by Ryland Walker Knight

—We just recycle is allWe all carry a list, some even write lists down, to remember what to watch or to read or to eat or to buy or to accomplish. But, come on, let's face it: lists are easy. And, at this moment, do you really need another list? To answer, sort of, Danny and I decided to chuck the list, mostly, to try to winnow this year's year-end wrap up in The Notebook. Today starts this new cycle in

this Part I post. As we wrote over there, we switched styles and asked contributors to pair a new film (theatrical, festival, whatever barometer) with an old film (rep house, disc, you pick) seen this year. I felt mine was pretty obvious, but, nonetheless, it's easily a dream double bill I'd love to sit with in a theatre:

36 vues du Pic Saint Loup (Jacques Rivette, 2009) +

The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1953). I say more in the post, which you'll have to read

over there, and I even propose a few other pairings. But I wrote that copy a little while ago. And, per the rules, my minimal commentary for my secondary double bills couldn't be used. So I decided not only to propose another, sixth double bill in this dedicated link-thru but also give you my complete list of double bills complete with the themes (jokes) I see emerging from those pairs:

- 36 vues du Pic Saint Loup (Jacques Rivette, 2009) + The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1953) — Wear your smile not your hurt

- The Informant! (Steven Soderbergh, USA) + Ordet (Carl Theodore Dreyer, 1955) — Telling stories to ourselves

- Fantastic Mr. Fox (Wes Anderson, USA) + Monkey Business (Howard Hawks, 1953) — Run a ring around the egos

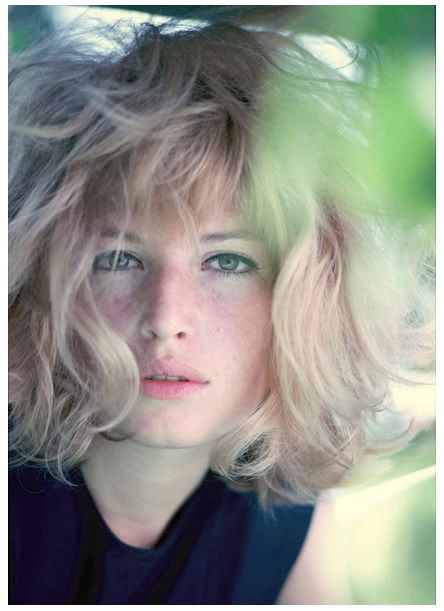

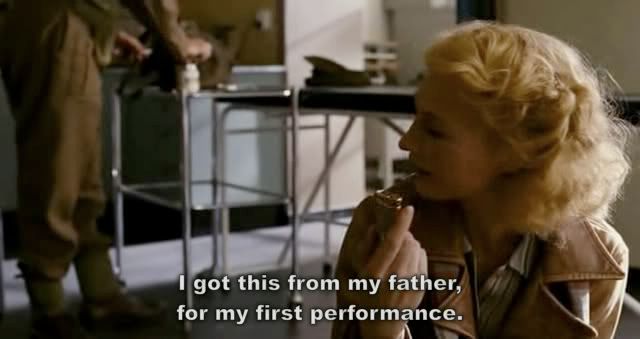

- La frontiere de l'aube (Philippe Garrel, France) + Bonjour Tristesse (Otto Preminger, 1958) — Ghosts

- 35 rhums (Claire Denis, France) + Le garçu (Maurice Pialat, 1995) — Dads

- Inglourious Basterds (Quentin Tarantino, USA) + A Canterbury Tale (Powell & Pressburger, 1944) — There's a war on?

- Inglourious Basterds + Black Book (Paul Verhoeven, 2006) — Pulp fiction [see below]

———

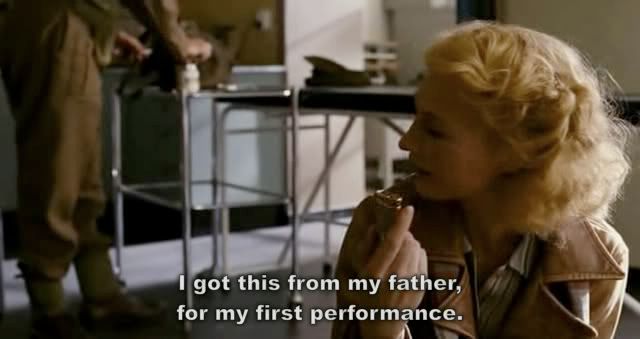

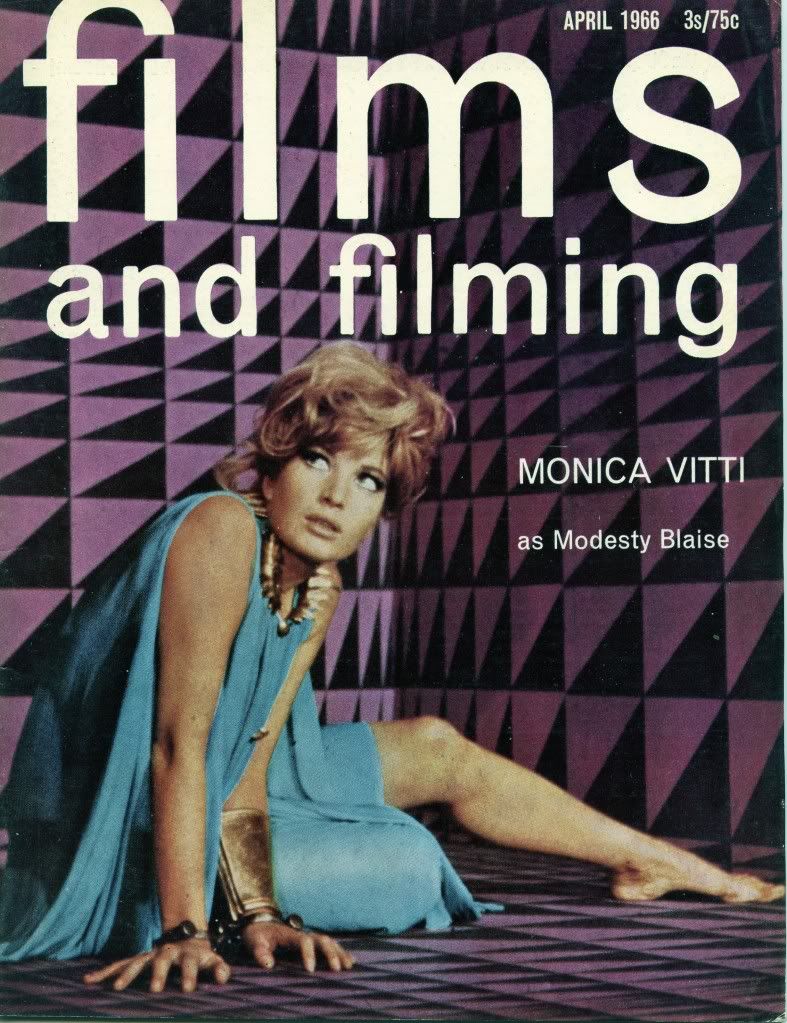

Last week I finally saw Paul Verhoeven's 2006 feature,

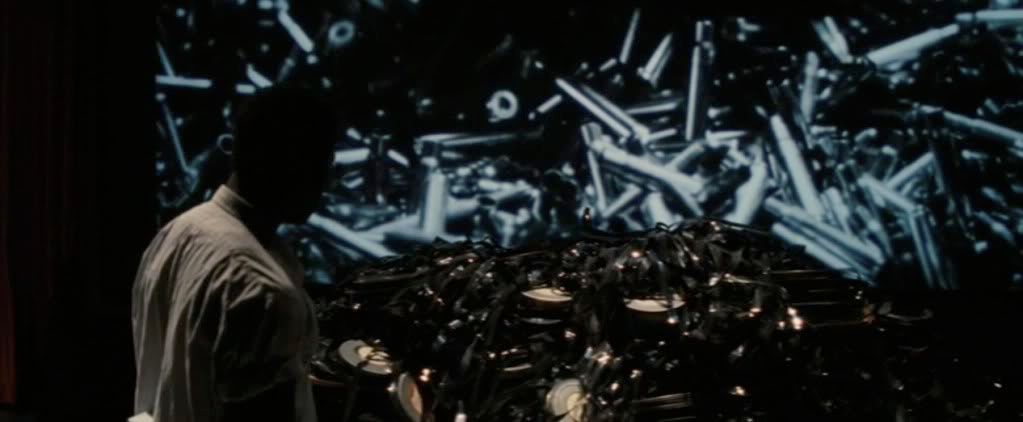

Black Book, and it quickly catapulted up my favorites list. In fact, I watched it twice—and the second time I made my own double bill, pairing it with

Inglourious Basterds. This is another slightly obvious double bill, but the films are such different modes, and actually such different postures, that, seen back-to-back with plenty of snacks, the pairing was rather illuminating beyond the World War II "settings" we're given.

Verhoeven's less a formal master than Tarantino (whose stylistic evolution since 1994 is significant, though also almost subtle in that its tied to his editing patterns, which is inextricable from his obsession with talk), but the Dane's film is no less stylistic or dashing or conceptual. Indeed,

Black Book is arguably

freer, and

more dashing, though it is also the more circumscribed, the more "factual" and "representational"—even, I'd say, more narrative—film. The power of

Black Book is precisely that it fuses into both a conceptually stimulating and a plain entertaining master work. Verhoeven's film throws up action scenes galore, yes, and a compelling revenge yarn, to say nothing of its bald prurience (yet), and hosts one of the best performances of the decade, easy, from Carice Van Houten. In short, though it's got some bitter pill stuff, it's a fun flick.

The real rub remains that both these films are pulp objects, mash-ups maybe, of infinite sources. Tarantino makes it more obvious, of course, with direct visual quotes and a few more names dropped, but the movies motivate Verhoeven in equal measure. However, Verhoeven's not a metabolic function the way Tarantino is: Verhoeven simply

uses the movies, and nods at symbols while making his own; Taratino, on the other hand, shows his hand constantly. For instance,

Black Book cat calls

Mata Hari in a tossed off line of dialogue, to remind us of another reason both culturally specific at the time and cinephilliacly tickling now why this Jew went blonde, while

Basterds punctuates its first major scene with as big a "quote" as possible, lifting Ford's doorway from

The Searchers (and others) to plant it in a southern France pastoral of 1941. In fact, nearly everything in

Basterds is a quote or in quotes—especially the actors—unlike

Black Book, always a

cynical horrorshow, which aims to eschew all trickery just as soon as the world allows.

Which is to say that, since Tarantino the American is obsessed with charisma and Verhoeven the Euro is obsessed with sex, one film is built on rep and one film is built on bait (respectively). In fact, everybody in

Basterds is obsessed with their rep, forever asking "What have you heard of me?" while all of

Black Book is premised on Carice's undeniable appeal, her nudity not a tease so much as a fact of the world—men go dumb and forsake themselves for such a small cost/price.

These postures, too, help define the films' attitudes towards history. Tarantino's out to earn the right to write it as he sees fit, as if by sheer force of talent he gets that honor. Verhoeven's out to simply write a story, to given face to a certain strand, to show you how history is, in fact, written not by the winners but rather by the survivors. Further, Tarantino closes his own film off, burns it to the ground and seals it in its own skin-tomb, while Verhoeven leaves his open to scramble, its final tableau a design of perpetual defense. You get the sense that

Black Book, though it's putatively inspired by true events, is a fiction invented to talk about a moment in history rather than a document, of sorts, about how some Jews fought their cultural legacy. It's that fantastic. On the flip side, it's easy to see

Basterds as a-political, a complete reverie of light and dark, blood and guts, everything celluloid can capture. The trick to the double bill, if you want to have a really good time, is obvious: you save the fantasy for second. You still won't get out alive, but you might smile more while trying.

———

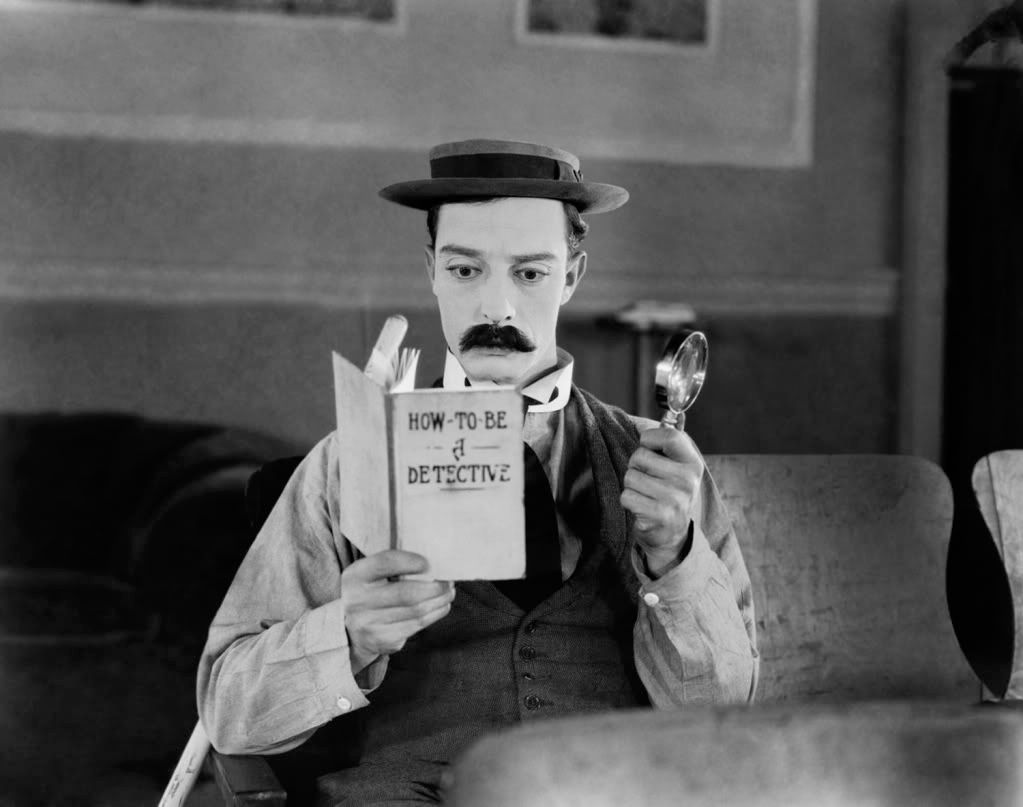

I should also say, watch the

Metro Classics blog for a quick top five comedies of the decade from yours truly. I only played along because I miss those dudes, and I thought that'd be a fun way to participate. Otherwise, I have no time for that kind of thing. Plus, I like to advocate for comedy. A great comedy is rarer these daze, but, believe me, although it might appear different from an "objective" angle on the films I often laud, a great comedy will most often trump a great tragedy in my book.

What might get this list into trouble with some of you, as it has with the friends I've shared it with, is how I define "comedy." For me, it's still a structural classification as much as "did it make me laugh?" If it ends well, with a marriage or something like one, then it's probably a comedy. However, there are black comedies, too, which flip that necessity around past tragedy. The Coens are great at this: their brand of comedy is often of the "what else can we do?" variety. You either laugh or you die. Actually, you'll die either way, but at least you can die laughing. It's nihilism, yes, but not everybody can be Wes Anderson or Arnaud Desplechin. And nobody, I mean it, nobody's Jean Renoir.

———

—Laugh a little.