Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

There is really no overcoming one's fascination with particulars.

[Hermeneutics] is not a method or system or theory or any position to be defended or advanced but exactly a context of argument about understanding -- a context whose boundaries are determined not by conceptual traditions, much less by school disciplines, but by the thing itself, that is, by the question of what it is that happens (what the practical consequences are) when we try to make sense of something. What sense this question will have for us, however, is determined by how we frame it, and there are multiple, intersecting, and conflicting frames. Hermeneutics, as I understand it, is this whole network of lines and angles on the question of verstehen.* There is no getting outside of this network and giving a comprehensive view of it, which is one reason why it is not easy to give a conceptually coherent account of what hermeneutics is.

-- Gerald L. Bruns, Hermeneutics Ancient & Modern

That, too, is what my understanding of rhetoric, as this department has taught me, is: a thorough inhabitation of, not simply engagement with, an argument. And, you know, knowing how to act accordingly. This applies to everything, not just reading texts, like living life. Should be a good seminar. (The title of this post comes from somewhere near the end of the introduction to Bruns' book, and the quote from somewhere earlier in the introduction.)

*understanding

Monday, January 28, 2008

The Monday Evening Wire. Just a Step Behind.

Episode 54, "Transitions"

The M.O. within city hall, which in turn trickles down to the schools and the police station and the Sun papers, is quite clear at this point: everyone needs to do "more with less." In The Wire's final, 10-episode season (one considerably shorter than the past four), the show itself has been forced to do this as well. The street though -- well, obviously -- doesn't work like those other institutions no matter how many parallels are drawn between them. I didn't pick up on this the first three episodes; in fact, I sort of saw the show creating this mantra for all aspects of Baltimore (including the streets). "More with less" really isn't the case always, as last night's episode revealed. Marlo and Joe are filthy rich, they have huge crews and, in a sense, run their shares of the city. Marlo is even trying to make his money get smaller. I don't mean to say the street is working in an opposite fashion as city hall, though, as that would be an equal parallel, just in the other direction. They are, simply, different. And I have to say that I'm feeling really rattled writing this (whether for purely personal reasons or, in fact, because of the show, I don't quite know). Snoop, leaning back on her car tapping a gun on her chin, as she stands over an elder co-op member shitting himself, tied up and crying, is such a horrible image, but it goes almost forgotten in the shadow of Marlo's close-up as he watches Joe's blown-out head fall to the table: wouch!

On the street, the popular phrase has been something like "Joe ain't Marlo" or "Marlo ain't like Joe." Last night, one of the few lines the resurrected Greek delivered said as much. The phrase is true, sure, but what sort of morality does it set up for the the show? Why did I feel so sad when Prop Joe closed his eyes, slightly trembling? Why do I get so excited to watch Omar catch a shotgun and say, "Sweet Jesus, I'ma work them!"? The questions are mainly rhetorical, but they do have answers. Suffice it to say, just raising these questions is a victory for the show itself. Prop Joe supplies drugs to the whole fucking city: Michael's mom (who shared in another devastating scene last night) and Bubbles suffer because of him; Joe is responsible for the corners, the killings, Dukie's family! There are no good guys on the street, Bodie included. As despicable as he is, Colicchio opens the show with a statement that rings true (at least after re-looking at this episode, more numbly), "fuck it, they're all dirty anyway."

On the street, the popular phrase has been something like "Joe ain't Marlo" or "Marlo ain't like Joe." Last night, one of the few lines the resurrected Greek delivered said as much. The phrase is true, sure, but what sort of morality does it set up for the the show? Why did I feel so sad when Prop Joe closed his eyes, slightly trembling? Why do I get so excited to watch Omar catch a shotgun and say, "Sweet Jesus, I'ma work them!"? The questions are mainly rhetorical, but they do have answers. Suffice it to say, just raising these questions is a victory for the show itself. Prop Joe supplies drugs to the whole fucking city: Michael's mom (who shared in another devastating scene last night) and Bubbles suffer because of him; Joe is responsible for the corners, the killings, Dukie's family! There are no good guys on the street, Bodie included. As despicable as he is, Colicchio opens the show with a statement that rings true (at least after re-looking at this episode, more numbly), "fuck it, they're all dirty anyway."  In an effort to not take on that sort of boring, narrator voice, which I so quickly and easily acquire when I start to summarize, I won't summarize, as it wouldn't do last night's (and hopefully the rest of the) episode(s) justice. The final scene saw Joe offer his final proposition, one that was not accepted -- not even acknowledged actually -- and that "means something," as he says himself. Marlo is sick of hearing people talk, Omar is sick of Marlo doing that, and Jimmy and Freamon are sick of all of it. "Transitions" was about doing, not planning. It was an episode about taking action, from the bottom up. Templeton is a hack, yes, but he's ready to work for the Sun, now that he knows he has to. Burrell was finally fired, Daniels promoted. Jimmy and Freamon got the body they needed, and they did what they had to with it, hoping (always hoping) to re-open their case on Marlo. Carver earned his title as sergeant, and had to make the sacrifices that that step up required.

In an effort to not take on that sort of boring, narrator voice, which I so quickly and easily acquire when I start to summarize, I won't summarize, as it wouldn't do last night's (and hopefully the rest of the) episode(s) justice. The final scene saw Joe offer his final proposition, one that was not accepted -- not even acknowledged actually -- and that "means something," as he says himself. Marlo is sick of hearing people talk, Omar is sick of Marlo doing that, and Jimmy and Freamon are sick of all of it. "Transitions" was about doing, not planning. It was an episode about taking action, from the bottom up. Templeton is a hack, yes, but he's ready to work for the Sun, now that he knows he has to. Burrell was finally fired, Daniels promoted. Jimmy and Freamon got the body they needed, and they did what they had to with it, hoping (always hoping) to re-open their case on Marlo. Carver earned his title as sergeant, and had to make the sacrifices that that step up required.And Kima set up a day with her ex, which allowed her to see her "nephew." (This is one aspect of the episode I do want kind of summarize though, as it was truly important). As Kima watched the young boy, who's family was slaughtered in front of him, stare lifelessly into a block of Legos, last season was somehow revisited. In that young boy we saw everything that The Wire tells us can be lost. In the classrooms last season, amongst all these kids, so many of them cute and bright, the touching scenes were the ones that portrayed them as purely children. Times when they had either been alleviated from the pressures of their socio-economic situation, or had simply forgotten, and they would smile and clown on each other. (Something like the Six Flags scenes last week, but even more effective because they were in a classroom when they were "supposed" to be). I thought, "Shit, this kid is gonna be another Omar," which is what I'm sure most people were thinking then, and throughout most of last season about various other students. But re-inserting that type of scene, which surely elicits those same types of emotions, in an episode where such an ugly killing (I thought last week's was tough) ended the episode, was especially affective. It made me want to call my little brother (of 12) and smile just as Kima did. The stripping away of all things fun, all things youthful, is the corners' most effective killing mechanism. The kids aren't kids, and haven't been for a long time. Shit, Marlo is young himself, but when Joe tells him Cheese was a fuck-up and that, "I always treated you as a son," Marlo effectively made clear what his childhood was like and the role the streets gave him: "I wasn't made to play the son."

While "Transitions" was a most fitting title for last night, I find it mostly scary that it wasn't (rather won't be) the title for the last episode of the season. This was a week, like most weeks I guess, where evil trumps good. What made this week different, though, is that there was a lot of good. Daniels and Carver (and, while dirty-ish, Freamon, too) are the policemen B-More needs. Alma, while entirely inexperienced, is an honest and ambitious writer, one that understands how a newspaper should work. And, as I just said above, Kima may re-unite with the family she never should have neglected. Most of the transitions, though, were ones that terrify people, changes that further kill an already dying Baltimore. Hopefully the last episode won't treat B-More like Marlo handled Joe. But it probably will. After all, its a good show.

"Buyer's market out there" --Templeton

Copy Cat: the magnetic cover

by Bryn Esplin

by Bryn Esplin

It’s impossible to read a review of Cat Power without laborious detail given to the troubled life of Chan Marshal, but often these biopic criticisms do nothing more than impose a familiar frame around the “unstable” artist, insisting on her new, successful recovery, and forcing the happy ending. This would be the death of Cat Power. Recovery is a nice thing; instability is beautiful.

The technology of Chan’s cover is premised on the very essence of language itself: it’s unstable, indeterminate, and yet perpetually communicable. Her cover is not an obliteration or disregard of the “authentic”; in fact, it necessarily relies on the recognizability of the original to form the new.

How?

Cat Power is a magnifier of the beautiful moment, the lyric that melts. Take her cover of “(I can’t get no) Satisfaction” from the first Covers: “But he can’t be a man cause he doesn’t smoke the same cigarettes as me.” I have heard the Rolling Stones version ten trillion times, but I had never heard that line before. It simply never existed before Chan sang it.

Walter Benjamin helps explain her strange phenomenon of magnification: By close-ups of the things around us, by focusing on hidden details of familiar objects, by exploring common place milieus under the ingenious guidance of [the new voice] it extends our comprehension of the necessities which rule our lives; on the other hand, it manages to assure us of an immense and unexpected field of action.

Instead of the song as a closed system, forever preserved in the aura of the original, Chan opens it up, delicately, unfolding each lyric. The familiar is new again. It’s uncanny. Jukebox

Jukebox operates under the same logic. Stripping "I Believe in You" (a cover from Slow Train Coming

) down to a single electric guitar shuffle, she distills the solitary substance of faith. With a sloven slide-guitar, she rides off into nowhere on the Highwaymen's "Silver Stallion," and she lulls Sinatra's "New York, New York" into a languorous, ominous ballad, lingering over some words, neglecting others.

Never afraid of her own medicine (perhaps a Judy Garland-esque cocktail) she dismantles and reconstructs her own songs, most notably 1998's "Metal Heart" and 2006’s “Could We.” But this is never egotistical, for the cover insists the I is always another.

Sure, Cat Power is unstable: It’s her weapon of choice.

Teeth: a square Venn-diagram tracking little overlap.

It was hard to tone down the review and not use words like "snatch" and "cootchie" but I did it. To read the middle school safe review, click here, and you will be redirected to The Daily Californian's website. The short of it: not quite the movie it wants to be. Not quite funny enough, and way too many dicks. That is, in relation to the zero vaginas (dentata'd or not) elsewhere (not) on screen. Still, the crowd I saw it with sure did lap/laugh it up. So, you might like it more than grumpy me. (Finally read some other reviews. Here's two I like, and seem to be in line with: Glenn Kenny is yet less enthused than me, but maybe funnier; Lauren Wissot has pretty much the same argument as me, and Odie in her comments thread.)

Sunday, January 27, 2008

Persepolis: Bio-Graph.

A few unfinished thoughts.

by Sanaz Yamin

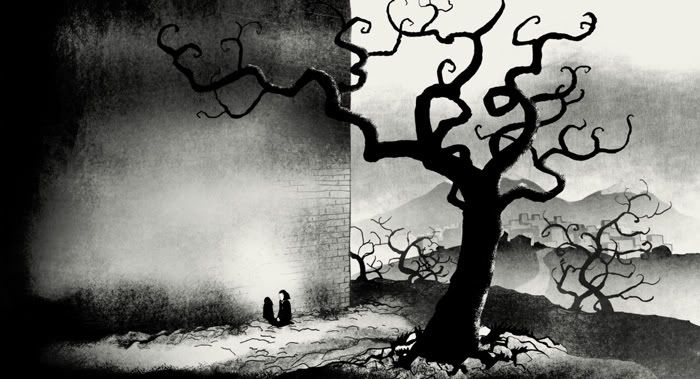

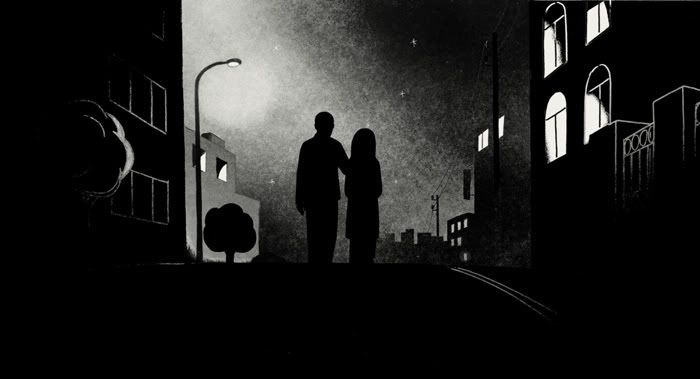

Persepolis is unlike other biographies that have come out recently (and a lot of them have) in that it is not only a creation of the life of the character, but simultaneously the film must argue for its own importance. Films like Walk the Line, Ray, and I’m Not There shamelessly rely on the popularity of the personality of the character. I'm Not There, for instance, pauses and zooms at the moment of a recognizable portrait contextualized. What was once one image, now is one in a series, transferring that interest in the portrait to one in the story of it in images. But why care about any image of Marjane Satrapi, much less an hour and a half of them? Persepolis has to answer that question.

This simultaneous introduction to and argument for the character is paralleled by the medium. Film captures and creates synchronically while drawing is diachronic. The why? of the image must be drawn with the film.

This simultaneous introduction to and argument for the character is paralleled by the medium. Film captures and creates synchronically while drawing is diachronic. The why? of the image must be drawn with the film.An immediate reason I believe Persepolis is worthwhile: it interprets a politically controversial country from a rarely presented point of view. Despite that Iran is news, it remains a mystery. Even I had much to learn from the history presented in the film, and I’m Iranian, so it can also be informative.

And then it’s also a great story, and it's beautiful. The black and white drawings highlight negative space in a way that only the best films can. The fades are not a curtain of black falling over the final image, but are the black from the image itself, seeping into the rest, or a zoom into the foreground, the passing of time or space between the images, therefore, is metonymic, as travel and time are to a life. I now wish I saw more color fades, a blue, red, green (i.e. Punch-Drunk Love), or even a picture -- not that pure black is not a picture in itself -- dissolving. But that's the whole point: blackness is still something, so why not choose a fitting something?

And then it’s also a great story, and it's beautiful. The black and white drawings highlight negative space in a way that only the best films can. The fades are not a curtain of black falling over the final image, but are the black from the image itself, seeping into the rest, or a zoom into the foreground, the passing of time or space between the images, therefore, is metonymic, as travel and time are to a life. I now wish I saw more color fades, a blue, red, green (i.e. Punch-Drunk Love), or even a picture -- not that pure black is not a picture in itself -- dissolving. But that's the whole point: blackness is still something, so why not choose a fitting something?Comments, criticisms, conversations welcome!

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Back to school 20:08 screenshot for the day.

From the 20:08 minute:second mark in Edward Yang's last film, the probably-perfect Yi Yi. Really would like to see some more of his films. Berkeley has a VHS copy of That Day, on the Beach. Guess I'll have to cross my fingers for that Cinematheque retrospective to travel West so I can see A Brighter Summer Day. My classes begin at 9:30 AM. Better get to bed. --RWK

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

12:02 AM

4

grooves

![]()

Labels: appreciation, blogging, Edward Yang, linkage, rwk, screenshot

Monday, January 21, 2008

Cloverfield targets the yuppies it loves.

It's kind of great that something like Cloverfield is a hit. Audacity is a strong card to play for me, I guess, and this new kind of monster movie J. J. Abrams delivered is pretty fucking audacious. If only it were a little better. How it could be any better I don't really know. Of course, the screenplay could use some work (re-jigger the trite love story, the inane running commentary, and the almost-idiot plot), and they could have cast some better actors (although it would be hard to find more attractive leads; notice the wise choice to keep Hud off-camera for most of the movie), but this is what we got. This 80-minute digicam movie about holding onto love even when there's a big ugly monster killing the city that the pretty little people populate. No, this isn't The Host or Jaws -- nor is it There Will Be Blood (looking at you, Ryland) -- but, really, what is? Is this movie truly worth hating? I don't think so. It's too weird. Sitting in a packed audience over the weekend, I couldn't believe this thing was actually making a lot of money: its handycam shake borders on unwatchable, the totally fuckable cast (thanks, Nathan Lee) is serviceable at its best, and I could totally see why it might give people a headache. That is if I wasn't so interested and involved in the movie the whole time I was watching it unfold.

The beginning is precious enough, and kind of longish, since there's only 80 minutes of movie, but both Michael Stahl-David (as the ostensible hero, Rob) and Odette Yustman (as the damsel-in-distress, Beth) are so good looking that I didn't quite care. The next part, with Rob's brother Jason (Mike Vogel) and his girlfriend, Lily (Jessica Lucas), starts out obnoxious since Jason can't work the camera, and it doesn't get much better once he hands off documentary duties to Hud (T. J. Miller), until the monster shit (like the head of The Statue of Liberty) hits the fan and starts flying down the streets. Then these yuppies start getting what they deserve. I mean, right? Get over yourselves! I hope to live in one of those kinds of amazing downtown loft-type apartments -- I'd love it, yes -- but I hope even more to never get that hung up on bullshit "love affairs" interfering with my professional life. You just deal with shit. I guess that's part of the point the movie is trying to make but with so much time and affection devoted to this young non-couple's not-quite-unrequited love (I'm talking Rob and Beth) it's hard to ignore that Cloverfield is definitely targeted at yuppies the same way it's out to kill yuppies. Like most aspects of the movie, it's a mixed bag.

The beginning is precious enough, and kind of longish, since there's only 80 minutes of movie, but both Michael Stahl-David (as the ostensible hero, Rob) and Odette Yustman (as the damsel-in-distress, Beth) are so good looking that I didn't quite care. The next part, with Rob's brother Jason (Mike Vogel) and his girlfriend, Lily (Jessica Lucas), starts out obnoxious since Jason can't work the camera, and it doesn't get much better once he hands off documentary duties to Hud (T. J. Miller), until the monster shit (like the head of The Statue of Liberty) hits the fan and starts flying down the streets. Then these yuppies start getting what they deserve. I mean, right? Get over yourselves! I hope to live in one of those kinds of amazing downtown loft-type apartments -- I'd love it, yes -- but I hope even more to never get that hung up on bullshit "love affairs" interfering with my professional life. You just deal with shit. I guess that's part of the point the movie is trying to make but with so much time and affection devoted to this young non-couple's not-quite-unrequited love (I'm talking Rob and Beth) it's hard to ignore that Cloverfield is definitely targeted at yuppies the same way it's out to kill yuppies. Like most aspects of the movie, it's a mixed bag. The coolest thing about Cloverfield is probably that, despite itself, I sat not apoplectic and bewildered but jazzed up and ready since I was so caught up with the idea that a monster movie was made like this. Okay, The Blair Witch Project did it first, I guess, and I like that it was a hit, but this one is a real big time movie, with one of those genius hype-generating marketing campaigns. (Okay, its marketing was kind of a rip off of the Blair Witch internet craze, too.) But, anyways, Cloverfield made a ton of money this weekend and it's a weird, not-typical Hollywood movie. Even The Bourne Ultimatum isn't this wobbly. I don't really know anything about avant-garde cinema but that late auto-focus fidgeting in the grass may be one of the coolest/weirdest things in a blockbuster I've seen in a while. Starting here of all places I can start to see why Cloverfield is different than Blair Witch: the camera is just another witness here, instead of some kind of agency device. It's also the reason it's a pretty muddled movie. For all the silly humanism in the stupid love story, the filmmaking itself isn't really interested in humans. It's a document --some weird artifact the government found? -- of human kind's idiot notion that they should win any and every battle because they can love. But love doesn't save anybody here. In fact, it's just the opposite. Jason says it best in the first clause of his rule, "Forget the rest of the world," before he fucks up and seals his fate with, "and hold on to the ones you love the most." Of course he'll die first! (Maybe that's why killing all those yuppies works: Tom Cruise slummed it as a blue collar, deadbeat dad to survive Spielberg's War of the Worlds. Privilege breeds contempt? Perhaps. I mean, I sure did hate that Tom's wife's parents (and all of Boston, for the most part) were relatively unscathed.) Still: It's not worth hating, and it's worth looking at, even if it's a little (a lot?) stupid.

The coolest thing about Cloverfield is probably that, despite itself, I sat not apoplectic and bewildered but jazzed up and ready since I was so caught up with the idea that a monster movie was made like this. Okay, The Blair Witch Project did it first, I guess, and I like that it was a hit, but this one is a real big time movie, with one of those genius hype-generating marketing campaigns. (Okay, its marketing was kind of a rip off of the Blair Witch internet craze, too.) But, anyways, Cloverfield made a ton of money this weekend and it's a weird, not-typical Hollywood movie. Even The Bourne Ultimatum isn't this wobbly. I don't really know anything about avant-garde cinema but that late auto-focus fidgeting in the grass may be one of the coolest/weirdest things in a blockbuster I've seen in a while. Starting here of all places I can start to see why Cloverfield is different than Blair Witch: the camera is just another witness here, instead of some kind of agency device. It's also the reason it's a pretty muddled movie. For all the silly humanism in the stupid love story, the filmmaking itself isn't really interested in humans. It's a document --some weird artifact the government found? -- of human kind's idiot notion that they should win any and every battle because they can love. But love doesn't save anybody here. In fact, it's just the opposite. Jason says it best in the first clause of his rule, "Forget the rest of the world," before he fucks up and seals his fate with, "and hold on to the ones you love the most." Of course he'll die first! (Maybe that's why killing all those yuppies works: Tom Cruise slummed it as a blue collar, deadbeat dad to survive Spielberg's War of the Worlds. Privilege breeds contempt? Perhaps. I mean, I sure did hate that Tom's wife's parents (and all of Boston, for the most part) were relatively unscathed.) Still: It's not worth hating, and it's worth looking at, even if it's a little (a lot?) stupid.Like I said above, it's not the screenplay that got me hot (if it did, indeed, get me bothered): it was how Abrams and director Matt Reeves used the digicam to capture the mayhem. It should be no surprise that the best sequence of the movie is the one you get a glimpse of in the trailer: the one where the Army rolls through shooting the monster with all its might, including some rockets. It's a much better commentary on our relationship to Iraq (as experienced by redacted television news) than that annoying scene in 28 Weeks Later on the tram after the kids fly into London -- and it's much better than the 9/11 ash quote from earlier in the movie. But what happens next? The yuppies go inside, underground even, and cry about their woeful lot. At least uber-cutie Marlena (I want Lizzy Caplan's hairdo) doesn't shed any tears -- she's just kinda pissed. I wanted more of that (and less whining) to go along with my apocalypse.

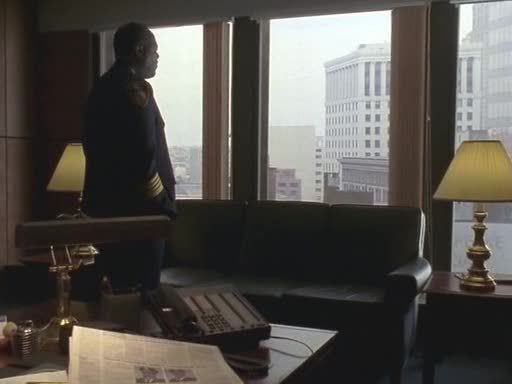

The Monday Evening Wire. Just a Step Behind.

Episode 53, "Not For Attribution"

I'm not sure if I mind or not, but I don't have the privilege of On Demand, nor did I receive the first seven episodes of this season in advance of their air dates: I watch each Wire episode every Sunday night when it airs here in Berkeley, sometimes after having already read a few reviews of it. By the time I finish my weekly recap, it's usually mid-morning on Monday and I've even read comments about those reviews. So, with that said, and knowing that other people have said what I'm about to say, I'll still say: funniest episode around! The kind of giggles popping throughout my living room of friends were reminiscent of the early part of the final Sopranos season. The first two episodes (I hear from every season) afford the remaining episodes a certain element of time. Time for us to see McNulty as a complex, and therefore more complete character, although he still acts like a drunk slut, dicking around with a badge and a bit of ambition, saying things like, "We have to kill again!" Two Omar-less episodes, and a third one with 55 Omar-less minutes provided the necessary tension to turn genuine anticipation of where he is living and what he is doing into real fear once the tears drip down his cheek and the final credits fade in. The re-contextualizing of Marlo into the business world after, as I said last week, being cool under the crown for the opening two episodes made for a meaningful re-examination of what he and his crew are all about. In the previous two weeks everything was fast -- quick emotions coming from abstracted characters in ambiguous parts of B-more -- quick cuts and fast talk. Slowing this episode's pace gave us viewers the time for this week's happenings, and the events of the last three as a whole unit of storytelling, to seep in. Maybe this is why "Not For Attribution" was so affective.

Burrell cooked the books and essentially fired himself. Clay Davis is probably going to jail. Scott Templeton conjured up another piece of bullshit, this time a quote from Narese, a source too close to his office for him not to get caught. Crimes in high places, dishonesty on all fronts in upper class Baltimore, again David Simon proves this city is shitting all over itself. Unlike the previous weeks (and the previous season), though, bad news was followed by hope. Daniels, the best cop the show has produced, very well may take over as commissioner. Alma Gutierrez, with Templeton's (hopefully) inevitable fall, will emerge as the new face of the now depleted Sun journalist staff. And, as far as my personal satisfaction goes, I got to hear someone yell "Focus, mothafucka, focus!" at Clay Davis. The plot foundation provided in the last two weeks (no matter how seemingly unsteady) gave this week the ability to be two things, to go two ways: good and bad, happy and sad, unbearably serious and laugh-out-loud funny.

Burrell cooked the books and essentially fired himself. Clay Davis is probably going to jail. Scott Templeton conjured up another piece of bullshit, this time a quote from Narese, a source too close to his office for him not to get caught. Crimes in high places, dishonesty on all fronts in upper class Baltimore, again David Simon proves this city is shitting all over itself. Unlike the previous weeks (and the previous season), though, bad news was followed by hope. Daniels, the best cop the show has produced, very well may take over as commissioner. Alma Gutierrez, with Templeton's (hopefully) inevitable fall, will emerge as the new face of the now depleted Sun journalist staff. And, as far as my personal satisfaction goes, I got to hear someone yell "Focus, mothafucka, focus!" at Clay Davis. The plot foundation provided in the last two weeks (no matter how seemingly unsteady) gave this week the ability to be two things, to go two ways: good and bad, happy and sad, unbearably serious and laugh-out-loud funny.  I have to say, McNulty (or rather Dominick West) was so good this week. Drunk throughout, he managed to materialize a case (with red ribbon), persuade the morgue, leak the story to Alma, and forge his dead friend Ray Cole's signature. Unfortunately, for him, he was drunk, and sloppy, and his homeless serial killer case went nowhere. That is until Freamon said he should give the killer a name and some twisted trademark to give the case new life -- and, probably, limit the amount of time Bunk can stay out of it (after all Bunk and Jimmy are two peas in a sick and withered pod; how can one go without the other?). Of course, Jimmy and Freamon are doing all this in the hope of re-opening the Stanfield detail under the impression they are just "weeks away" from sealing the case. But, as Chris said to Snoop, after arguably the most ruthless scene to date, "We got to switch it up." The tail McNulty and Freamon have on Marlo may be interrupted. Mr. Stanfield entered some new terrain this week himself -- not just in the Caribbean, but also with the Russians. Branching out like this, his posture took on something like a tough, but ignorant, boy. Dirty bills wrapped and placed in a sharp suitcase don't make them clean, as he learns from Vondas. And, as Marlo's dependence on Prop Joe increases, his attempt at cutting him out becomes less realistic. Vondas makes this clear to Marlo: "Everything is clean with Joe." Something tells me (and my expert detective skills), that Omar's presence might just disrupt things for Marlo a tiny bit as well.

I have to say, McNulty (or rather Dominick West) was so good this week. Drunk throughout, he managed to materialize a case (with red ribbon), persuade the morgue, leak the story to Alma, and forge his dead friend Ray Cole's signature. Unfortunately, for him, he was drunk, and sloppy, and his homeless serial killer case went nowhere. That is until Freamon said he should give the killer a name and some twisted trademark to give the case new life -- and, probably, limit the amount of time Bunk can stay out of it (after all Bunk and Jimmy are two peas in a sick and withered pod; how can one go without the other?). Of course, Jimmy and Freamon are doing all this in the hope of re-opening the Stanfield detail under the impression they are just "weeks away" from sealing the case. But, as Chris said to Snoop, after arguably the most ruthless scene to date, "We got to switch it up." The tail McNulty and Freamon have on Marlo may be interrupted. Mr. Stanfield entered some new terrain this week himself -- not just in the Caribbean, but also with the Russians. Branching out like this, his posture took on something like a tough, but ignorant, boy. Dirty bills wrapped and placed in a sharp suitcase don't make them clean, as he learns from Vondas. And, as Marlo's dependence on Prop Joe increases, his attempt at cutting him out becomes less realistic. Vondas makes this clear to Marlo: "Everything is clean with Joe." Something tells me (and my expert detective skills), that Omar's presence might just disrupt things for Marlo a tiny bit as well.  As Marlo conducted his business this week, so, too, did his muscle. The torture and eventual killing of Butchie was terrifying. Not just Chris's demonic stare into the side of the blind man's head he was about to blow out, but also Snoop's slight cock of her own head, and inquisitive look into Butchie eyes after the shooting, did what last week's killings did not: both gestures took the time to show us what these two psychos are really up to. The willingness to kill, and now to live on the run -- for Marlo and only for Marlo -- separate these two from Michael, who kills for Bug's (and Dukie's) future. The pain of seeing Michael, alone, in the dark with his head down was gone as quick as Dukie said, "We should do somethin Mike," and he turned a smile. This was followed by the cute family of three boys running and laughing with lollypops at Six Flags. Their interaction with two Sidekick-holding girls from Virginia only enriched an already priceless sequence. "You guys live on your own?" asks the young white girl. Dukie: "Yea, and Bug." "That's tight!" Of course, though, when the three return to Baltimore it's night, Michael's corner is dark, and he's instantly interrogated by Monk. Michael is always hard so the harangue doesn't really phase him until he learns Chris knows, too, that he was gone all day without a word. Knowing that, he puts his head back down and walks off alone. There's no fun to be had on the corner, whether you're a kid or not. "Nice dolphin, nigga," and Dukie's head drops too.

As Marlo conducted his business this week, so, too, did his muscle. The torture and eventual killing of Butchie was terrifying. Not just Chris's demonic stare into the side of the blind man's head he was about to blow out, but also Snoop's slight cock of her own head, and inquisitive look into Butchie eyes after the shooting, did what last week's killings did not: both gestures took the time to show us what these two psychos are really up to. The willingness to kill, and now to live on the run -- for Marlo and only for Marlo -- separate these two from Michael, who kills for Bug's (and Dukie's) future. The pain of seeing Michael, alone, in the dark with his head down was gone as quick as Dukie said, "We should do somethin Mike," and he turned a smile. This was followed by the cute family of three boys running and laughing with lollypops at Six Flags. Their interaction with two Sidekick-holding girls from Virginia only enriched an already priceless sequence. "You guys live on your own?" asks the young white girl. Dukie: "Yea, and Bug." "That's tight!" Of course, though, when the three return to Baltimore it's night, Michael's corner is dark, and he's instantly interrogated by Monk. Michael is always hard so the harangue doesn't really phase him until he learns Chris knows, too, that he was gone all day without a word. Knowing that, he puts his head back down and walks off alone. There's no fun to be had on the corner, whether you're a kid or not. "Nice dolphin, nigga," and Dukie's head drops too.

Although this week proved to be a multi-layered and complex episode, the Sun's parts were strikingly clear. If it wasn't enough that they are downsizing in all the wrong areas, for all the wrong reasons, we were also given two scenes of two predominant characters (Jimmy and Rawls) actually throwing away papers in a fit of frustration. David Simon doesn't like the Baltimore Sun, and this bit of didactic TV doesn't rub me the wrong way at all. Newspapers generally suck! If there's anything more to be taken from the Sun, it's that they are going to have to do "more with less" (as we had pounded into our heads). Hopefully "less" will mean "more" with Alma and Gus, as they are single-handedly keeping the Sun interesting and integrated with the rest of the show. I'm pleased that I didn't get so down on the first two episodes, no matter how "bad" they were, as they were clearly necessary progressions to what was possibly the best Wire I've seen. The affective intensity on both (on all!) sides of the dramatic spectrum proved that this show it at its best when it takes it time.

"They're dead where it doesn't count." -- Fletcher

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Welcome Notes.

RWK: This is a post to welcome some estrogen into our midst here at VINYL IS HEAVY as I have extended invitations to not one, not two, but three fine young ladies to contribute posts on a regular basis (whatever that means). During the first week of the month of the year I mentioned, rather tangentially, that the first new member of our crew, Claire Twisselman, who I will let explain herself below, had been added to the masthead. Today I welcome publicly Sanaz Yamin, bookmaker extraordinaire, and Bryn Esplin, a dear and fellow Pavement lover. I met Bryn about a year ago in a section for a class lectured by this guy. Sanaz was in the course, too, but not our section. However, it was not until this past fall semester, in another class taught by that guy, that we three became buddies on the real. They are two of the funniest people I know. Plus, they've got taste and style. Here's hoping they blow up the sphere this year, too. Stay tuned for all kinds of cool from all three as we venture forth in 2008.

RWK: This is a post to welcome some estrogen into our midst here at VINYL IS HEAVY as I have extended invitations to not one, not two, but three fine young ladies to contribute posts on a regular basis (whatever that means). During the first week of the month of the year I mentioned, rather tangentially, that the first new member of our crew, Claire Twisselman, who I will let explain herself below, had been added to the masthead. Today I welcome publicly Sanaz Yamin, bookmaker extraordinaire, and Bryn Esplin, a dear and fellow Pavement lover. I met Bryn about a year ago in a section for a class lectured by this guy. Sanaz was in the course, too, but not our section. However, it was not until this past fall semester, in another class taught by that guy, that we three became buddies on the real. They are two of the funniest people I know. Plus, they've got taste and style. Here's hoping they blow up the sphere this year, too. Stay tuned for all kinds of cool from all three as we venture forth in 2008. Claire's got a nerd alert: I'd read VINYL IS HEAVY since the summer when I met Ryland by chance in Los Angeles, one day into 2008. I'm flattered he decided to allow me to write for his blog because I'm not a film major -- and I'm not a rhetoric major -- but an English major. I'm an English major who likes movies more than books, when I'm honest with myself. (I also like fish tacos more than grilled cheese sandwiches but I eat more grilled cheese, so go figure.) Anyways, I'll try not to genuflect too much but I gotta say that I'm pretty pleased to explore the blogosphere in public now after a year of lurking. I don't know that much about movies. And I've never read any Stanley Cavell except what Ryland's quoted here. But I'm game. So thanks, Ryland, for welcoming me! I hope I can live up to the call!

Claire's got a nerd alert: I'd read VINYL IS HEAVY since the summer when I met Ryland by chance in Los Angeles, one day into 2008. I'm flattered he decided to allow me to write for his blog because I'm not a film major -- and I'm not a rhetoric major -- but an English major. I'm an English major who likes movies more than books, when I'm honest with myself. (I also like fish tacos more than grilled cheese sandwiches but I eat more grilled cheese, so go figure.) Anyways, I'll try not to genuflect too much but I gotta say that I'm pretty pleased to explore the blogosphere in public now after a year of lurking. I don't know that much about movies. And I've never read any Stanley Cavell except what Ryland's quoted here. But I'm game. So thanks, Ryland, for welcoming me! I hope I can live up to the call! be- Vinyl is heavy, and so am I.

be- Vinyl is heavy, and so am I.Long-time listener, first-time caller here, and I couldn’t be more excited about contributing to ViH.

I’m terrible with introductions. Barring such a phobia, I would have introduced myself to my gracious host, Ryland, long ago; instead, I sat silently during hours of lecture, making metaphors, moons and eyes at him from afar. A fellow UC Berkeley Rhetoric major, I’m an ardent admirer of generous criticism, believing it neither oxymoronic nor indulgent. I hope to contribute to all avenues of ViH: film, music, images, discourse, and fish tacos, believing them inextricable and delicious. Besides unmanned explorations into the things themselves, I hope to also examine the contexts and the ways in which we enjoy or maybe even despise them.

My introduction, tardy, reluctant, inevitable, has gotten my voice this far: a soft, silent swagger, much more my style.

Sanaz says: First and foremost, thank you, Mr. Ryland, for welcoming me. And thank you, Bryn, for sending me your intro before I wrote mine. As well as agreeing that generous criticism is not oxymoronic, I would also like to add that neither are expert amateurs nor blind viewers. As a recently freed member of the latter and a hopeful prisoner of the former, I've come to view VINYL IS HEAVY as a venue for criticism, conversation, elucidation and interpretation. I couldn't be happier than strolling down this street with this company. Perhaps we could call ourselves "the Ambulators."

Sanaz says: First and foremost, thank you, Mr. Ryland, for welcoming me. And thank you, Bryn, for sending me your intro before I wrote mine. As well as agreeing that generous criticism is not oxymoronic, I would also like to add that neither are expert amateurs nor blind viewers. As a recently freed member of the latter and a hopeful prisoner of the former, I've come to view VINYL IS HEAVY as a venue for criticism, conversation, elucidation and interpretation. I couldn't be happier than strolling down this street with this company. Perhaps we could call ourselves "the Ambulators."

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

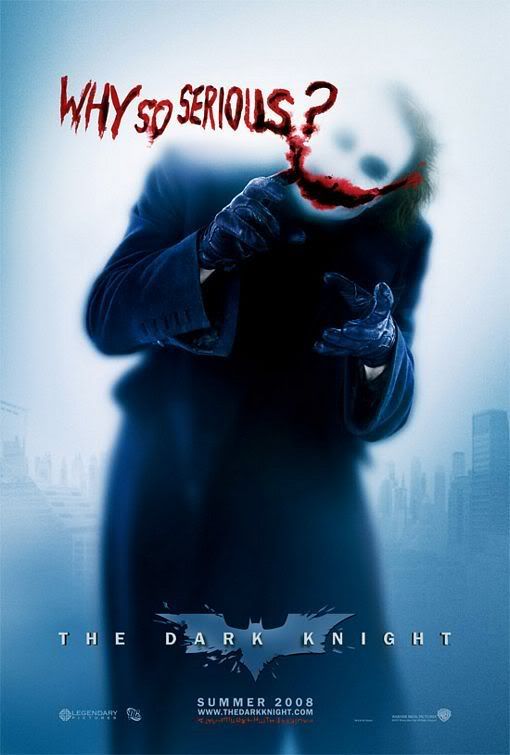

Joker for the day.

As I questioned over at Free Nikes, is this my most anticipated film of 2008? Right now I think it is. How can you resist that tagline? Or that third poster? --RWK

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

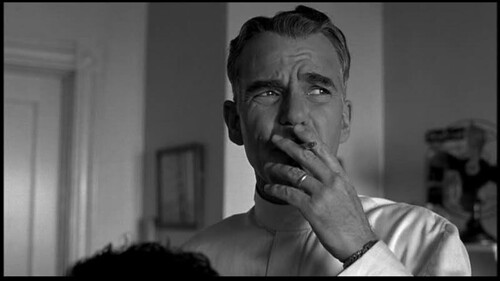

COEN COUNTRY: From the Second Chair to the Electric Chair. The Barber's American Odyssey. The Man Who Wasn't There.

"What kind of man are you?"

Many a review regarding their most recent film, the effectively affecting No Country For Old Men, has emphasized the flawlessness with which the Coen Brothers have translated Cormac McCarthy's novel from the page to the screen. Whole sections of dialogue have been lifted verbatim from the acclaimed book. The pacing and chain of events in the film are nearly identical to those in the book. Yet the whole film manages to filter its way through the Coen's eerily singular vision, ending up not just a meticulously respectful recreation, but also a well-worn, completely familiar experience. If No Country is one of the greatest book-to-film adaptations of all time then I argue that 02001's The Man Who Wasn't There (if not my absolute favorite of their films, definitely a member of the mile-high club with Barton Fink and The Big Lebowski) is the inverse. Namely, in the completely original screenplay of a reticent, retiring barber and the severe choices he makes, the Coens have not just written the Great American Pulp Novel; they've cast, produced, and directed it too.

The Man Who Wasn't There feels much more at home as a last minute addition to Ethan Coen's enjoyable pulp pastiche, the short story collection Gates of Eden

The Man Who Wasn't There feels much more at home as a last minute addition to Ethan Coen's enjoyable pulp pastiche, the short story collection Gates of Eden

"Me, I don't talk much... I just cut the hair."

Ed Crane is less an Everyman than a Nowhere Man. A cypher, his character owes more to Camus than, say, Cain or Chandler. Yet like the work of the latter, his entire existence, or lack thereof, is laid out before us in the very first scene. As readers, we know of Philip Marlowe's ideals, persona and conviction from the opening pages of every novel he stars in and time and again, these qualities steadfastly refuse to change. The same goes for Ed Crane, although compared to Marlowe, who springs forth fully-formed, Crane has already been and will always remain a specter. We know implicitly in the film's first few minutes that he was born into this. No event altered his outlook or carriage. He has spent his entire life silently watching from the shadows. Observing, rarely judging. He sits quietly by as his brother-in-law tells one long-winded yarn after another. He has known for years of his wife's infidelity though it never really bothers him. Later, he uses this knowledge for nefarious purposes but it is really only a means to an end. He is -- in a word -- unflappable.

After a life of pure, simple existence, Crane finally decides to take a chance when he meets an entrepreneur looking for backers for a new invention called Dry Cleaning. We never really find out what about the proposal catches Crane's eye and sends his story down the fatalistic Noir path. Is it the money? If so, what does he want it for? This is a man of little ambition. Does he want to get back at his wife's partner in infidelity, her boss at the local department store, whom he eventually extorts? Is he just bored? Regardless, like No Country For Old Men, the money means nothing. It is utterly trivial. What does matter is that this man, this barber, has finally set something in motion that, for better or worse, changes his life and the lives of those around him forever.

After a life of pure, simple existence, Crane finally decides to take a chance when he meets an entrepreneur looking for backers for a new invention called Dry Cleaning. We never really find out what about the proposal catches Crane's eye and sends his story down the fatalistic Noir path. Is it the money? If so, what does he want it for? This is a man of little ambition. Does he want to get back at his wife's partner in infidelity, her boss at the local department store, whom he eventually extorts? Is he just bored? Regardless, like No Country For Old Men, the money means nothing. It is utterly trivial. What does matter is that this man, this barber, has finally set something in motion that, for better or worse, changes his life and the lives of those around him forever. I find Ed Crane's burgeoning passion, regardless of implicit reasons to be the movie's main motive. Though he remains outwardly unreachable through the duration of the film, beneath the surface he becomes excited with possibility. His interest in the dry cleaning scheme and later his not-quite platonic adoption of a teenage pianist are the first pangs of genuine enthusiasm this man has ever known. Of course in true Noir (and Coen) fashion everything quickly goes awry, often in devious ways we never saw coming. Crane ends up killing his wife's lover, who in turn killed the dry cleaning entrepreneur and accidentally impregnated Ed's wife, who herself is jailed for the first murder, who subsequently commits suicide. Eventually, after trying to make things somewhat right, but instead only further ruining the lives of those around him, Crane, too, is jailed for a murder. It just so happens to be the wrong killing but no matter. One could argue that, because of his actions, he's responsible for this one, too.

I find Ed Crane's burgeoning passion, regardless of implicit reasons to be the movie's main motive. Though he remains outwardly unreachable through the duration of the film, beneath the surface he becomes excited with possibility. His interest in the dry cleaning scheme and later his not-quite platonic adoption of a teenage pianist are the first pangs of genuine enthusiasm this man has ever known. Of course in true Noir (and Coen) fashion everything quickly goes awry, often in devious ways we never saw coming. Crane ends up killing his wife's lover, who in turn killed the dry cleaning entrepreneur and accidentally impregnated Ed's wife, who herself is jailed for the first murder, who subsequently commits suicide. Eventually, after trying to make things somewhat right, but instead only further ruining the lives of those around him, Crane, too, is jailed for a murder. It just so happens to be the wrong killing but no matter. One could argue that, because of his actions, he's responsible for this one, too.

"The more you look, the less you really know."

In the final scene, The Barber delivers the last paragraph of his manuscript while observing the haircuts of the men who have sentenced him to die. He does this from the electric chair as casually as he did in a waiting room earlier in the film. This final moment shares with it the calm literary coda that punctuates No Country's muted finale. In the latter, Tommy Lee Jones' retired, world-weary Sheriff tells his wife of his dreams. They involve his father and how he is ready to meet him, how he has accepted death. The Barber, too, is ready and willing to go, but his final words delve a little deeper as we watch this man, who was there all along in flesh, finally leave us. He talks of meeting his wife in the afterlife. Despite all of the harrowing, horrible things that have happened to the two of them, and besides the fact that they never really knew one another, he can't wait to meet her. He speaks of the words that don't exist here and how he'll find them when he gets there.

And then the switch is pulled and we too are gone, obliterated by pure white light. The final chapter break in our messy little story that just hasn't been published yet.

Posted by

Mikey

at

11:45 AM

3

grooves

![]()

Labels: America, appreciation, Coen Brothers, MS, noir, novels