By Ryland Walker Knight

NOTE, 9/24/2011: I decided to repost this in its entirety here because the formatting on the new Slant-housed HND post is all screwy. I trust Keith won't mind.

NOTE, 9/24/2011: I decided to repost this in its entirety here because the formatting on the new Slant-housed HND post is all screwy. I trust Keith won't mind.

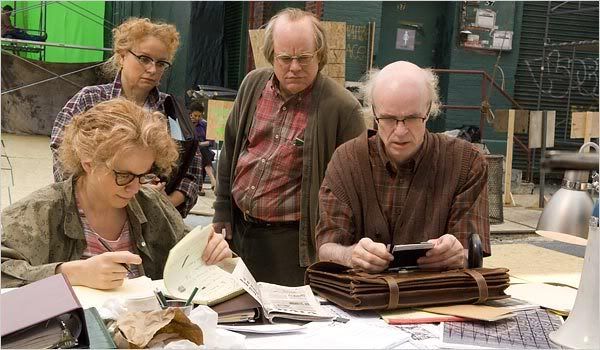

I am not alone, I am certain, in coming late to the Arnaud Desplechin party poised to jump off this winter. His latest film,

A Christmas Tale, already garnered plenty of accolades from those lucky enough to see it at Cannes and/or the NYFF (two takes I dig:

GK's gushing and

MK's lucidity). It played in San Francisco last month, too, at the Clay, as centerpiece of the San Francisco Film Society’s inaugural French Cinema Now program (dig

MG's interview, too). I missed it, on purpose—I was watching Jia Zhang-Ke’s

The World across the Bay—because I knew it would be released soon, and would probably be a big deal. Looks like the case; the snowball is gathering speed and size. This election week saw not just something righteous for our country but also, on a decidedly smaller scale (like, minuscule, dude), the start of IFC Center’s current Desplechin retrospective,

Every Minute, Four Ideas, as a build-up to next Friday’s New York release of

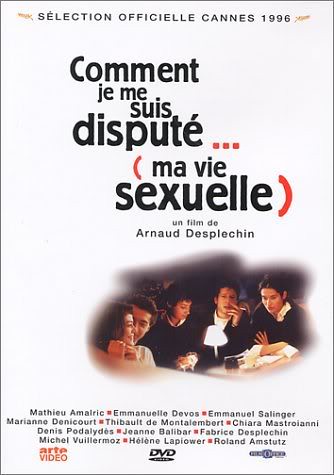

A Christmas Tale. Lucky for me, I got to see two of the other Desplechin films shown at the Clay: his rare debut, the deliciously abrupt

La vie des morts (

more Maya), and his calling card, perhaps,

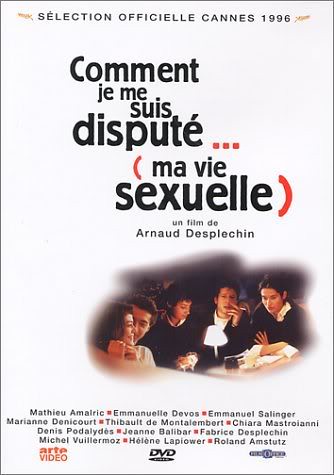

My Sex Life… or how I got into an argument. Since then I’ve revisited

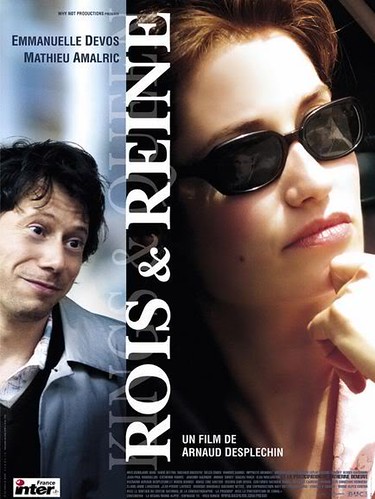

My Sex Life, on Fox Lorber’s abominable DVD release, as well as his 2004 freight-train

Kings and Queen. Smart cinephiles that they are over there, the IFC Center has programmed both of these for this weekend, including the possibility of one rich, long, seductive, dark-all-day double bill on Sunday.

Early in

My Sex Life,

Mathieu Amalric’s Paul Dedalus talks with his cousin, Bob (Thibault de Montalembert can grin), about Bob’s new girlfriend, Patricia (Chiara Mastrionni may be more irresistible than her mom)—specifically about how great her ass looks—and Bob asks Paul to be more inspiring, to quote someone. Paul counters with Kierkegaard: “Is there anything more sparkling, more dizzying than the possible?” It’s easy to see Desplechin in this madness: his films are giddy with cinema, brimming past the point you think they should reach for only to delight you with more, more possibilities and more actual delights, more concrete details to complete the picture. Like Truffaut, whom he acknowledges as monumental and inspirational, Desplechin makes films that look simple at first but (pace Kent Jones) take on a protean charge, eager to move into something new, to grab hold of a moment, if briefly, before rushing forward.

My Sex Life... is nearly three hours long but it never flags; it pauses, it fades, but it never halts; it asks to be followed; and it’s so goddamned endearing, so charming, that it would be foolish to resist. Or, that’s how I feel. See, it’s hard for me to separate myself from Desplechin’s films. They invite the viewer, much like Truffaut, very much unlike Godard or Rivette, yet it’s not simple and naïve assimilation. Of course, it’s easy to weep looking at a mirror, and I have, but, for every reflection, Desplechin offers at least three more angles on any given scene-space. It’s that maxim the IFC Center has appropriated, which Desplechin initially appropriated from a letter Truffaut wrote to Jean Gruault, screenwriter of

L’enfant sauvage: every minute, four ideas. What makes Desplechin so vibrant (yes, violent, too) is his commitment to the speed of this creed within a grand architecture of cinema.

My Sex Life... should promise, mathematically at least, 688 ideas; I did not count, but it feels like there are more. That’s a lot to contend with, and it’s easier in the watching than in this writing, which is funny because Paul, our ostensible hero, opens the picture sleepwalking, refusing to finish his doctorate, refusing to write, because, well, just because: because it’s tough work. It’s easier to wallow in pretension and hurt than it is to do things. (And, as

Stuart Klawans argues, Desplechin is perhaps the most Jewish non-Jew in cinema—and isn’t Judaism a religion of faith in action? —I realize many devotions may argue this point in their favor but it seems inherently Jewish to me; it’s not Kierkegaard’s possible but rather akin to Nietzsche’s allegiance to creativity. This much is true and open to be countered: I have not seen

Esther Kahn yet. I do not have the full picture of this argument as does Klawans. But I want to, yes, I want to, as ever, to see more—I’m greedy like that—to grab and digest more, and more. I hear myself in the Kierkegaard as much as in the Nietzsche. I hear and see myself, all too much, all too often, all too human to ignore it, in these Desplechin films.) But, of course, despite its cast of academic types,

My Sex Life... isn’t about the ivory columbarium; while he does spout off at length, mostly about pussy, we never see or hear any of the work Paul does; the closest is his late rant that culminates: “It’s not Heidegger climbing some fucking mountain. No, it’s the girl’s face, it’s your fear, as you pull back the elastic, her belly … you see?” If the film is about academia, it understands such a life as a kind of death—as something to shuck, to shake free from, to flee. It’s right there in the title: it’s a film about life, about sex, about me! See? It’s an invitation to look back at your self! It’s no different than any other work of art!

About two-thirds through the picture, we take up the thread of Paul’s put-upon long-time (ex-)lover, Esther, played with fierce liveliness (loveliness!) by

Emmanuelle Devos, whom, despite no marital bond, I like to see as Desplechin’s Gena Rowlands. As much as Mathieu Amalric’s goofy grin buoys and motivates this film, Devos anchors its pathos. It was during her direct address speech that I finally began to let the weight of it all fall onto me, curled alone in that fourth-row seat—that I first began to cry—through a smile. The first time I saw the film, it started at noon on a Saturday at the Clay, smack atop Pacific Heights in San Francisco, and I did not know the Blue Angels would be performing patterns in the sky above the city that afternoon. Roughly the moment Esther began reciting her letter, so did the roars of jets leak into the auditorium, and I thought, “Brilliant! It’s a film about love as a flight as much as a fight after all!” The fact that the planes did not cease their aural (and aerial) contortions through the remainder of the film made me question this argument, naturally, but it was too delicious a strand to let loose. It makes sense, after all, however the happenstance played. Love is a flight from the real, or reason at that, into clouds of stupidity and luxurious hurt. It makes the pained descent dig deeper, of course—that return to the ordinary—but, we begin to realize, as does Esther in that shower near the close of the film, that the daily muck makes sense, too, and affords us the next opportunity to fly—a new possibility is forged. Flight remains a thrill and tears are a form of baptism. The world beckons.

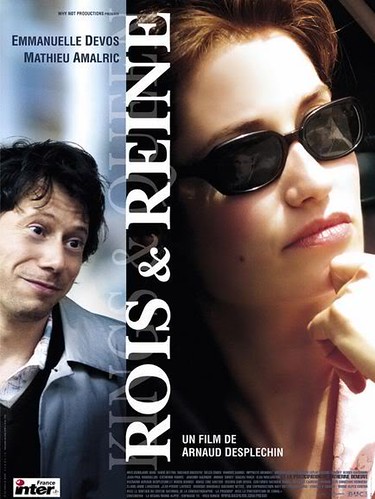

Devos and Amalric appear in relationship, again, in

Kings and Queen, only further removed. It’s nice and fun to play the cinephilic game and imagine these characters, Nora and Ismaël, as extensions of Esther and Paul, but the fact remains that they feel lively and real, here, and all their own and all too human because Desplechin is so interested in their singularity—and because these are two enormously talented actors. The biggest difference is simple: Devos and Amalric are older, and they bare (and bear) their lives all the more in their gait and their lines and their faces. If we can accept that Devos is a French Gena, then perhaps we can agree that Amalric is some kind of Frog Faulk; but, if

Kings and Queen resembles any Cassavetes, it resembles

Love Streams, which pits husband John against wife Gena as brother and sister leading a twinned, braided life negotiating how to love one another. At one point, Nora says of Ismaël, “If I’d had a brother, I’d have wanted one like him.” We might say

Kings and Queen is about the love available (yes: possible) in a family—and what makes family, where you draw the line. We might also say this later picture is an inverse of the earlier in that

My Sex Life details Amalric’s Paul’s love of three different women (all some kind of “wife”) while

Kings and Queen muscles through Devos’ Nora’s love of four men (all some kind of “husband,” even her son). Formally, too, they diverge:

My Sex Life... operates on a logic of occlusion and expulsion, the frame crowded and held—until the tears and the blood and a shower rain down;

Kings and Queen, despite a continued affinity for long lenses and their resultant density, jumps through spaces, cuts frequently, feels more frantic, violent, locomotive. We might say, finally, that

Kings and Queen is (like

My Sex Life…, I suppose) about what it takes to get mobile in the world—and Desplechin’s continued answer may remain magnanimity.

—Did I mention these films are hilarious? Nora’s half of

Kings and Queen is melodramatic, very heavy, full of tears and harsh lessons, full of shouting, full of death, but Ismaël’s half is, in Desplechin’s words, “a burlesque comedy.” Being a smart guy, he’s spot on. The irony is startling, lucid, simple: for all Nora’s mobility and affluence and lightness, it's Ismaël who finds joy in the routine—in captivity, no less—despite being a mopey goof whose posture is so aching, so desirous of Real Life—while it keeps happening Right In Front Of Him. Like, you know, that beautiful and desperate young thing, Arielle (Magali Woch might melt in your hand, not your mouth), whose answer-made-flesh seems too easy to be true at first. Their offhand non-courtship is one of the loveliest and silliest I’ve seen; again, I couldn’t resist its charms. And, again, Amalric’s echo

de moi-même (most notably in sessions with his voluminous, infamous psychiatrist, Dr. Devereux, played with great wit by Elsa Wolliaston) makes me wince and aspire in equal measure towards something new and thoughtful. In short, in their hilarity, Desplechin’s films stage, say perform, a moral posture (which subtends invitation and challenge) that echoes (again) Nietzsche, and his forebear Emerson, that argues for gaiety as a form of seriousness. But this is never easy, of course; nor is it quite attainable; it’s something to seek. For Ismaël, this adventure is fraught with a net of troubles of his own creation that, like a cape, he must simply untie and fling off. For Nora, it’s a bit more complicated: she has to kill. This picture of womanhood, however generous, is where you know a man made these films; but, as Ismaël says, in what will prove out (I'm fairly certain) as one of the great film monologues, to Nora’s son, Elias (Valentin Lelong is too cute), “that’s not a failing, that’s a quality.” What’s lovely is that the films know this, too, and, it’s true, they are unabashed: they seem to get off on it.

But a yummy montage of Marion Cotillard dancing in her panties isn’t strictly about the pleasure of looking at her, at the curve of her neck as much as the curve of her breasts or the light in her eyes; no, it’s just as much about how easy (how dumb) it is to fall into thoughtless love with a girl just because you like the way she bounces. She remains a human, impervious and strong, with the force to bowl you over, by virtue of the film’s interest in how fleeting this sight is, despite its lingering imprint. Nakedness is a fact, like rain. When Marianne Denicourt sits naked at the close of

My Sex Life..., echoing Cotillard like she echoes her own nudity earlier in the picture, it’s not about turning us on (however much such a sight will titillate us heterosexual males) but rather about impressing us that, yes, we spend some time naked. We play naked. Nakedness is readiness, an acceptance, and shared with another body it's an agreement as much as a delight. (This is, of course, a different picture of nakedness than that of Jean Eustache, but I'll save that argument for later.) It makes sense that

My Sex Life... opens with Paul's literal awakening and closes with its deferred significance at bedtime, highlighted by a memory of a game played on the floor, looking down at pieces asking to be picked up with care (I'm talkin' Pixie Stix here), while Denicourt hugs herself across the chest.

I once wrote a free-associative essay for a zine called “Baggy Like A House.” I don’t remember the essay any longer, nor do I possess a copy, but I remember that phrase because it was directed, in the essay, at the reader, and I’d like to rewrite it, say revise it, for you who are here: you hang baggy like a house about me, and I keep running after you just as you keep running after me. I have only offered a few ideas, four maybe, for all the time you've spent reading, so please go soak up some more in that theater if you can. If you’re in New York, do yourself a favor and spend this rainy weekend with some fun frogs trying out life, seeing if it fits, and shucking sheaths as they please, as they run towards the door, towards the clouds, towards some kind of love, some kind of naked, some kind of possible, some kind of life.