A throwaway attempt at more generosity. A speak-and-spell second visit with Jesse James.

by Ryland Walker Knight

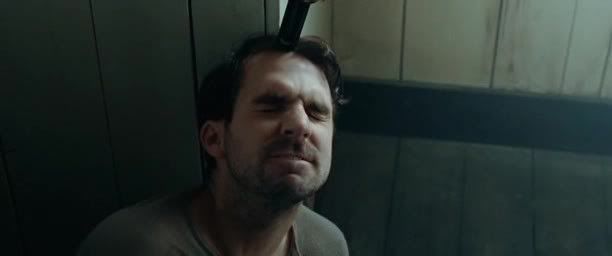

Sometimes I amaze myself. Why in the world did I watch this picture a second time? As much as I've come to appreciate the opportunity to be persuaded by a strong argument (that is, to change my mind), nothing, or close to, can save The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford from my distaste. I'll grant it Casey Affleck: I was wrong about him: his performance as Robert Ford is pretty perfect. In fact, all the acting is good, especially Paul Schneider, as I said way back when. But I still won't grant it the voice-over or the vaseline. Here's a caveat: I didn't even finish it this time. I got to Zooey Deschanel after skipping Nick Cave and quit. So why write this? Well, sometimes the picture's okay, maybe even good, but I think it's mostly due to Roger Deakins' work as cinematographer. That, yes, and before we saw Hoberman speak on Sunday I re-read his review of Dominik's picture, which is very generous and shames my earlier attempts to say something -- anything -- about this picture. So, I turn it over to him for a spell:

Jesse James was shot largely in midwestern Canada, but there's something suggestively Australian about the way the movie dramatizes empty space and loneliness. Full of slow dollies and haunted close-ups, this is a film of Rembrandt lighting and Tarkovsky weather. The sun pours down like honey and Vaseline limns the lens. The skies shimmer with onrushing clouds; the fields dance with waving brown weeds, for which Nick Cave and Warren Ellis have provided a suitably spacey score.

Although not as radically defamiliarizing as Jim Jarmusch's avant-western Dead Man, Jesse James has the feel of an attic ransacked for abandoned knickknacks. There are intimations of what Greil Marcus called the "old weird America"—a sneaking sense that Dominik might have preferred to shoot the whole thing through a pinhole camera or fashion his story out of musty daguerreotypes. But then, as demanding as the movie is, maybe it's just old-fashioned crazy. [Full review]

That last line may betray a certain evaluation or judgment but the thing that makes this such a great piece is how non-judgmental it reads. He found the picture to be interesting in ways I failed to when I wrote this:

Voice-over is a routinely botched device, but this kind of literalization is unbelievably painful. The film opens describing Pitt’s Jesse James as a mysterious and powerful figure who can affect any situation despite not affecting any situation he’s shown acting within. This might be played as ironic in another film, but Dominik’s vision is only ever clouded by an earnest self-importance, which renders irony an impossibility. Were the cinematic blunders not so mind-boggling and blunt, the film’s shortcomings might have played light and parodic. Unfortunately, the film’s sobriety is suffocating, not enlightening. When the voice-over tells you James was concerned about being caught, you see Pitt mugging, searching the skyline for an answer, and you can tell he’s concerned about being caught. But just in case you couldn’t connect the dots, he has some dialogue to that effect as well. [Full review]

I don't even think I remembered the film correctly. I don't think that scene exists. I was probably thinking of all those other sequences where Dominik's pictures tell you all you need to know but get overdubbed with narration, like the day before the "assassination" when Bob wanders through the James household trying on Jesse's life: Bob touches Jesse's jackets, drinks Jesse's water, smells Jesse's sheets, bends a finger to mimic Jesse's mangled left hand. All the while the narrator describes the same things -- for what reason, I'm not quite sure. The images are already rich and evocative enough. The attentive viewer can piece it together. Try to imagine any scene in No Country or There Will Be Blood with a narrator. Hear him (always him) saying, "Then Chigur readied his air compressor, and shot the lock through the door into the trailer, where it bounced off the wall opposite"; or, "Plainview watched Eli bidding fairwell his so-called flock at the depot and remembered the pain of Eli's slaps not only to his impassive face but to his wrinkled and confused soul; then he averted eye contact as Eli ascended the locomotive." Right. As I said before, last year (like Larry Aydlette, too, I think), Manohla Dargis probably wrote the best review of the picture because she clearly liked some aspects of it but found ways to evaluate what went wrong without too harsh a sting. And because she uses the film as its own evidence, which I seem to have failed to do with any grace.

It’s a curious performance, at once central and indistinct, but then, so too is the character. Based on the novel of the same title by Ron Hansen, the film introduces James at the beginning of his end. Hunkered down in some woods, surrounded by darkly dressed men and leafless birch trees, and framed by Roger Deakins’s impeccable, stark, high-contrast cinematography, he looks a vision. This isn’t just Jesse James — it’s also Jim Morrison at the Whisky in 1966 with a dash of Laurence Olivier, a touch of Warren Beatty and more than a hint of Ralph Lauren. It’s the beautiful bad man, knowing and doomed, awaiting his fate like some Greco-Hollywood hero, rather than the psychotic racist of historical record.

The movies have their truths, which rarely align with those of history. Taken on its own narrow, heavily aestheticized and poetic-realist terms, then, “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” works. The cinematography may speak to Mr. Dominik’s yearning for meaning and importance more than it does of his outlaw, but the visuals often dazzle and enthrall. (The images that approximate the blurred distortions characteristic of pinhole photography are especially striking.) They also distract and, after a while, help weigh down the film, which sinks under the heaviness of images so painstakingly art directed, so fetishistically lighted and adorned, that there isn’t a drop of life left in them. Instead of daguerreotype, Mr. Dominik works in stone. [Full review]

What's striking is how similar, underneath, her read is to Hoberman's and what's intriguing is how different people manifest their similar perspectives differently. It's why it's fun to read film criticism, or film reviews, even months later, even when the film does not completely satisfy. Sometimes, though, you wind up seeing a completely different picture than others, which is where Walter Chaw's review comes into play. Maybe more to the point, the problem I find with this review, which is sparklingly written, of course, is that it gives me more a sense of the associations the film produced for Chaw than a sense of the film itself, which is something Hoberman does so well while skirting this kind of piece. Still, in a way, I wish I had been fortunate to see this picture: it sounds awesome.

Kiwi director Andrew Dominick's heroically pretentious The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (hereafter Jesse James) is a deflated anti-western in the tradition of Peter Fonda's The Hired Hand and Terrence Malick's Badlands. Broadly, it's a magnification of the Nixonian malaise that infected the early-seventies, its suggestion that things aren't much worse now than they were then complicated by three decades of cynicism. As a piece, it's almost completely sapped of energy, though it isn't deadpan like Jarmusch's Dead Man. No, think of it as more of a dirge: not ironic, but post-modern; not a death march, but mournful. It's how J. Hoberman once (derisively) described Body Heat, a "remake without an original"--Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid corrupted by McCabe and Mrs. Miller, the whole of it shot through with an autumnal soft focus that looks exactly like the reunion sequence that pushes the third act of Bonnie and Clyde. It vaguely resembles an insect caught in an amber sepulchre. Yet despite its obvious pedigree, it is all of itself, infused with the spirit of the now, suffused with author Ron Hansen's transcendental prettiness (the film is based on his novel), and, as framed by DP Roger Deakins' painterly eye, overwhelmingly beautiful. Deakins is given the keys to the kingdom here and every moment of Jesse James looks like mythology pulled through a cinematic loom, often leaving the edges of the frame lanolin-indistinct as they trail off into history. I hadn't thought it possible to see our current crises of faith cast as romantic, but there it is. [Full review]