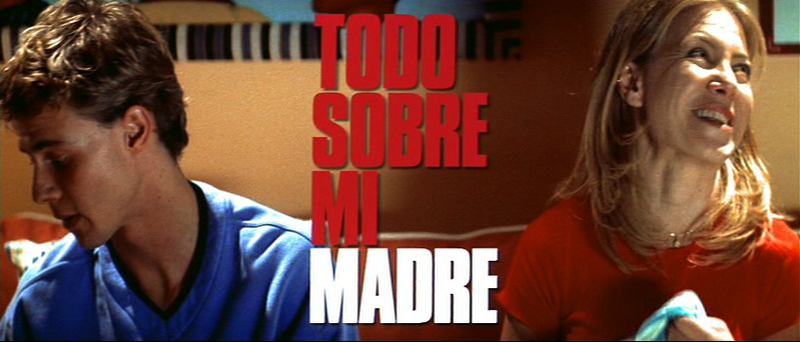

Melodrama Mondays: All About My Mother

by Mark Haslam

"Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience . . . We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy's impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character's pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside."

-David Foster Wallace

When it was released in 1999, critics hailed Todo sobre mi madre (All About My Mother) as an indication of Pedro Almadovar's "maturation" as a filmmaker. Return to those reviews and find the likes of “sobriety” and “depth” and “conviction” peppered about as evidence of this newfound maturity—all of which are placed in stark contrast to, as Andrew Sarris remarked in The New York Observer, “Almadovar's overtly gay sensibility..., canny distancing...[and] flair for voluptuous color compositions and sinuous camera movements” that made his films (cringe) “guilty pleasure[s].” Return to the film itself, however, and these estimations don't seem quite right: to shortchange Almadovar's style in this way is to ignore the fact that it's absolutely present in Todo. I'll concede—not that I'm actually debating with nine year-old reviews, but I'll concede that Todo sobre mi madre doesn't have the manic feel of Almadovar's previous films. But the style, that visual “flair,” as nebulous and uncertain as that word is, most certainly remains. I'll go so far as to say that it's exactly that “flair” (and I'll search for a better word in a moment), rather than some sort of self-restraint or self-censuring on the director's, is part of what makes Todo sobre mi madre what it is—that made that one teary-eyed critic shout, with the credits rolling, “Wring me out!”

What then is this “flair”? It's pretty easy, in naming it, to deploy terms like pizazze and passion and grandiosity, and even easier to makes terms up, like over-the-topness, and, you know what, they're all decent descriptions of Almadovar's style. Yet we know, at the same time, that they're insufficient, that they don't really describe the thing we're feeling: a feeling that I see as a trait of all melodrama, a feeling that I hope to explore more over the course of this column. I think Almadovar tries to elaborate on this style—our feeling—in the first twenty minutes of the film, which form a sort of prologue, an introduction to the narrative that begins after them. I want to focus specifically on the sequences that lead to the first death in the film, the incitement of narrative, that of Esteban, only son of our main character, Manuela. So let's see what it is we're feeling. Let's try to recapture it, as best we can. Let's watch.

It's the night of Esteban's seventeenth birthday. He sits, writing, in a cafe, waiting for his mother to arrive. In the background is a giant poster for the play he and Manuela are about to see. The focus of the poster are the two massive blue eyes of Huma Rojo, staring at Esteban, at us. Indeed, the poster (the eyes) begins in focus, shifting second to Esteban in the foreground (a perspectival shift seemingly enacted by Huma's eyes). Manuela comes in, looking for her son. The head of Huma (which could almost be confused for Manuela's) looms behind and dominates her in the frame. And yet we see, now, with Manuela in the picture, the 'pixels' that compose the poster—that is, we see the artifice. Or, better still, we see the things that make it big, at the very moment that we note the bigness of the shot itself: Manuela's bright red coat and those red red lips, even the pixels are red: so, we're not only seeing different (practically competing) red things, we're seeing Red, itself: we're zooming in to the point that we just see Color: or, we zoom in just enough that we're shown the abstractions that composes the image. The image, in this way, interrogates itself. And, really, isn't that what Huma's eyes seem to be doing? Interrogating. Observiving. But that interrogation isn't simply the interrogation of self-reflexivity. This is why Almadovar begins the film with consciousness. Here, to me, is the brilliance of these opening minutes, for the self-awareness (mostly) disappears after them, so that it's not so much deconstruction as it is construction we witness—a building up to and of the film. We have to see, in the first twenty minutes, the production of fictions, but especially of this fiction. (Recall Esteban, writing down what is presumably the title of the film—a moment of inspiration—and then immediately after the title appearing on the screen.) Yet it's a fiction that hasn't really begun. That won't begin until Esteban dies.

What, then—or is it, who?—is being interrogated? Of course, there's no single answer to that question. Two possible answers, though, would have to be: Melodrama and the Mother: or, consolidated, the figure of the mother in melodrama. Because it's Manuela's presence that seems to give away the artifice. Her entrance into the frame, the camera's focus on her, does not give space to the poster. But it is also the poster that threatens Manuela's hold over her son, precisely because it's big, because it's artificial. As we continue after the play, Esteban wants to get Huma's autograph. He and Manuela wait by the stage door. At her son's request, Manuela acquiesces to tell Esteban “all about [his] father.” Excitedly, joyously and lovingly he kisses Manuela on the cheek—but at that moment, Huma appears from backstage, the red of her name now fully apparent in her vibrant hair. How can Manuela compete with this red? She grips her son's arm, as if to hold him in place, but he runs to Huma's car. Through the window, they stare at one another, and the car drives off. Huma turns, peers through the back window. Her eyes (those eyes—to say nothing of those lips) appear clear through the pouring rain. Beacons whose pull is irresistable to Esteban, and so he takes off after them.

The camera pulls away from Manuela, but whose perspective is this? Is this the final glance back that Esteban never gave to his mother? Or is this Huma's perspective from the car? Is it Manuela she's been looking at? Both and neither: the camera communicates from its own 'perspective'. First an avenue for interrogation (possessing a certain skepticism, a sentience or awareness), it now enters into a realm of emotion. It emotes: pulling away from Manuela, it focuses on her, sympathizes with her. That move is, to me, nothing short of heartbreaking. Almadovar's style, the style of melodrama, is so much about form, not content, as the communicator of emotion.

We switch then into Esteban's POV as he's hit; the camera spins, twirls, lands on the ground, and we get the final image, sideways on the wet pavement, of Manuela, her son now truly gone from her grasp, running to him.

What was Esteban seeking? Huma is the objet petit a, yes, but I think it's actually performance he's seeking. That is the unattainable object of desire. Esteban seeks the performance in (and of) life (his mother acting in her youth, and now, simulating the transplant situations). Huma is simply the manifestation of that desire. So it makes sense that Esteban seems to be writing this film, that he's Almadovar's alterego, and that his death represents a passing into narrative: Manuela sets off to find Esteban's father, to fulfill her promise to tell “all about [his] father.” (Note, though, that immediately after Esteban dies, he passes into voice over, a sort of ghostly presence that comes from 'behind' the camera.)

The awareness that we see in the opening minutes of Todo sobre mi madre is not the awareness of the post-modernist, ever distant, ever desiring to expose artifices; not really. It is instead an awareness that emotion is in construction and form. Melodrama is a genre whose tropes are so familiar and so transparent to us, but it's a genre whose form acknowledges and delights in these transparencies, these fictions and performances, and presents them as though they weren't transparent at all, as though they were every bit as real. The argument laid out in these first twenty minutes is an argument for the validity of artifice as a window into experience. Think of Agrado's speech about her various cosmetic surgeries. Or of Manuela, crying in the performance of A Streetcar Named Desire because of Stella, because she's lived Stella's life. Almadovar encacts, here, the vicarious experiences that melodrama (and fiction in general) offer to us: the “experience of suffering,” as David Foster Wallace said, that brings us to art. An experience that may be impossible in reality, but on which reality desperately depends.

[Look at Ryland's companion image essay.]

First, sorry, Mark, it's taken me so long to comment. In a way, my image essay was like a comment, though, right?

ReplyDeleteI think you're off to a great start. This is a good launching pad of a movie for our twin interests in melodrama and its significance. I really dig your interest in looking, too. How looking is becoming, is life; how the world is made of images. This is something I like to think about. I'm also into the idea of performance, or good acting, as in acting in the world, as the object of desire. This seems to be a recurrent problem. Almost every melodrama is a question of style: how to be/act/live in the world.

What's cool about Pedro is he sees this as a ripe opportunity to live a full, engaged life. Even in the face of terrible happenings. The world is malleable in his Spain. There's a lot of agency.

Can't wait for the next installment!