BANG BANG: Ryland Walker Knight

[BANG BANG is our week-long look back at 20!!, or "Twenty-bang-bang," or 2011, with contributions from all over aiming to cover all sorts of enthusiasms from film to music to words and beyond.]

My, How Impermanent by Ryland Walker Knight

Earlier this week my Indiewire ballot appeared. I still stand by it, I suppose, but even just a week after publication I itch to change things. In fact, the whole enterprise gives me hives to a certain degree. The whole idea of absolutes in general, in any context. If you take a look at that list, you'll see a collection of films, I'd wager, premised on contingency, or some form of mystery or mess or exuberance. Even the more "straight" narratives (Cronenberg's & Jacobs' portrait-films) exhibit an interest in how things do not fit, or ever fix into reliable—much less accepted, normal—forms. Perhaps the best term I can reduce this idea to is a favorite on this blog: navigation. Life's not a maze, but there are hurdles every day, including waking up, not to mention the unexpected tidal wave every so often. We're so used to the narratives we're given or that we give ourselves that eluding the unwanted can wreck a day, a month, a year. (Lucky me: my year saw hiccups and headaches but nothing got wrecked. Truth is, I had a fantastic year. And I'm grateful.) Naturally, I'm attracted to films about finding ways through life.

———

Finding a way to make movie-going more a part of my movie-watching has been difficult this year, the past couple years. Granted, I got to attend Cannes. But the pleasures of that were certainly "extracurricular" as much as within the salles and theaters. The dinners, the new friends, the jokes over whiskey and rosé with Danny and Adrian after long days. But I still cherish movie-going.

Early last week, in fact, I had the supreme pleasure to take in one of the best double bills in recent memory at the Roxie Theatre (with Brian, yes): the early show was Borzage's Moonrise followed by Renoir's first H'wood venture, the insanely under-seen and apparently under-recognized Swamp Water. Two films about the south made by not-southerners that understand the south and southerners in ways you rarely see anymore. (Of course, I'm not a southerner; I'm a Californian. My Okie roots are roots and my relationship to GA/SC is tertiary at best.) But aside from any obtuse anthropological/ethnological reading I can offer, the films exist and excel simply as films. Borzage's at his Murnau best and Renoir is at his dollies-everywhere (and "people as people") best. And they spoke to one another in delicious ways the way a double bill is supposed to work. Steve Seid usually knows what he's doing but this was a special program. The swamp has different narrative functions in the films, but in both the swamp is a hunting ground, a space of violence, something untamable that few can master or at least negotiate (or inhabit!). Again, this speaks to how I see the world at large. Life takes skills we never anticipate requiring, but nonetheless accrue. True to this optimism I harbor—inside an unavoidable but I hope healthy cynicism w/r/t life's obstacles, including people (above all people?)—both protagonists of these films find ways to join the world by their stories' ends.

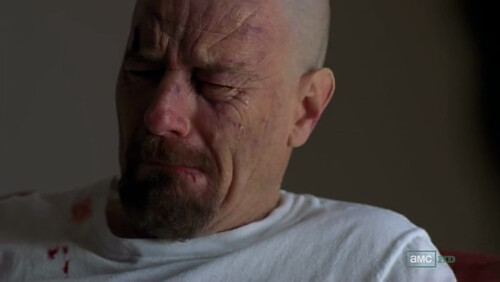

Then again, not every path is a success. The film I felt worst about leaving off my "official" top ten was Edward Yang's A Brighter Summer Day. That movie's all about the disconnect we're forced to confront as we grow through adolescence. It's about a lot more, too, including light, but there's a violence in adolescence that it understands (something Haz and I talk about as he is a teacher). This is true of all the Yang pictures I've seen, but this one is obviously special. Its length affords its narrative the space for us to observe characters rationalize their way through choices good and bad alike (though mostly bad) all the way. This is what critics mean when they call a film novelistic: time affording space for character. Granted, that's a limited view of what "the novel" is or can be, but this film in particular, as with many likewise classified films, is after a Dickensian kind of scope forever grounded in place and details. This, too, is how best to think of something like Breaking Bad, which Jen talked about yesterday.

Television, after all, is serialized much how the early money-making novels were; both are strategized as much as constructed with plot doled out in delimited chunks. But, as Jen noted, one of the pleasures of BB is just how digressive it is, how much air time is given to behavior and go-nowhere episodes of bickering. And it's not like this show's hopeful. It's got a pretty grim take on human desire and nature and intelligence. As I've said before, these characters are idiots. Walter White seems to have figured out a few things watching Gus operate, like the cost of survival in such a dangerous game as the drug racket, but he's still a bald, selfish, myopic stranger to himself and his oh-so-beloved family by the end of this last season. And the person he's closest to has every reason in the world to want to slit his throat.

———

I've been using my tumblr more than this home base throughout the year. Part of it is simply ease of use. Another is desire. The last is time. I like the scrapbook/notebook feel of the microblog. It feels like a repository of reminders. And it usually takes very little effort. Writing here is more work. (Writing anything is work!) Not sure what the new year will bring, but I'm not quite ready to quit my baby. But I quit making zines to make this blog and I may wind up quitting this blog to wind up making more films. Even if they're just little goofs about the sounds of seagulls or odd poems about light and memory. The future has more answers than me.

———

One thing I know for sure: though I've made some great friends via emails (cf. this week), there's a lot I'm proud of from this past year outside the walls and tubes of the internet. Thank you to everybody who helped make those realities real. You know who you are.

________________________________

Ryland Walker Knight is a writer and filmmaker living in San Francisco. He has three names, which you can read above, at left, and all over this blog.