Thatches and blankets. Out of the Past and Nightfall.

by Ryland Walker Knight

[OR: "David Goodis at PFA so far." Nightfall played Thursday, August 7, 2008, as part of PFA's current Streets of No Return: The Dark Cinema of David Goodis series, which continues this Thursday, the 14th, with a screening of The Burglars, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Omar Sharif. The series runs three more programs thereafter through the 23rd. I hope to offer some more thoughts next week.]

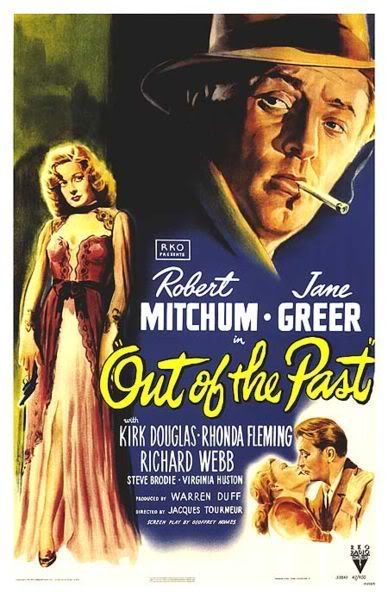

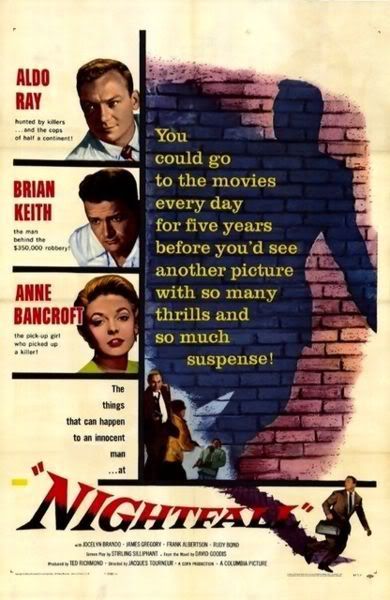

Eddie Muller specifically asked last Thursday's audience to not compare Nightfall to Jacques Tourneur's earlier proto-noir, Out of the Past, so I'm going to do just the opposite. In his introduction, Muller said that it's a fruitless comparison, that it would only do harm to the later film, but I think they make a fine pair precisely because they are so divergent (yet remarkably consistent). Made a decade apart (1947, 1957), both fear the city and its traps, both distrust people, both seek escape from the world. However, the paranoia of the former is eased, slightly, in the latter into circumstantial nuisance: Jane Greer precipitates an economy of lust, her come hither enigma lighting desire like a good femme fatale, whereas Anne Bancroft rather represents a haven, her curves safe and her eyes welcoming. Nobody owns the upper hand in Nightfall, really, over Aldo Ray's Art Rayburn/Jim Vanning -- he's fighting time, and the seasons, as much as the villain bank robbers -- while Robert Mitchum's Jeff Bailey/Markham, from his first encounter with Joe Stephanos (that sly, fey and lovely analog to Greer, Paul Valentine), finds himself trapped by history (his story), by people, by plots, by desire.

Tourneur didn't seem capable of making a dull image, even in the almost-bland patches of Nightfall's location exteriors. Part of this may be due, simply, to the print and its upkeep, although the picture has a less striking, more television-grade contrast/construction than its predecessor with fewer set-ups and less glamor. Yet an early dolly retreat, to make way for a bus that fills the screen, is a signature, subtle Tourneur move; and in the day for night interrogation sequence at a derrick field, the flat light does not take away from the compositions. Everything lays at an angle. Even direct, 90-degree frames sit uncomfortable with objects thrust in on a slant, fudging perspective. Tourneur's world is acentered and fluid, despite its classical trappings, the termite auteur par excellence, littered with odd interstitials to syncopate the mise-en-scene. While more pronounced in the earlier film, the more modest later work still rests uneasy, growing out of the performers as much as the technique. Aldo Ray's hemmed posture and choked voice work at odds with his broad Navy body. Anne Bancroft can't quite get comfy and fades into the picture, another prop, almost; something else Ray has to carry. As the go-nowhere villians, Brian Keith and Rudy Bond play off each other so well that it's easy to forget all the other calm-crazy instantiations of other heist duos; Keith, especially, uses that laconic distance to genteel effect, rounding a square character as much as possible.

What I find most curious through the first two weeks of the David Goodis series, situated firmly in the middle of cinema's century, is how often things end well. The series opened with Dark Passage, Goodis' splash project. A Bogie-Bacall film directed by Delmer Daves, Dark Passage opens brilliantly, almost exclusively in first person point of view shots, keeping Bogie off screen until he has reconstructive plastic surgery to hide his identity (a San Quentin break-out) until he can prove his innocence, or simply flee for good, as he winds up doing. It's a pretty goofy film, to be honest, but its leads' charisma and chemistry buoy the plot and help sell every melodramatic turn, including its aw-shucks ending, as some kind of idea of what it takes to make your future, to make your dreams real, even if it means forsaking your past. I had to skip the second picture, The Unfaithful (unfortunate since it sounds compelling), and I'd seen Shoot the Piano Player before (a fine, smart picture), so I next caught up with the series with Nightfall. It seems to really do Steve Seid's program justice one should go ahead and read a Goodis or two, but my final weeks of school prevent too much outside reading (I'm slow and swamped), so I feel I'm only getting half the picture. Adaptation is an interesting, demanding process that seems shaped as much by studio demands as authorial concerns, at least in this early phase.

What I find most curious through the first two weeks of the David Goodis series, situated firmly in the middle of cinema's century, is how often things end well. The series opened with Dark Passage, Goodis' splash project. A Bogie-Bacall film directed by Delmer Daves, Dark Passage opens brilliantly, almost exclusively in first person point of view shots, keeping Bogie off screen until he has reconstructive plastic surgery to hide his identity (a San Quentin break-out) until he can prove his innocence, or simply flee for good, as he winds up doing. It's a pretty goofy film, to be honest, but its leads' charisma and chemistry buoy the plot and help sell every melodramatic turn, including its aw-shucks ending, as some kind of idea of what it takes to make your future, to make your dreams real, even if it means forsaking your past. I had to skip the second picture, The Unfaithful (unfortunate since it sounds compelling), and I'd seen Shoot the Piano Player before (a fine, smart picture), so I next caught up with the series with Nightfall. It seems to really do Steve Seid's program justice one should go ahead and read a Goodis or two, but my final weeks of school prevent too much outside reading (I'm slow and swamped), so I feel I'm only getting half the picture. Adaptation is an interesting, demanding process that seems shaped as much by studio demands as authorial concerns, at least in this early phase.  Nightfall is a meager thing, and as Seid's pre-screening read from the novel suggests, plenty was left unfilmed -- in particular because of its black and white film stock -- sticking to the plot and little else; however delightful those brief asides with the Frasers are (James Gregory and Jocelyn Brando are the most theatrical actors in the piece, clearly relishing their screen time), the passages operate as exposition, not color. And that's the biggest difference between this later film and Out of the Past: things breathe more in the darkness of the earlier work, each set (and each set-piece) another layer of story, mood, complication. By contrast, Nightfall looks more open, more blank, and allows for more projection; for a film named after night, there's a lot of day, a lot of white. And yet, it's another source of indetermination. The threat in Nightfall is precisely the chance that those empty spaces will be filled by guns and violence, that the wide white blanket at the close has buried things is untenable. Aldo Ray says he wants to keep the money company at the film's close but we don't get to see him and Bancroft and Gregory surround the satchel. It sits solitary, the lone dark spot in a bright field. The music plays triumphant, conclusive, but the image is stark and forlorn. Ray's Vanning/Rayburn may be exonerated and free to start life over with his new bride but it feels undercut. Or, the picture may simply be saying it's a first step; night will fall again and cover this once more. As we may remember from the beginning, the night brings artificial lights that isolate. Indeed: what will Vanning/Rayburn return to? Will he adopt this new name for good, as he tells Gregory's Fraser? Who is he now?

Nightfall is a meager thing, and as Seid's pre-screening read from the novel suggests, plenty was left unfilmed -- in particular because of its black and white film stock -- sticking to the plot and little else; however delightful those brief asides with the Frasers are (James Gregory and Jocelyn Brando are the most theatrical actors in the piece, clearly relishing their screen time), the passages operate as exposition, not color. And that's the biggest difference between this later film and Out of the Past: things breathe more in the darkness of the earlier work, each set (and each set-piece) another layer of story, mood, complication. By contrast, Nightfall looks more open, more blank, and allows for more projection; for a film named after night, there's a lot of day, a lot of white. And yet, it's another source of indetermination. The threat in Nightfall is precisely the chance that those empty spaces will be filled by guns and violence, that the wide white blanket at the close has buried things is untenable. Aldo Ray says he wants to keep the money company at the film's close but we don't get to see him and Bancroft and Gregory surround the satchel. It sits solitary, the lone dark spot in a bright field. The music plays triumphant, conclusive, but the image is stark and forlorn. Ray's Vanning/Rayburn may be exonerated and free to start life over with his new bride but it feels undercut. Or, the picture may simply be saying it's a first step; night will fall again and cover this once more. As we may remember from the beginning, the night brings artificial lights that isolate. Indeed: what will Vanning/Rayburn return to? Will he adopt this new name for good, as he tells Gregory's Fraser? Who is he now?Such ambiguity turns differently in Out of the Past. For one thing, it's sexier. From the lateral camera moves to Jane Greer's neck, from the abyss shadows to Mitchum's passive ire, this film is about as desirable as possible. It's plain gorgeous. Only Roger Deakins seems to shoot darkness this well in today's Hollywood productions. Which is another reason Muller's right to warn against comparing these two. It's just not fair. However, there's a nice dissonance to draw out, a tidy dichotomy between the clutter of things forcing action in circumscribed contexts (Mitchum's a detective caught between people, and later a mechanic, a profession spent under and inside things-spaces-systems) over against drawing out a map on the blankness of the world (Ray's an artist working in water color who cannot remember crucial (spatial) facts, which is a characterization of him as an actor as well). But that's not all. You could just as easily talk about how the films figure emergence (of the past, of memory, of violence, of desire) or repression or sacrifice or actualization or disclosure or lies. And, of course, all those are related. For this is an art of relationships. An art where it matters that Mitchum sits across from the cinema but never enters, only hears it, and lets it score his first encounter with Greer's Kathie Moffat. She's an illusion from the get go. After all, nearing the close, she says it herself, while wearing what looks like a habit: "I never told you I was anything other than what I am: you just wanted to imagine I was." It's a sick joke: Look all you want, I'll keep drawing back; in fact, I'm barely what you want. But, heck, we know she's only luring us in again, right along with Bob, there. Indeed: I want to go there sometimes. And I'll go. And I'll get out alive. That's the fun, right?

See a companion image essay: There's a world out there.

This movies were so great on that times, the real horror that you can't feel watching the expression and the art of acting.

ReplyDelete