[This is the first part in a rather lengthy email conversation between Jennifer Stewart and Ryland Walker Knight. For readability, the call and response pairs will be split up. I'll update each intro with links as we pump out the rest. For now, though, here we are, looking all around, trying to make some sense of that first weekend. There are spoilers throughout. Consider yourself warned! Certain forms of hyperbole will not be tolerated in the comments thread although we are curious if you have a thoughtful response to offer in order to continue our conversation. Just, please, don't make me turn on comment moderation. Nobody wants that.]

Jen --

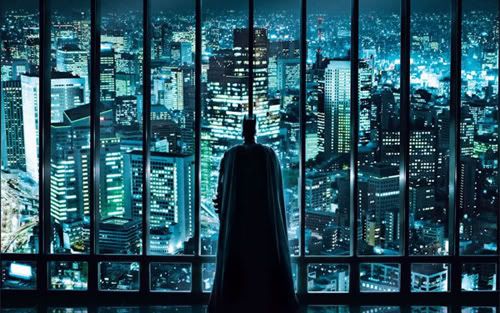

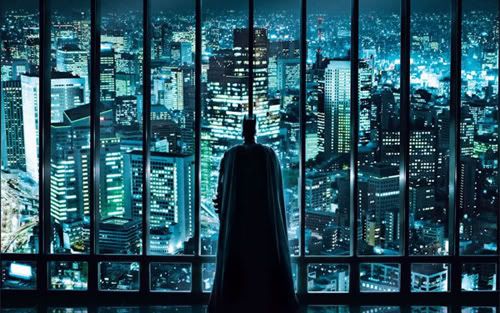

From the top: I dig it. I don't think it's the masterpiece some have claimed, but neither would I call it a bankrupt endeavor, just complicated. As a picture of the modern city (and its consequent perils), in a time such as ours, this is probably as good as a pop artifact can get.

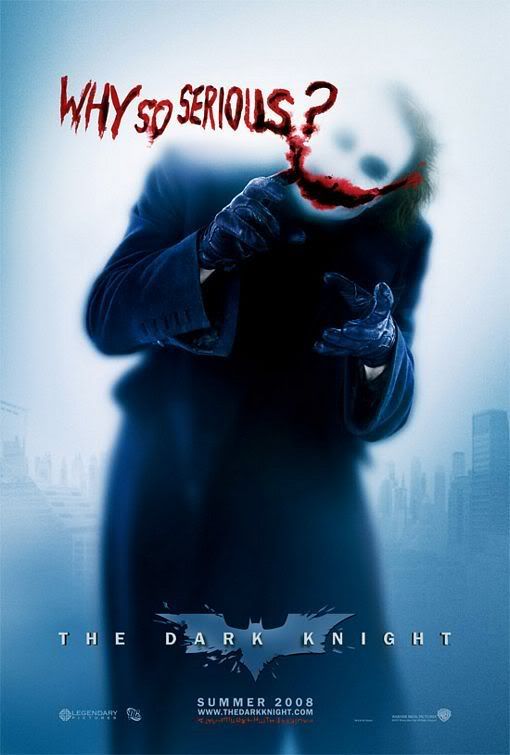

The Dark Knight may not have

Michael Mann's poetry of imbalance (an unfair comparison despite the opening heist's nod to

Heat), but Christopher Nolan's nearly anonymous Gotham has all the right sheen and transparency, grime and emptiness, shadows and nightfall terrors to scare you of its dark arena of violence. It's the insistence on the city -- in swirling helicopter shots most of the time -- that makes it more than a Batman movie and less a Batman movie than before.

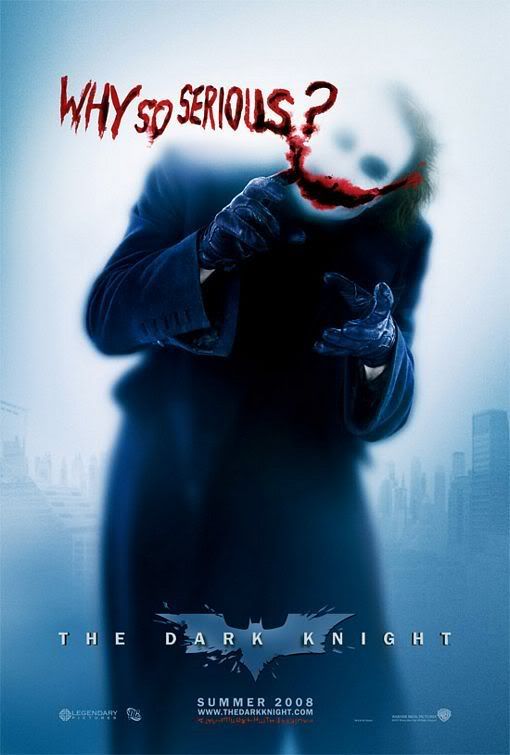

After all, it's the first Batman movie where Batman is just another part of the ensemble. Christian Bale may get top billing but he's by no means the star, much less that interesting (a shame). The real acting fireworks, so to speak, happen between the poles of Heath Ledger's typically hyperbolic Joker and Gary Oldman's beautifully understated Jim Gordon. Oldman's portrayal of decency grounds all the anarchic overflow of Ledger's embodied chaos.

However, all too often chaos is more a talking point than an element of the action. That's probably my biggest problem with the movie: Nolan doesn't really know how to shoot action scenes. Or, more pointedly, he doesn't shoot fight scenes well. For all the kinetic activity, those handheld close ups make these encounters less about movement than about fractured collisions that can't find a visual resolution in space. Which is a silly, hifalutin way to say, it's too often cluttered and fussy, if oddly dynamic. I'm puzzled by his close-in action mise-en-scene, and (I worry) not in a good way. That said, the film is edited pretty well and the timing on the wide shots inside action sequences is pretty spectacular. That mack truck flipping has a real weight -- which is aided by the sound design. Again, it's hard to compare him to Michael Mann, or even Paul Greengrass, but those guys are more interested in space as an arena full of possibilities and energy (something I dig); Nolan's idea of space is more pragmatic, logical, showing an interest in the where but not the how. For instance: I dig that the climactic high rise site is open and under construction, open to plain sight, as it gets at the illusion of spectacle (and how we make or account for appearance in this Gotham) once more. And I dig how the sonar plays into that, too, but all the encounters within that structure are pretty straight forward, a series of scenes of Batman deploying pawns in the way of the final showdown.

What makes the action interesting, in the end, is how Nolan gives each sequence significance before and after, pointing away from the action. (I think this is why I liked

The Prestige so much: it isn't an action picture.

The Prestige is about magic, about manipulation, about spectacle, about perception; and here all his editing patterns make more sense. He's forming a way of seeing there (looking for details) that doesn't quite cohere in

The Dark Knight.) In the most simple sense, the context for the action in

The Dark Knight is the current mood of the country: the fear of unknowable threats, of ultimatums without rules. There's a lot of easy allegories to draw. But that's all abstracted enough into ideas about chaos (those talking points) and seriousness so that I trust the film will play when the next administration's getting ushered out of office. However, all that falls to the Joker, in monologue form, which speaks to Nolan's interest in story. I think he fashions himself a storyteller more than a filmmaker; at bottom, it's how Nolan and his brother Jonathan escalate the consequences of the plot with each successive sequence that makes

The Dark Knight so compelling. If ever I was to appropriate that Bordwell term, it'd be here: Nolan has mastered "intensified continuity."

Okay. On the one hand, I'm impressed you were so ready to let this film whip you around and rattle your soul. On the other, I don't think the film earns the boat scene with Tiny Lister or

Walter Chaw's description of Maggie Gyllenhaal's resigned acceptance as "the single most heartbreaking moment of 2008 cinema." Further, what I find so dark is not really all the terror and wreckage throughout the film but the final lie Batman concocts under the assumption that people won't be able to withstand the morally complex truth of Harvey Dent's rather literal fall.

But this makes it sound like I only dislike the picture. And I don't. For the most part I dig it. I'm just caught up in my formal/aesthetic criteria here and not moving to how this picture, and its popularity, might be significant, if, by nature, blown way out of proportion. Maybe we can get into that a little more as we progress.

--ry

Ry,

I'm in a strange spot. I've come to the tentative conclusion that my feelings for

The Dark Knight are, well, just that. They're oddly resistant to qualification, yet smolder indignantly to hostile, very well-written reviews like

Adam Nayman's for Reverse Shot. Not that I'm unthankful for you sending Nayman my way. But somehow it and

Dark Knight has spawned a kind of crisis for me. Either I don't know who I am as a viewer, or I don't know what matters in film criticism. So I might be asking you to guide me back to the light. But first, hear my plight.

The problem is that

Dark Knight really got to me. And like, 5 movies total have ever gotten to me. One of them was last year, at the Castro Theatre's special advance screening of

There Will Be Blood. Previous was David Fincher's

Fight Club, which I saw opening week, in 1999's Ottawa. What they all have in common, is that I was really shaken by each of them. And it was sublime.

I knew from Ledger's first scene that

DK might deliver another such catharsis. I'm speaking of an intense kind of - for lack of a better word - pleasure, and it makes most or even (*gulp*) every other film experience pale in comparison. No, I think I mean that. I love

Contempt and

Battle in Heaven and

Gosford Park and many other films. I can still conjure Reygadas' 360 sequence shot from

Battle; the tingles it and other moments in that film gave me. (Still haven't seen

Silent Light....). And I don't want to mitigate what those films are to me. Yet I don't know how to compare them to Nolan's

Dark Knight, because

DK created moral peril which actually, really threatened me. And that was riveting. I walked out not able to think of precedents, unlike

TWBB's immediate conjuring of

The Shining and

2001. But, then, on my second screening, when, in the interrogation cell, Joker laughs at Batman's missive fists and desperate demands to know Harvey and Rachel's whereabouts, it came to me like lightening: Tyler Durden. Fincher's and not Mann's or Greengrass' sense of action (more on that shortly).

Unlike Nayman, I had problems with

Begins and thought its sequel better realized (casting REALLY helped). I'm tempted to say Nayman's problems with

DK can be explained simply as, the film wasn't what he'd decided he wanted. Yet his impressive review made me second-guess my own enjoyment of the film. Could I have been wrong somehow?

A growing problem for me with film criticism is how easily formal concerns along with a kind of privileged ethics are made exclusive and essential. For example, I want to care about your worries over how Nolan realizes action. But I mostly have a hard time following them. I do like your point that if the action is shot closed-in, then we get fractured collisions (of say, body segments) rather than framed total movements. But why is that a problem? To me this simply signals different themes and concerns - quite literally, a different perspective on the action. Does action require a total view of bodily encounters, in order to "find a resolution in space"? You said 'twas all really just complaining the actions shots were cluttered and fussy. I guess I just don't see that. Or, even granting your premise, don't see why something else would necessarily be... better, somehow? In fight sequences, Nolan's camera goes in close so that Batman can appear and disappear suddenly - the sense of his superlative movement is created by these cuts that let his outline outstep the frame, even when centered in it. Fincher liked showing us local reactions to blows, and Nolan may be after something similar, which means the total scene of bodies having room to manifest the forces both impacted and exchanged during a fight just isn't the right profile for the shots. I'm likely in over my head here, so perhaps I should just say: you seem to be assuming there's a way to shoot action scenes, and Nolan ain't done it. Help us (me) scrutinize with your eyes: Who or where does that premise come from, and why should I care about it, especially when in order to see anything amiss in the film, it seems to first need assuming?

That said, I'm happy to say I strongly agree with you that

Dark Knight ain't doing anything dark through themes of chaos, and certainly not as film-noir dark as some have hastily claimed. The triumph of

DK's big moment is that Joker assumed more chaos than he could engineer: people are more attuned, less individualistic, if a little less civilized (in the bad, Rousseau sense of loosing sympathetic trust) than he imagined. Chaos in the film is simply Joker's attempt to remove some of the (already perhaps flimsy) partitions supporting an ordered edifice of civil morality. (Civil morality as in the ideological commitments to the sense of fairness that underly law, the courts, and the judiciary - also, the related concepts of what one should rationally desire and fear). Joker's desire not just to lay bare but to rip down these partitions - revealing the panic-inducing expanse of amorphous, unscripted moral interpolation - is seen realized in Gotham's inner and outer design. Nothing has proper walls: Dent's office, Bruce Wayne's bunker and penthouse -- all pillars and receding perspective lines, shelves and desks with only open, surface conspicuity. Even in Lau's Hong Kong architectural marvel, the walls and drawers are glass, revealing everything and waiting to be shattered. The precariousness of moral infrastructure: you take a vote on a ferry, but ooops, this isn't enough to resolve the threat. (Wasn't democracy suppose to be our political panacea?) I guess we could call the result 'chaos,' but despite his speech to (by now) Two-Face, Joker is certainly, definitely, a planner. He is an engineer, a scientist, and he'll say what it takes to realize his experiments. Joker's response to the ferry passengers' inadvertent solution to the prisoner's dilemma (why did I have no jade and all cathartic relief at that moment? Is there something wrong with me?), is to lament that all must be done oneself. I agree with Nayman that Gotham is the anonymous hero of the film, for the film sacrifices the false stability and irrational vulnerability of electing heroes to be "the face" of, say Justice. The city needs much more than one "white knight" who is willing to let his face bear the investment of justice. One wall can't hold up an edifice. One face can't take that much.

You said Nolan may be more of a storyteller, than a film maker. Well, I like stories. I like them a lot, because they shake me and I'm not sure but that might be one awesome reason to be alive. Images shake me too, and they can tell a story with images and/or with actors. Ledger and Eckhart and Oldman and those huge empty spaces with transparent partitions, was some of the best shaking I've had.