We weren't even going to talk to you!

Spend some time with the boys. They're smashed on life.

Open your eyes, your ears, your nostrils: the weight is over.

Spend some time with the boys. They're smashed on life.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

11:37 AM

3

grooves

![]()

Labels: blogging, Cassavetes, conversation, Dick Cavett, integrity, juggling, rwk, youtube

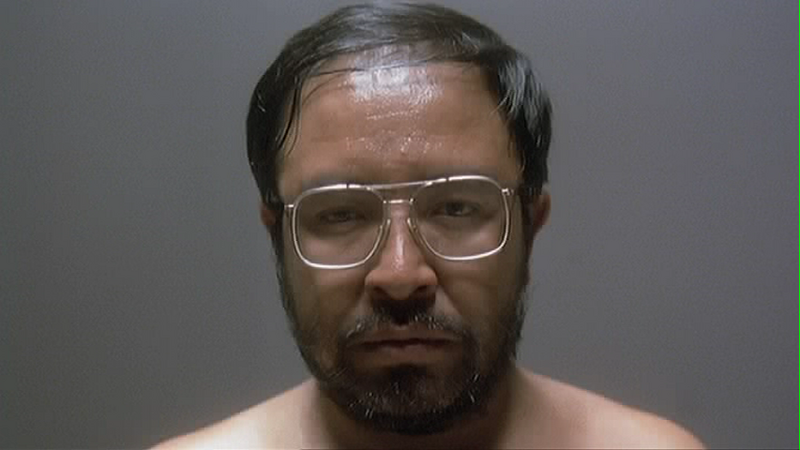

For instance, I'm taking a course called "The Action Film." It's a ton of fun. The filmography is packed with cool movies and we get to watch them in a big room on campus complete with powerful surround sound that was built in honor of the man who started UC Berkeley's Film department. Last week we watched John Woo's Hard Boiled. It was perhaps the most riotous screening yet, which is saying something a week after jailbird McTiernan's Predator. I thought I might try to write about that close-up at the end of the first firefight, where Chow Yun Fat gets blood splattered all over his flour-covered white face after he shoots a dude in the face at close range. It's a shocking moment and my classmates sure did jump. What's cool about it, though, is it's just another moment for Woo to color his melodrama. It's really no different from how Pedro Almodovar shoots a lot of Matador, which is also after the melodrama of classic Hollywood (like Sirk, like Duel in the Sun). But a whole essay seemed too much.

For instance, I'm taking a course called "The Action Film." It's a ton of fun. The filmography is packed with cool movies and we get to watch them in a big room on campus complete with powerful surround sound that was built in honor of the man who started UC Berkeley's Film department. Last week we watched John Woo's Hard Boiled. It was perhaps the most riotous screening yet, which is saying something a week after jailbird McTiernan's Predator. I thought I might try to write about that close-up at the end of the first firefight, where Chow Yun Fat gets blood splattered all over his flour-covered white face after he shoots a dude in the face at close range. It's a shocking moment and my classmates sure did jump. What's cool about it, though, is it's just another moment for Woo to color his melodrama. It's really no different from how Pedro Almodovar shoots a lot of Matador, which is also after the melodrama of classic Hollywood (like Sirk, like Duel in the Sun). But a whole essay seemed too much.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

11:58 AM

3

grooves

![]()

Labels: beauty, blog-a-thon, blogging, Carlos Reygadas, Claire Denis, Kieslowski, reflection, rwk, screenshot, The House, The New World, Wes Anderson, Ziyi Zhang

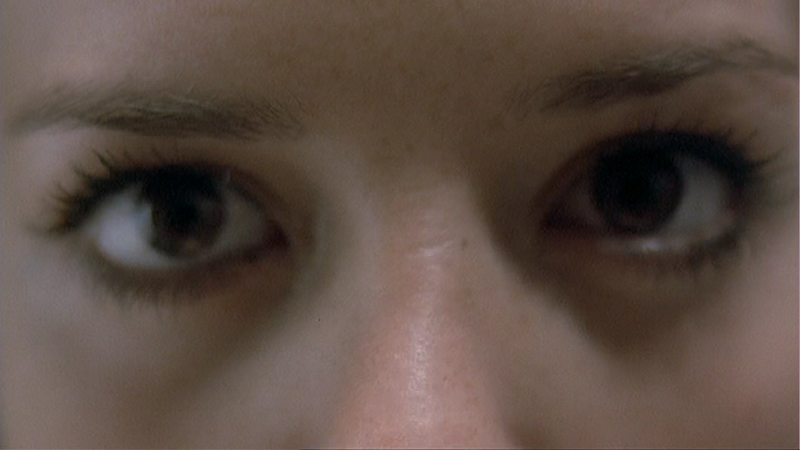

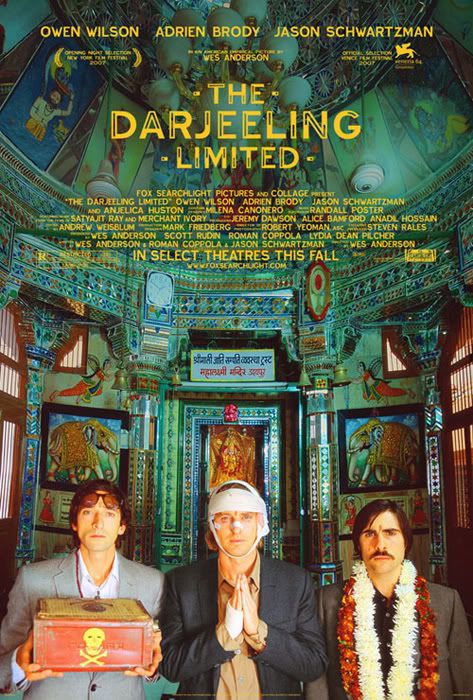

What I find most frustrating reading negative reviews of the picture is that each writer of such essays seems determined not to enjoy him or herself. Which is not to say I prize an essay where it's all about the writer and his or her reaction to the film. Rather, I wish more writers spent a little more time reflecting upon their reactions in as generous a manner as possible. Suppose there might be a reason, within the rubric of the film, that Wes Anderson choses to shoot scenes the way he does. Where the hell is this odd, almost-fish-eyed camera? Is it a point-of-view? Is it not? What's with all the tacky zooms? Why is the camera moving laterally, or panning 180, or 360, degrees? Why all this slow-motion? Why is the camera everything? The easiest answer to that summation-question would be: the camera is not a tool, really, for Wes Anderson, but another set of eyes. What complicates this notion is how we in the audience are continually confronted in Darjeeling by the eyes of the characters: the camera becomes not just another set of Wes-eys but, at the same time, audience-eyes. You there in your seat -- yeah, you -- you're here, too, onscreen (and in the page) -- you are at once audience member, brother, absent father, absent mother, a businessman, a girlfriend, a wife, a steward, a man-eating tiger. And, to echo something I've written before, they are all happening, always (and already).

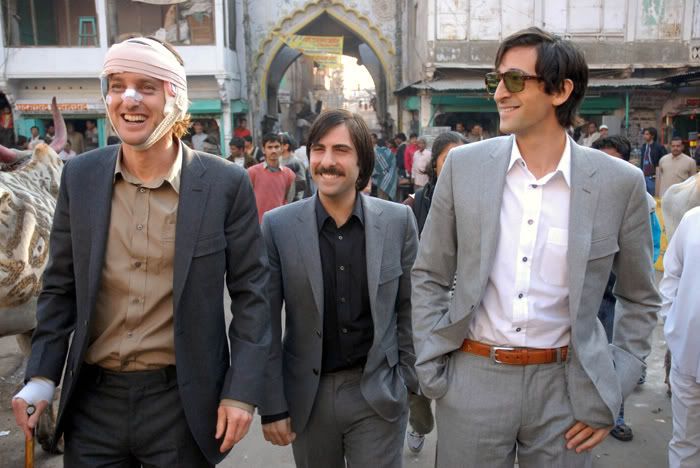

What I find most frustrating reading negative reviews of the picture is that each writer of such essays seems determined not to enjoy him or herself. Which is not to say I prize an essay where it's all about the writer and his or her reaction to the film. Rather, I wish more writers spent a little more time reflecting upon their reactions in as generous a manner as possible. Suppose there might be a reason, within the rubric of the film, that Wes Anderson choses to shoot scenes the way he does. Where the hell is this odd, almost-fish-eyed camera? Is it a point-of-view? Is it not? What's with all the tacky zooms? Why is the camera moving laterally, or panning 180, or 360, degrees? Why all this slow-motion? Why is the camera everything? The easiest answer to that summation-question would be: the camera is not a tool, really, for Wes Anderson, but another set of eyes. What complicates this notion is how we in the audience are continually confronted in Darjeeling by the eyes of the characters: the camera becomes not just another set of Wes-eys but, at the same time, audience-eyes. You there in your seat -- yeah, you -- you're here, too, onscreen (and in the page) -- you are at once audience member, brother, absent father, absent mother, a businessman, a girlfriend, a wife, a steward, a man-eating tiger. And, to echo something I've written before, they are all happening, always (and already). Adrien Brody's look across Jason Schwartzman at Owen Wilson (as brothers Peter, Jack and Francis Whitman) triggers a memory, which is a mini-movie unto itself, wrapped up inside the bigger, whole movie. We know from earlier in the film that this memory also serves as material for a short story Schwartzman's Jack has written, and shown to Peter, about the day of their father's funeral. Later, Jack will read to his brothers the ending of a new short story he has begun writing, without knowing the beginning; the lines of dialogue are direct quotes from Darjeeling's companion "Part 1" film, Hotel Chevalier. Jack insists throughout that all his characters are fictional until this moment, when he accepts his brother's compliment (Peter says he likes how mean Jack is in the story), which is more validation than if they simply said it was well written, as Francis does earlier.

Adrien Brody's look across Jason Schwartzman at Owen Wilson (as brothers Peter, Jack and Francis Whitman) triggers a memory, which is a mini-movie unto itself, wrapped up inside the bigger, whole movie. We know from earlier in the film that this memory also serves as material for a short story Schwartzman's Jack has written, and shown to Peter, about the day of their father's funeral. Later, Jack will read to his brothers the ending of a new short story he has begun writing, without knowing the beginning; the lines of dialogue are direct quotes from Darjeeling's companion "Part 1" film, Hotel Chevalier. Jack insists throughout that all his characters are fictional until this moment, when he accepts his brother's compliment (Peter says he likes how mean Jack is in the story), which is more validation than if they simply said it was well written, as Francis does earlier.

This movie is as much, if not more, about the construction of fictions as it is about its ostensible plot. Wilson's Francis, trying to put his life back together after a suicide attempt, constructs the India trip, with its laminated itineraries, as a potential happy ending to his family saga. Brody's Peter seeks a continuance of the narrative of his late father (the last time the brothers all saw each other was at his funeral) by furtively, obsessively, hanging on to the patriarch's old possessions. Schwartzman's Jack is a writer of short stories — stories he insists are "entirely fictional." Much of the film's subtext is devoted to both peeling away and reinforcing that claim.

But The Darjeeling Limited is as much about fiction as it is about family. That it succeeds so well and so slyly even while dealing with these topics in its own stylish but unsparing way is reason for moviegoers to rejoice.

Of course, this quote echoes a few things for me, including my own dealings with Wes Anderson's beguiling, and delightful, films. I think you can make this argument about storytelling with any of his films: it is as major a theme as family or death or theatricality are for Anderson. Think of Dignan's fiction about Mr. Henry, and vice-versa. Or Max Fischer's dad-as-doctor lie. Or all the books in The Royal Tenenbaums. Or, hell, all of The Life Aquatic and its constant movie set setting. Think of his TV ads. Think of how Schwartzman prepares his room for Natalie Portman's entrance in Hotel Chevalier. The effectiveness of these offerings, while propelled more by dialogue than visuals the earlier you go in his filmography, is tied, at least partially, into how Anderson uses his camera. He's not making a representation of a world -- he makes the world as he would have it, as a movie. (No d'uh, right?) Complaints about his films as contrived are as wrong-headed as can be: to invent a fiction, in any medium, is a contrivance, an artifice from the get-go. To tether it to some kind of “reality” is a limitation not of scope or imagination (that's tough work to make "real" humanist stories) but of understanding.

Of course, this quote echoes a few things for me, including my own dealings with Wes Anderson's beguiling, and delightful, films. I think you can make this argument about storytelling with any of his films: it is as major a theme as family or death or theatricality are for Anderson. Think of Dignan's fiction about Mr. Henry, and vice-versa. Or Max Fischer's dad-as-doctor lie. Or all the books in The Royal Tenenbaums. Or, hell, all of The Life Aquatic and its constant movie set setting. Think of his TV ads. Think of how Schwartzman prepares his room for Natalie Portman's entrance in Hotel Chevalier. The effectiveness of these offerings, while propelled more by dialogue than visuals the earlier you go in his filmography, is tied, at least partially, into how Anderson uses his camera. He's not making a representation of a world -- he makes the world as he would have it, as a movie. (No d'uh, right?) Complaints about his films as contrived are as wrong-headed as can be: to invent a fiction, in any medium, is a contrivance, an artifice from the get-go. To tether it to some kind of “reality” is a limitation not of scope or imagination (that's tough work to make "real" humanist stories) but of understanding.  (This is similar to what makes Werner Herzog so interesting: he does not delineate between "fiction" and "non-fiction" films. He simply makes films. He understands that even a "documentary" is a fiction. It has its own rules, sure, but the documentary in Herzog's hands is not about actually documenting the events. In The White Diamond, maybe his greatest film, he does not show the balloon when it is first dubbed such, he lets a man sitting on an inflatable chair smoking a joint call it a “white diamond.” A lesser filmmaker would have cut immediately to the balloon. Herzog simply holds on the man as he soaks in the scene. The fiction of the object is as important as the object itself.)

(This is similar to what makes Werner Herzog so interesting: he does not delineate between "fiction" and "non-fiction" films. He simply makes films. He understands that even a "documentary" is a fiction. It has its own rules, sure, but the documentary in Herzog's hands is not about actually documenting the events. In The White Diamond, maybe his greatest film, he does not show the balloon when it is first dubbed such, he lets a man sitting on an inflatable chair smoking a joint call it a “white diamond.” A lesser filmmaker would have cut immediately to the balloon. Herzog simply holds on the man as he soaks in the scene. The fiction of the object is as important as the object itself.)

No, the camera's not the whole show, but the objects and Anderson's dollhouse placement of them are largely about "subjectivity" as well. Critics have already sucked their teeth at the literal "baggage" that trails the brothers everywhere they go. Well, the obviousness that they're so up in arms about is what fleshes these characters out. The props and bric-a-brac convey plot/character/backstory nuggets (like Bill Murray's family portrait in Rushmore) not just for efficiency's sake. They trouble and redirect some of our less charitable tendencies. Wes has a crucial understanding about people: We size each other up, from head to toe, mercilessly. We make instant judgments. Ry, you mention that he makes his own worlds. Yes, and in his worlds, people are exactly what they wear, eat, carry or cast off. It's plain to see who's up to what in Wesworld, even though the characters are mostly flying blind as if they're in our prismatic, deceitful world. (And, of course, psychologically, they are.) Owen's bandages, Schwartzman's cheesy ‘stache and Brody's shades tell us up front what these guys are dealing with. Their journey in the film is toward seeing each other the way Anderson presents them to us -- as lost boys.

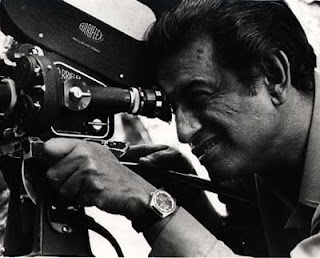

No, the camera's not the whole show, but the objects and Anderson's dollhouse placement of them are largely about "subjectivity" as well. Critics have already sucked their teeth at the literal "baggage" that trails the brothers everywhere they go. Well, the obviousness that they're so up in arms about is what fleshes these characters out. The props and bric-a-brac convey plot/character/backstory nuggets (like Bill Murray's family portrait in Rushmore) not just for efficiency's sake. They trouble and redirect some of our less charitable tendencies. Wes has a crucial understanding about people: We size each other up, from head to toe, mercilessly. We make instant judgments. Ry, you mention that he makes his own worlds. Yes, and in his worlds, people are exactly what they wear, eat, carry or cast off. It's plain to see who's up to what in Wesworld, even though the characters are mostly flying blind as if they're in our prismatic, deceitful world. (And, of course, psychologically, they are.) Owen's bandages, Schwartzman's cheesy ‘stache and Brody's shades tell us up front what these guys are dealing with. Their journey in the film is toward seeing each other the way Anderson presents them to us -- as lost boys. Which brings me to Satyajit Ray. You haven't seen too much (or any?) of his stuff, and it is absolutely not necessary for blissing out on this flick. But having watched Ray's Apu trilogy as many times as you are bound to see Darjeeling, I can say that Ray is Mr. Power and Grace. Anderson pays him tribute throughout this film, mostly by using film music composed by Ray and Ravi Shankar. However, the scene where the brothers take a whiff of the perfume and the joke about trains in the distance will both become even prettier when you see how affectionately they bow to Ray. I can't wait to send you these Apu films, along with his Devi, from 1960. I'm in the middle of that one right now, and it has all the rapture of that overhead baby shot in Darjeeling--arguably--no, no argument here: In-damn-disputably the most wondrous shot of an infant ever presented in a film. Those feet in the margins of the frame.

Which brings me to Satyajit Ray. You haven't seen too much (or any?) of his stuff, and it is absolutely not necessary for blissing out on this flick. But having watched Ray's Apu trilogy as many times as you are bound to see Darjeeling, I can say that Ray is Mr. Power and Grace. Anderson pays him tribute throughout this film, mostly by using film music composed by Ray and Ravi Shankar. However, the scene where the brothers take a whiff of the perfume and the joke about trains in the distance will both become even prettier when you see how affectionately they bow to Ray. I can't wait to send you these Apu films, along with his Devi, from 1960. I'm in the middle of that one right now, and it has all the rapture of that overhead baby shot in Darjeeling--arguably--no, no argument here: In-damn-disputably the most wondrous shot of an infant ever presented in a film. Those feet in the margins of the frame.

It's hard to approach a new film by Wes Anderson without feeling like you've walked into an argument. There's something about his dollhouse aesthetic, his storybook formality, his miniaturist's attention to detail and his dogged belief in the power of objects to elicit the most oblique and recondite emotions that seriously sets people off. Why is a question for another paragraph, but needless to say it's exactly this staunch commitment to artificiality that makes his work what it is.

In addition to the surface-as-essence approach to dressing characters and scenes in Wesworld, there's something about how that subjective camera shoots those objects that imbues them with character. How things are arranged, perhaps staged, to echo myself again, matters, because this new film, like all his others, is still “cluttered” with detail, for all its acclaimed “maturity” (from its supporters). How the details accrue in the picture is probably a good indicator of how Wes “clears the tightrope” of storytelling. As a practice, storytelling relies on affective details that trigger a response. If we can agree that art is about life, why shouldn't something this artful (and artificial) be as resonant as a piece of art that is artful in its artlessness? Is it just a matter of taste at that point? To argue aesthetics seems a silly dead end, especially since I don't know much about it outside thinking, “Well, that sure is pretty and it looks like it was a thoughtful choice -- on the part of the artist and consistent with the rest of the work of art.” Plus, “aesthetics” is such a broad topic to whittle down to film style. We can table that. What I'm curious about is why Wes Anderson's rhetoric ticks people off. Because I can eat it all day. His world is full of things. Even in slow motion the world is alive with motion and speed.

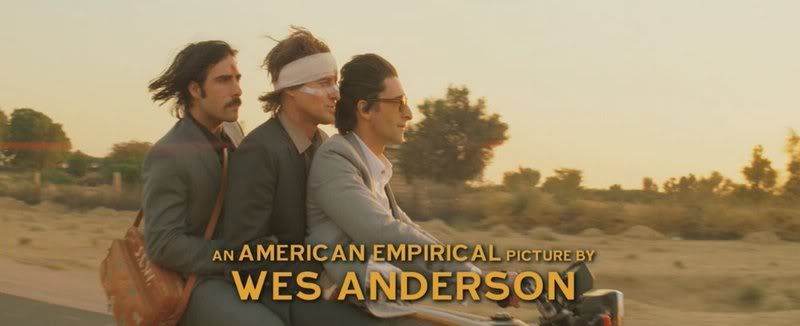

In addition to the surface-as-essence approach to dressing characters and scenes in Wesworld, there's something about how that subjective camera shoots those objects that imbues them with character. How things are arranged, perhaps staged, to echo myself again, matters, because this new film, like all his others, is still “cluttered” with detail, for all its acclaimed “maturity” (from its supporters). How the details accrue in the picture is probably a good indicator of how Wes “clears the tightrope” of storytelling. As a practice, storytelling relies on affective details that trigger a response. If we can agree that art is about life, why shouldn't something this artful (and artificial) be as resonant as a piece of art that is artful in its artlessness? Is it just a matter of taste at that point? To argue aesthetics seems a silly dead end, especially since I don't know much about it outside thinking, “Well, that sure is pretty and it looks like it was a thoughtful choice -- on the part of the artist and consistent with the rest of the work of art.” Plus, “aesthetics” is such a broad topic to whittle down to film style. We can table that. What I'm curious about is why Wes Anderson's rhetoric ticks people off. Because I can eat it all day. His world is full of things. Even in slow motion the world is alive with motion and speed.  The idea that objects (including people) can "elicit the most oblique and recondite emotions" in and of themselves and their appearance should be a delight, not something to harp on: it is an offering. Walking out of the film on Friday my friend said, “I feel like I've been given a thoughtful gift.” I think this kind of reaction is what Wes is aiming for in how he shoots objects with his camera. The objects carry history that can produce associations. Opening this film with Bill Murray's Businessman missing the train in slow motion, while a young man, Adrian Brody's Peter, runs past him, is not meant as an inciting incident in some kind of narrative but simply to trigger a response and tell you how things are arranged in this movie (this world): it's all about the train. The train is the name of the movie. The train is the movie. So when Bill Murray can't catch the train, Anderson is showing you, in as simple terms as possible, this movie is also all about youth.

The idea that objects (including people) can "elicit the most oblique and recondite emotions" in and of themselves and their appearance should be a delight, not something to harp on: it is an offering. Walking out of the film on Friday my friend said, “I feel like I've been given a thoughtful gift.” I think this kind of reaction is what Wes is aiming for in how he shoots objects with his camera. The objects carry history that can produce associations. Opening this film with Bill Murray's Businessman missing the train in slow motion, while a young man, Adrian Brody's Peter, runs past him, is not meant as an inciting incident in some kind of narrative but simply to trigger a response and tell you how things are arranged in this movie (this world): it's all about the train. The train is the name of the movie. The train is the movie. So when Bill Murray can't catch the train, Anderson is showing you, in as simple terms as possible, this movie is also all about youth.  That is, as much as a movie so fearful of death can be about youth, and vigor. When the brothers chuck their, ahem, luggage at the end (to catch the train), the act is not simply some metaphor about mourning sons finally getting rid of their fatherly baggage. Rather, the film is saying that it is more important to watch the movie (to catch the train) than to hold on to things; those things (or their ephemeral essence?) stay with you no matter what, forever. Owen Wilson's Francis says, “Dad's luggage isn't going to make it” and the three brothers smile, and they run faster. Just like his missing loafer, the luggage doesn't matter, in the end. Those things are just distractions anyways. This both calls attention to the objects and tells you not to get hung up on them.

That is, as much as a movie so fearful of death can be about youth, and vigor. When the brothers chuck their, ahem, luggage at the end (to catch the train), the act is not simply some metaphor about mourning sons finally getting rid of their fatherly baggage. Rather, the film is saying that it is more important to watch the movie (to catch the train) than to hold on to things; those things (or their ephemeral essence?) stay with you no matter what, forever. Owen Wilson's Francis says, “Dad's luggage isn't going to make it” and the three brothers smile, and they run faster. Just like his missing loafer, the luggage doesn't matter, in the end. Those things are just distractions anyways. This both calls attention to the objects and tells you not to get hung up on them.  I guess what I'm trying to say is: sure, you can read the scene as a blatant metaphor for “growth” or something but that belittles what happens, and the things that matter are those characters and their actions. Besides, the characters are still covered with details, they still carry a lot on their faces and bodies. And having seen them through a whole film with those suitcases and handbags you know that they're more mnemonics than anything. And if we understand that memories are forever inside us then we realize that we don't need mnemonic aids. (Think of the funeral within the funeral: lives within lives and stories within stories.)

I guess what I'm trying to say is: sure, you can read the scene as a blatant metaphor for “growth” or something but that belittles what happens, and the things that matter are those characters and their actions. Besides, the characters are still covered with details, they still carry a lot on their faces and bodies. And having seen them through a whole film with those suitcases and handbags you know that they're more mnemonics than anything. And if we understand that memories are forever inside us then we realize that we don't need mnemonic aids. (Think of the funeral within the funeral: lives within lives and stories within stories.) Still, Wes Anderson is of a tradition of filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino (or the French New Wave that so inspires both artists' work) that metabolize cinema. They take it up (all the time, from everywhere), digest it, and reproduce new films. This is perhaps most apparent in Darjeeling in the musical cues Anderson borrows from Satyajit Ray. (But the only reason I know that this music is from those films is because I was told ahead of time. I look forward to understanding the homage better, and I thank you for the offering.) What's funny is I can also understand the music as a signifier for this odd Western ideal of India the boys are seeking. The music in Wes Anderson is an object weighted with (and by) history as much as things like suitcases. Think of the British Invasion tunes, too: in a story about youthful brothers on a journey into the spiritual unknown, the first song with lyrics in the film is by The Kinks (a band comprised of brothers), called “This Time Tomorrow.” It's all about not knowing where the journey will take the passengers. The song, like Peter catching the train in slow motion, knows that to get anywhere you simply have to start going.

Still, Wes Anderson is of a tradition of filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino (or the French New Wave that so inspires both artists' work) that metabolize cinema. They take it up (all the time, from everywhere), digest it, and reproduce new films. This is perhaps most apparent in Darjeeling in the musical cues Anderson borrows from Satyajit Ray. (But the only reason I know that this music is from those films is because I was told ahead of time. I look forward to understanding the homage better, and I thank you for the offering.) What's funny is I can also understand the music as a signifier for this odd Western ideal of India the boys are seeking. The music in Wes Anderson is an object weighted with (and by) history as much as things like suitcases. Think of the British Invasion tunes, too: in a story about youthful brothers on a journey into the spiritual unknown, the first song with lyrics in the film is by The Kinks (a band comprised of brothers), called “This Time Tomorrow.” It's all about not knowing where the journey will take the passengers. The song, like Peter catching the train in slow motion, knows that to get anywhere you simply have to start going.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

11:26 AM

16

grooves

![]()

Labels: conversation, criticism, Darjeeling Limited, family, formalism, genre as medium, letters, philosophy, rhetoric, rwk, SB, Wes Anderson

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

9:19 AM

19

grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, blogging, Darjeeling Limited, rwk, screenshot, Wes Anderson

In the spirit of The Kingdom (joke) ...

An Army Corps on the March

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

With its cloud of skirmishers in advance,

With now the sound of a single shot snapping like a whip,

and now an irregular volley,

The swarming ranks press on and on, the dense brigades press on,

Gliterring dimly, toiling under the sun --- the dust-cover'd men,

In columns rise and fall to the undulations of the ground,

With artillery interspers'd --- the wheels rumble, the horses sweat,

As the army corps advances.

>>cb