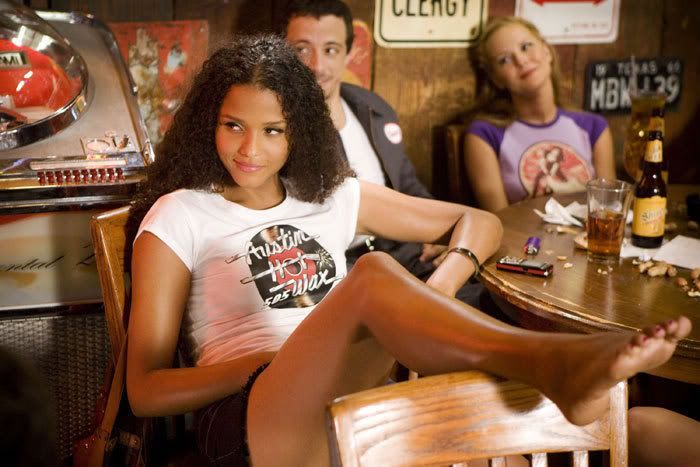

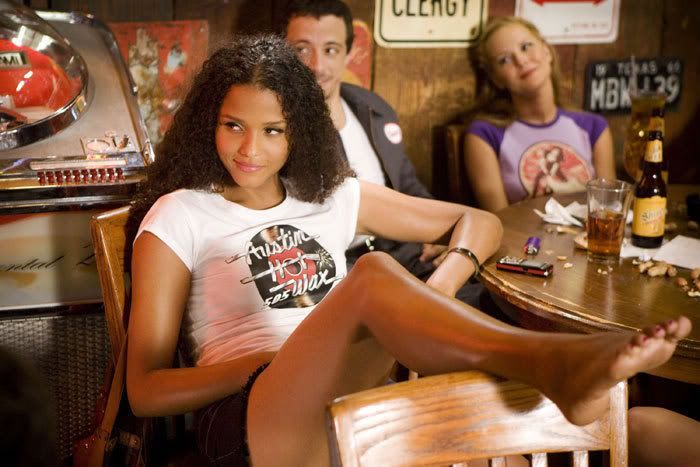

Death Proof’s first great move shows the delicious

Vanessa Ferlito racing up a flight of stairs holding her crotch saying, “I have to take the biggest fucking piss of all time.” We’ve just watched a movie and this implicates the audience — of course! we need to pee, too! — so, whether or not those in attendance do, in fact, need to urinate they’ve already begun to think about it. Later, closer to the end but before the quite literal climax (more later), Rosario Dawson is told to stay in the backseat of a car and has a door slammed on her dialogue as she pleads, “But I really have to piss!” Tarantino knows people are watching this and those people are people with bodies and fears and needs and, being whip-smart like his most obvious influence

Godard, he plays with his ever captive audience and its bodies and fears and needs. I really had to piss too.

For all his fanboy inanity and no matter his actual intentions, Tarantino, unlike his buddy Rodriguez, makes smart films that are fully aware of the film medium — and how it works onscreen, and on an audience. His films demonstrate his realization that film is not necessarily or primarily a narrative vehicle. The narrative is always subsumed by the spectacle in an unexpected, peculiar fashion. Despite this insistence on visuals, however, there’s a greater insistence on words, as in Godard. Both these filmmakers toy with narrative progression to the point where it’s hardly important but each knows how to make it resound with the audience, somehow, dramatically or not. Again similar to Godard, Tarantino’s films appear narrative but are really outright incidental captures: things just happen. And a lot of those things are awful.

Death Proof

Death Proof stars

Kurt Russell as Stuntman Mike, owner of a

black 1971 Chevy Nova, who may or may not really have been a stuntman and says he was on a lot of television shows from the 1970s. But the young girls he’s telling his story to have no idea what he’s talking about. His story isn’t validated, he’s not trustworthy. He’s just some creepy dude with sideburns, a frightening scar along the left side of his face, a goofy pompadour, a satin rainbow driving jacket and a badass muscle car. The

Hostel director

Eli Roth cameos long enough to say Stuntman Mike must have cut his face falling out of his time machine. Our knowledge that this is an homage (and campy send-up) is winked at once again.

Yet, try as he may, Tarantino’s attempts at camp always play earnest. His best film, 1997’s

Jackie Brown

, is a similar homage/send-up of a similar exploitation genre but it plays it straight at all times, even with the deadpan jokes (even

Chris Tucker). The few times

Jackie Brown gets a wicked grin and winks at the audience it’s not for any camp value, it’s for love, as in its deadly final sing-a-long scene.

Death Proof’s signature camp moment is pure joy but also one of menacing hollowness: Kurt Russell stands at the door to his so-called “Death proof” vehicle (which, from the inside, appears empty and made chiefly of metal roll bars), watches his target car drive away and then turns his head to look straight into the camera for that wicked grin that erupts into a laugh. Of course he’s going to kill. But this glee is the scary thing. It’s important to note, though, Stuntman Mike’s glee is not Tarantino’s glee. Mike’s first kill is horrific, not orgasmic. That comes later.

In what may be the biggest formal stroke of brilliance in

Death Proof, the movie is split in two like its host,

Grindhouse. And, as the film only gets better, the second half of the second half — while name-dropping and visually quoting

Vanishing Point by way of a very specific car — is unlike anything else, yet the same as everything else in movies: it

is the joy of movies. It’s what

Kill Bill should and could have been. Simply, it’s a movie about chasing tail that chases tails all over the map and yet, oddly, while chaotic, it's more unrelenting and rigorous than Cronenberg’s

Crash. It’s fucking absurd. It adores the absurdity. And it’s absurd how much fun it is to see so much terror and wreckage and, most shocking, the glee of it all its bloody fallout. We forget we have to pee and we surrender to the hell ride. We almost want to be

Zoe Bell (Uma Thurman’s stand-in for a lot of

Kill Bill’s stunts) out there on the hood, defying death, proving she’s the one who’s death proof, clinging taut and lithe to centimeters of iron. (Tarantino’s nimble camera adores her limbs, too.) And like Rosario Dawson’s ever-widening smile, we get giddy, we are overcome, we tap that ass and we shoot our hands to the sky!

When

Tracie Thoms’ Kim smashes the

1970 Dodge Challenger 440 (with a white paint job) through an out-of-water, abandoned boat stranded aside the road and Dawson screams, “Did you just hit a boat?!” the absurdity is eruptive. Seconds later Thoms yells “I’m the horniest motherfucker on the road!” That

Death Proof ends in a devastating orgy of blood can’t come as a surprise but it certainly is a welcome release. Tarantino’s film ends abruptly, like the jarring absence of the missing reels (another possibility Rodriguez plain ruins and Tarantino nails), but, being sudden, we aren’t allowed to question the spectacle — it’s its right to do that, just as it’s the women’s right to do what they do, however terrifying. Still, it’s too bad I had to sit through

Planet Terror beforehand.

[This is Quentin Tarantino, he will fuck you up.]02007: 191 minutes: written and directed by Quentin Tarantino & Robert Rodriguez and Edgar Wright, Rob Zombie & Eli Roth.

[This is Jungle Julie, she will fuck you up.]