by Ryland Walker Knight

[A note: Here we continue what Mark began back in Part One. (To see all the letters, click here.) We hope the letters continue, as we push forward into 2009, because we find this epic so typical of our (yes, fetishistic) interests in cinema as a tool for and of history; and of our aims as intellectually curious people of and in the world in general. I should like to say that these missives are hardly "polished" for a couple of reasons but that should become transparent soon enough. For instance: we are not done. Stay tuned for Part Three in the coming weeks.]

Mark,

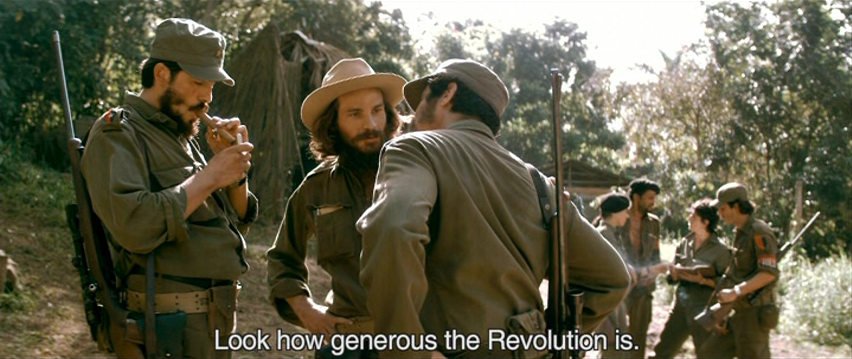

Your impulse to talk around the subject as a way to talk with the subject seems to mirror how Soderbergh's film works, of course, but what makes the film so curious to my eyes and ears is, first of all, how committed to its subject it remains. For all its distance,

Che is rather intimate. For all its landscapes, the close-up figures into a large part of its argument. However, the close-up operates in (if not diametric then perhaps) divergent registers across the film's intermission rift. In

Cuba, the close-up is pure affection, luminescent and loving expression; in

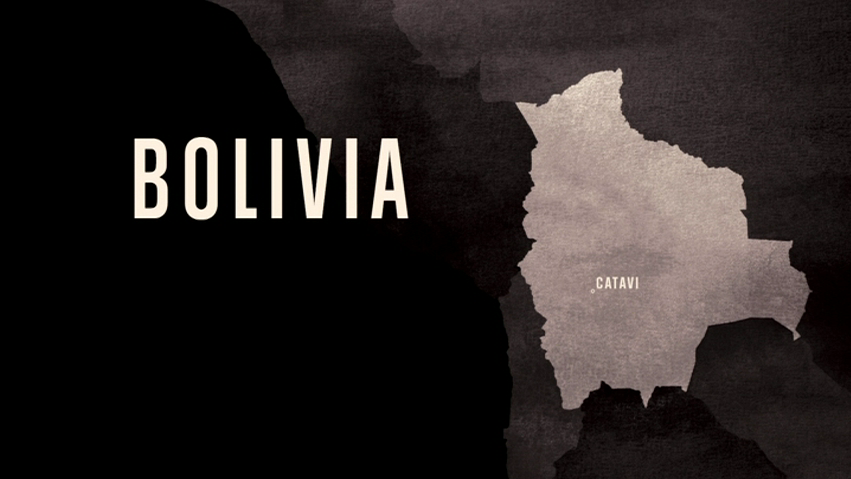

Bolivia, close-ups catalogue and segregate elements of the whole. In both halves, these sets form a crucial part of

Che's balance-equation in that their uses are explicitly related not just to form but how we witnesses will figure our "hero" at hand.

Reading

Hoberman's essay in The Virginia Quarterly Review shortly after reading your first missive made me think twice about your preliminary assumption-declaration that "

Che is not about Che." His essay begins with two weighty words for this man: "Ecce homo," which, of course, nods at Nietzsche and declares, with a colon, "this man." This man, Che, who means so many things. Hoberman lists a number of them, all fine labels, all fine in concert with each other, just as our sense of Ernesto Guevara is folded by so many forces of history and commerce and theory and philosophy and tradition and understanding and all tied to a single image appropriated (I want to say "abused" or even "slaved") into base, reductive, limited symbolism. My list here, as a response to Hoberman's, is an attempt to account for all those contradictory angles played in some name that really only means one thing at bottom: "man." It's redundant: this movie is about man, not just this man, but, of course, it can only ever be "about" this man in particular. And, as Hoberman astutely points, this man is a means for Soderbergh to explore personal obsessions such as process and technique. Look at any one of Soderbergh's films and you will find he is, indeed, or more than less, "a highly intelligent technician who sets himself a problem and goes about solving it."

Again, your question: how, if at all, do we approach Our Man, That Man, This Che? If we may see

Che as mathematics, as Soderbergh has arranged it to rise and fall like the sun, that ever-reliable reminder of our finitude, then perhaps we should do well to grant science its place at this martyr's table of conversation. No doubt the masses have silkscreened the Guevara myth to a new death, or depth. No wonder the aura is drained. No surprise Benjamin comes to mind. No way to get around the repetition of

Che. No modulation subsumed in total, the differences are shifts, the revolution a series without end: a perpetual reformation.

Others have said we must let the singular stand free, we must cherish and preserve these rarities. This challenge has largely been ignored by many of our (intelligent and critically thinking) colleagues. The exciting thing about

Che is that, as a hermeneutical situation unto itself (as any work of art is, or can and should be), it rejects a lot of the strict language of closed or isolated subjects—here I think of Sartre as the great mis-reader of Heidegger, and of Gadamer's lucid restorations—but rather an appeal to vulnerability, to the allowance for failure that participation wills us towards, or simply makes impossible to avoid. Here is my humble proposition that the freedom

Che argues for, while not that of Che's per se, is one where (useless though it may resound) tragedy looms. However, I do not want to say the film is defeatist. It may deny, but it ends on a boat, looking to the future (from the past), past a spray of light that triggers a reverse shot back at Our Che, standing bowed on the starboard side sharing fruit and looking wary at us, we whose gaze forges him as we wish.

The film is opaque yet transparent. A typically "academic" double move. And, indeed, Soderbergh's work is attacked as "academic." When will this cease to be a pejorative? When will the many under-readers—it's funny that those who tread the surface are hardly interested in a hermeneutics of surfaces and seek only to uncover the unknowable with an arrogance unavailable to my wary posture—begin to appreciate the fact that over-reading is, well, a virtue born of thoughtful attention to the world and its multifarious blossoming forth? When might we see the "real" revolution something like our blogosphere provides? When shall we shuck the calendar's arbitrariness to slow our rollout? When a real Marxism props up somewhere? —When will we get around to talking about the film?

I often wonder if my interest in film has mutated into an interest in what film, or

a film, provides in aftermath. I know this cannot be fully true as I do, indeed, keep watching. My watching has slowed so much in the past years because my watching now involves countless re-watching, revisions of my visions. I've said before on this blog (well, in a podcast) that the hermeneut's project is a compulsion, and it may not be healthy; I meant this to encompass cinephilia; this is old news. All of this to say: I do enjoy watching

Che. I find

Cuba gorgeous, if occasionally on the nose and a tad "cute," and I find

Bolivia devastating, and quite often yet more beautiful than its counterpart for all its drain, its pale weight of time and its canyon-cinema-circles. I find Benecio Del Toro's performance pitched perfectly between sex symbol and myopic asshole. I find Soderbergh's

mise-en-scène has not been this rigorous since his under-loved revision of

Solaris—which features similar arguments about beautiful, stubborn men contending with martyrdom and love and the process of history, or memory-making (all themes shared by his great, deft

The Limey; in fact these themes emerge present in all his films). I find the whole 257 minutes easily "too much" and nowhere near "perfect"—it's a "rush job" as much as Hoberman's "act of will" although it cannot nor should it ever be rushed. I find it impossible to recommend.

Che is foreign to itself like Che is forever foreign to his environment. His yearn for a united South America (present before

Cuba, if hardly seen here, and announced throughout

Bolivia) can never translate in practical terms for the simple fact that his fellows can never look past his face, his spectacle as a figure or a symbol. His comrades do not see his true singularity, his freedom of himself. Soderbergh may know he has no place in the world Guevara sought to build but he also knows that what we all look to Che for is that image of freedom that, as it is unavoidably poetic, comes only from exile. It's a negative freedom, if I understand, and, in a hilarious completion of one circle, a positively American picture that asserts our rights as humans to be a little crazy, to shuck rationale. Because, of course, freedom concerns our world, and not just humans; a space unanswerable to conceptual schemes, to maps of thought; a space given to productivity, to becoming made possible by our limits. Fitting, then, that

Che is situated by a pair of maps. Boundaries mean something. Che sought transcendence and all he got was an ignoble death in a hut. His myth, on the other hand, necessarily separate, keeps gaining. If Soderbergh's film can do anything in that space, perhaps it can remind us that this was a man and that man, like this world, will pass into history; however, if we look to build something we have already taken a step towards something.

Until then,

ry