Saturday, February 28, 2009

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Your forking: Birdsong and Waiting for Sancho

by Ryland Walker Knight

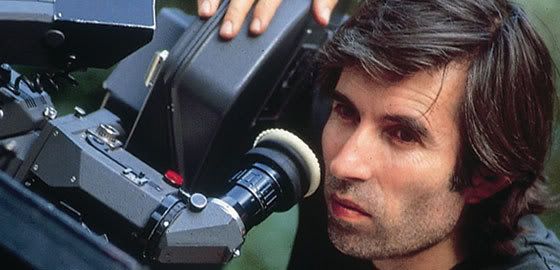

Tonight begins the week-long NYC premiere run of Albert Serra's Birdsong at Anthology Film Archives. I wrote a few words about the film and its accompanying "making of" picture for The Auteurs' Notebook, which you can read by clicking right here. As can be seen above, Serra's imagining of the three "wise men" and their journey to see the newborn Christ is gorgeous, stately, mysterious and (surprising, baffling to me) its clever-clumsy-absurd jokes about bodies and idiocy are close to hilarious. But it's not a rollicking road picture. It's more like you're watching a myth moulded into reality through quotidian (boring?) tasks like, say, walking. These three spend a lot of time simply walking, or trying to walk.

Their path is blocked by elements and by bodily stupidity. They get lost, it seems, constantly. Every diversion-tack surprises, and takes forever. The most delicious moments happen without sound.

Mark Peranson's accompanying Waiting for Sancho does not explain everything, nor provide a perfect picture of the people involved with Serra and his exploratory cinema, but it does give us more jokes, and a little context. It does show us his wardrobing skills. It's also longer than Birdsong, oddly enough, and somehow even less happens in its five days of activity than the 98 minutes of black and white trudgery. The best jokes in Peranson's films are the ones about the folly of improv cinema, about its arduous accretion flipped into a dance or a bottle of wine, about "hip" t-shirts on rather "un-hip" but loveable! gordos, about how we deal with muck. Seen together with Birdsong we get a better idea of the sense of fun behind Serra's picture, even if his work never seems quite as goofy as it truly is, or could be.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:00 AM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: Albert Serra, Anthology Film Archives, comedy, linkage, myth, The Auteurs

Thursday, February 19, 2009

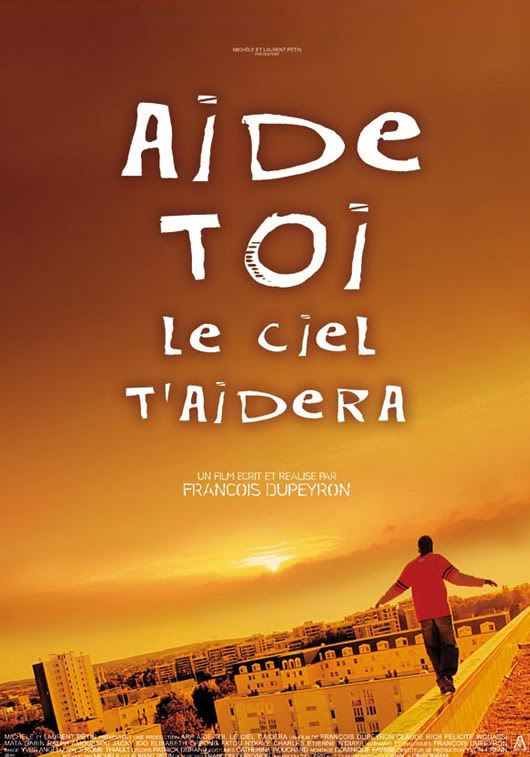

Hot in here: Aide-toi le ciel t'aidera

Telluride #6, Rendez-vous #2

by Ryland Walker Knight

by Ryland Walker Knight

Félicité Wouassi stars as Sonia, mother of three and wife to a deadbeat, in François Dupeyron's Aide-toi le ciel t'aidera. She broils through the picture, fierce and sexy, lending it her always-brimming face and her forever-fighting grace. Routinely shot from a canted angle below, Dupeyron builds a portrait of Sonia as larger than her station—although, of course, she is never quite free from her life's limits. There will always remain an obstacle. What keeps Sonia afloat, we see, is her understanding that, equally, there is always a solution. Sonia's solutions, though, often startle. They hardly look like the right choices, but she owns these choices and she does make things happen, and settle, with an eye to consequence.

Set during the 2003 heat wave, the image washes yellow and red through most of the film, a picture of heat as has yet been captured (as far as I have seen) on a digital format. The beads of sweat on skin glisten and the pools under arms (or across backs) on shirts stick, feel like a too-hot summer. It's not Spike Lee and Ernest Dickerson's celluloid smear, it's some kind of glitchy pop of light punctuating a field of humidity. The weight of the boundless and roving camera rests in the image's diffusion, somehow, where color is like paint, a layer unto itself. This is nothing new, of course, as plenty have proven, like Godard (from Contempt to Eloge), and it's not quite Costa, but this desire to give face to the weight of poverty is another refreshing element reflected in the film's built-on-proximity mise-en-scène. If pressed, I'd say there's more Cassavetes than anything in the background here with all the focus on the face and all the insistence on the event. There's a lot of thisness.

A funny (albeit grave) little film that may, with a little help from this Rendez-vous series exposure, gain a following and blossom into some kind of "art-house hit" or what have you, I saw Aide-toi initially at the Telluride Film Festival last summer. I'm happy it went on to win Wouassi an award at Toronto, and that it appears now, in New York at least, for more to see. When we saw it included in this program, my friend Martha and I asked ourselves, "How come we never wrote about it back then? Or, at least, made more than a passing mention of it to more people than our non-internet friends?" Part of it was due to the rush of that weekend. Another part is that Aide-toi, although it hits all its targets, is not as immediately arresting and demanding (to say complicated and conflicted) a film as, say, Waltz With Bashir. In fact, Dupeyron's film may be too good (too fun?) for its own good. It will likely draw a lot of "sure, I get it's great; so what?" reviews, and could very well attract a certain middlebrow audience, but for some reason I think it will fade into that fog of unjust American neglect.

—All while the assuredly more pointed (although plenty lovely) L'Heure d'été by Olivier Assayas will be distributed by IFC Films in May and, thanks to its (ahem, more white) cast and its typically digestible ideas about art's worth, it will be an easy thing to laud.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:30 AM

3

grooves

![]()

Labels: close-ups, faces, Félicité Wouassi, France, François Dupeyron, Rendez-Vous With French Cinema 2009, rwk, Telluride 2008

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Run into a swim, sleep by a beach.

Rendez-vous #1

by Ryland Walker Knight

I will say more soon (for a different outlet), but I wanted to say right now that, yes yes yes, I am predictable: this new Claire Denis film, 35 rhums, is lovely. Walking around in the rain this afternoon I continually thought, "Perfect; one hundred percent." This endorsement is assured hyperbole but, please, let me tell you: there is nothing else around as easy to love for all the right reasons as this film. It plays four times in mid-March as part of this year's Rendez-vous with French Cinema series programmed by the fine folks at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. The film opened in France today, as the no-subs trailer attests below, but because I cannot give an additional link to some kind of release schedule here in the States, I should like to encourage all those who can to see this thing while they can, to hop uptown and soak up that big and bright screen that the Walter Reade offers.

Also, this gives me a no-embedding-allowed opportunity to link to The Commodores' only Grammy-sanctioned hit, "Nightshift" (some already know this is a personal favorite of mine), as, once again, Mme Denis' taste is impeccable and her timing better than perfect and the use of this song in the film is well past sublime.

UPDATE: More from Martha at What Is This Light. Read it!

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

7:30 PM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: beauty, blogging, Claire Denis, family, linkage, Rendez-Vous With French Cinema 2009, rwk, The Commodores

Links at the end of the world.

by Ryland Walker Knight

Just a quick notice that, yes, I will be taking over half of the Links for the Day duties (alongside the stalwart Todd VanDerWerff) at The House Next Door starting with a set for tomorrow, Thursday, February 19th, 2009. It should be fun. It's another thing to add to my full plate but, for some reason, I like the idea of silly projects. If you ever have any ideas or wishes or enthusiasms or, well, links... send them my way!

UPDATE: The first day.

Friday, February 13, 2009

LOW BUDGET EYE CANDY #1: THX-1138

by Steven Boone

[New note (8/6/09): A new and improved, to say operational, version is now ready and available for your viewing pleasure above as part of our VINYL-wide switch to Vimeo. —rwk]

[New note (2/14/09): A new and improved, to say tighter and cleaner, version is now ready and available. If pressed, or not, Steve might say I jumped the gun on posting the original iteration of this video. What can I say? I was excited; I was impressed. In fact, I still am. This little thing is cool and I'm happy to host it here. —rwk]

[Original note (2/2/09): Steve's credit at the close is for BIG MEDIA VANDALISM. However, as the Odienator has taken over that space for Black History Mumf, we decided to post this video here for the time being. Hope you digg it as much as we do. —rwk]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

11:00 PM

14

grooves

![]()

Labels: beauty, George Lucas, images, looking, mise-en-scene, pedagogy, SB, sound design, video essay

Breadlines & Champagne! UPDATED. TWICE.

by Ryland Walker Knight

To counter our chill with a laugh (and a hug?), Film Forum has programmed the Breadlines and Champagne series, a month-long celebration of Great Depression cinema. The fun begins this weekend with an opening night screening of Wesley Ruggles' 1933 film, I'm No Angel, which stars Mae West and Cary Grant and costs a mere 35 cents (or a quarter for members). The weekend continues with two Franks: Borzage's Hooverville classic, Man's Castle, and Capra's punchy American Madness. I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the new print of the Borzage and wrote up some quick thoughts for The Auteurs' Notebook, which you will be able to read

To counter our chill with a laugh (and a hug?), Film Forum has programmed the Breadlines and Champagne series, a month-long celebration of Great Depression cinema. The fun begins this weekend with an opening night screening of Wesley Ruggles' 1933 film, I'm No Angel, which stars Mae West and Cary Grant and costs a mere 35 cents (or a quarter for members). The weekend continues with two Franks: Borzage's Hooverville classic, Man's Castle, and Capra's punchy American Madness. I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the new print of the Borzage and wrote up some quick thoughts for The Auteurs' Notebook, which you will be able to read  But don't stop there. Scroll down that page and you'll see all kinds of fun double bills, all at a 2-for-1 discount, including one helluva Valentine's Day, programmed by Bruce Goldstein to pair My Man Godfrey (service would save the day, wouldn't it) with Easy Living (perhaps most famous now for its early Sturges screenplay). If that kind of night out (complimented by a meal and drinks, if not flowers, I trust) does not warm the soul, I cannot imagine what will. Of course, two days earlier there's a new print of Young Mister Lincoln screening with The Tall Target, if your soul needs that kind of uplift. Night Nurse plays Feb 17, Hawks' Scarface on the 21st and King Kong helps close the month before five more double bills to start March. I'm going to try to enjoy as many as my meager wallet and my stuffed social calendar will allow. (And if that's not enough for you, there's something called The Human Condition coming back by popular demand April 8th. That one might tell you some things.) [x-posted at the curator corner]

But don't stop there. Scroll down that page and you'll see all kinds of fun double bills, all at a 2-for-1 discount, including one helluva Valentine's Day, programmed by Bruce Goldstein to pair My Man Godfrey (service would save the day, wouldn't it) with Easy Living (perhaps most famous now for its early Sturges screenplay). If that kind of night out (complimented by a meal and drinks, if not flowers, I trust) does not warm the soul, I cannot imagine what will. Of course, two days earlier there's a new print of Young Mister Lincoln screening with The Tall Target, if your soul needs that kind of uplift. Night Nurse plays Feb 17, Hawks' Scarface on the 21st and King Kong helps close the month before five more double bills to start March. I'm going to try to enjoy as many as my meager wallet and my stuffed social calendar will allow. (And if that's not enough for you, there's something called The Human Condition coming back by popular demand April 8th. That one might tell you some things.) [x-posted at the curator corner]

UPDATE: My piece on Man's Castle is available over here, and I've left a comment below the "essay" that furthers my thought a bit, or questions what I've written, in an inviting way (I hope).

UPDATE THE SECOND: My first piece published at SpoutBlog can be found through this link. It's called "Valentine's and Breadlines: Love in the Depression" and it concerns a few of the romantic comedies I've seen in the past week at the Film Forum. Please, read it. Please, tell me things. Please, enjoy your Saturday.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:00 AM

0

grooves

![]()

Labels: America, blogging, Borzage, Cary Grant, criticism, linkage, rwk, Spencer Tracy, Spout Blog, The Auteurs

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Dardo Department

by Ryland Walker Knight

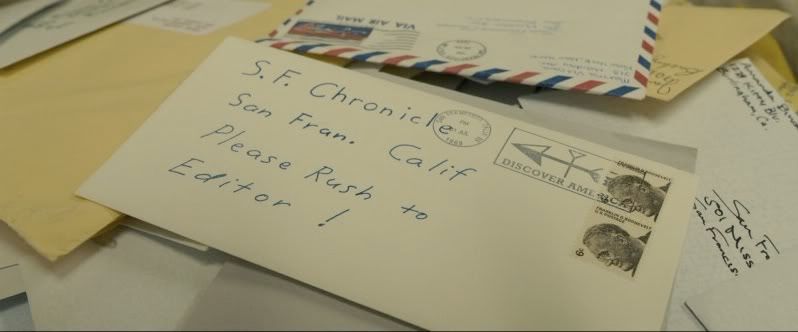

by Ryland Walker Knight

Say, who knew? Well, one friend did. She sent along word that MONDO DIGITAL, at some point in the recent past, tagged VINYL IS HEAVY for a Premio Dardo Award. Now, Glenn Kenny already nodded at us a lil while ago, and we are very wary of these "meme" things, but we also adore attention like anybody else, so, heck, why not bask in it some, right? Which is a way to say thanks. Apparently there are some "rules" we are supposed to follow, like "tagging" other people/bloggers, but since most of my blogging buddies (like GK) have already been tagged, I'm just going to direct you to the "We Tight, Presumptuous" blogroll to the right and say that we are (hell, I am) honored to be friends, or at the very least friend-ly, with all those listed there. If I were to single out one of those, though, I'd point to my good friend Brian Darr of Hell on Frisco Bay as I've known him the longest (of the boys; I've known Megan since high school and Mia since I was her boss six or so years ago), and he's helped direct my cinephilia more than he probably knows. When Brian "accidently" deleted his blog one day, I was floored and worried and immediately wrote him something like eight e-mails trying to make sure he would continue his new media text-based documentary of a certain film-going history that this blogging world and his efforts therein make available. I went so far as to say: "If you're done with your blog, which I hope you are not, do you wanna install a column on VINYL?" Lucky for all of us it only took a couple weeks to get everything straightened out and we have, in the time since, gotten that much more great stuff from him. Including, on a selfish level, his participation in not just one but two episodes of VINYL IS PODCAST (which we hope will resume soon enough): No. 2, on the rep calendar, and No. 9, on the avant-garde. So, thanks, buddy! I miss seeing movies with you!

— I also leave this open for my fellow VINYL contributors, and friends, to point to some of their favorite blogs in the comments, which I can then port up above into the body this post if such friends and colleagues so desire.

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

8:00 AM

1 grooves

![]()

Labels: blogging, Dardo Awards, linkage, rwk, VINYL IS PODCAST

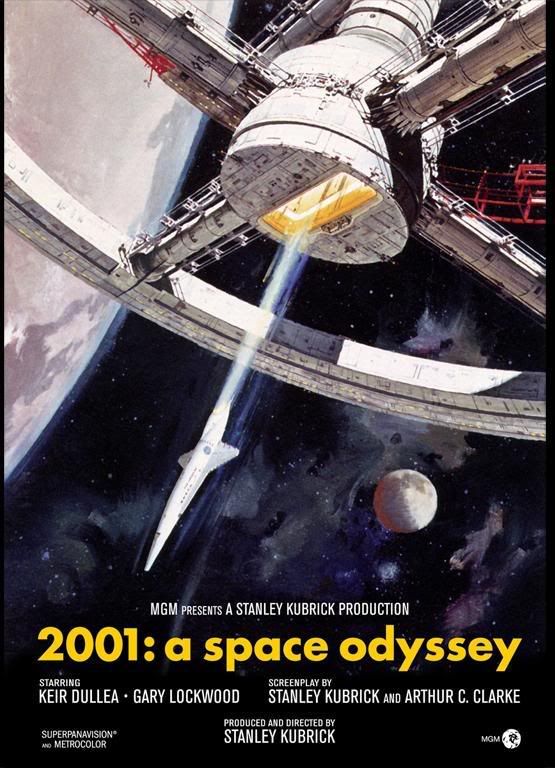

10 Personal Touchstones in American Cinema

by Ryland Walker Knight

[Originally posted at the curator corner, where you can read the full post.]

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

7:30 AM

0

grooves

![]()

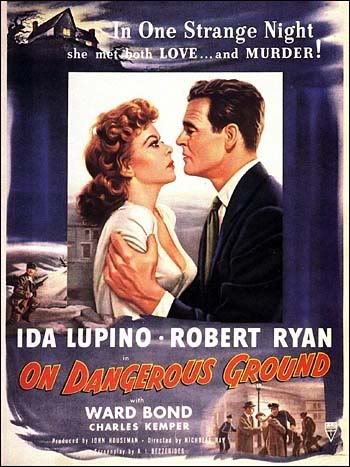

Labels: America, blogging, David Lynch, Francis Ford Coppola, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Leo McCarey, linkage, list, Nicholas Ray, rwk, Scorsese, Terrence Malick, Wes Anderson, Woody Allen

Monday, February 09, 2009

In the works: Doillon at FIAF.

by Ryland Walker Knight

Last Tuesday marked the beginning of the current Jacques Doillon retrospective at French Institute-Alliance Française with a screening of 1985's La Vie de famille, which Dan Salitt says is lovely. I missed it, and I'm bummed. However, I can say that tonight's film, Le petit criminel, is well worth seeing if you happen to live in New York City. I hope to have some words formed about it, and next week's Ponette, for your reading pleasure at The Auteurs' Notebook soon. I'll keep you updated. What's most striking, so far, looking at Doillon's cinema in the order of its programmed appearance at the FIAF, is the focus on children—and their complete "naturalness" in front of the camera. The close-up effaces, or makes transparent, any masks they (wish or hope to) wear. Set mostly in a two-door almost-truck, Le petit criminel is meager, and subtle, a restricted (head) space prone to jammed signals, to cluttered thoughts. The endgame may appear "open" to some but, as the cop says earlier in the picture, there should be no doubt as to where the story winds up; how the angles converge and how the camera pushes into that space (as well as away) define its characteristic (to say, stubborn) resilience. I can only guess how this plays out fuller in La vie de famille, as this trailer below hints at a film teeming with a lot of things I love, like Juliette Binoche, words, language, direct-address, diegetic video use, family problems despite good intentions, life's inherent corruption (and corruptibility), Sami Frey all man-like some 20-plus years after Godard had him dancing all boy-like, and so on; my attraction should become readily apparent as you click play.

Since I'm following the screening schedule, kinda, this puts my viewing of Doillon's films of the 1970s back a bit in my personal queue. This is fine by me, of course, as I've subscribed to a certain curriculum, if you will, but it makes it a little harder to gauge at this point how much similarity his work bears to those of his post-vague filmmaking brethren (the press release mentions Eustache and Garrel to get nerds like me excited) over against a larger tradition of gallic cinema. So far, it seems like he's got more to say to Truffaut and Pialat than those other dudes. More soon. —Oh, and a quick thanks to all the ideas and thoughts thrown my way in that last (now enormous) thread at Girish's joint. [x-posted at the curator corner.]

Friday, February 06, 2009

Saturday School: The Class Structure, or, Procedures of Breaking Down.

by Mark Haslam

It's strange—yet strangely on—to call Laurence Cantet's Entre les murs (The Class) a procedural. Strange mostly because it envisions teaching as improvisation, as precisely those moments when structure and procudure break down. Here, at communication's end, communication can (it hopes) begin.

...

We enter the class through its teacher, François Marin (played by François Bégaudeau, who lived and wrote the book on which the film is based). The camera follows him into the school, maneuvering the halls, picking up movement as profs set up their classrooms: one body bumps into another, darts through a doorway; a table is hoisted up and out of a room. It's exciting, excited, and anticipatory. Of course, much of this has to do with the fact that the kids've yet to arrive.

With the ringing of the first bell, movement/expectation shifts—to the students, yes, but, more importantly (and we can also say, as a result)—to language. The film is constructed around language and its potential to be played. So it's only fitting that the class we attend is a French class. Here, as in our English classes in America, kids are tought to deal with 'proper' language 'properly'. This, as an initial situation, results in tension—a tension immanent to power structures, where the idea of there being a way comes up against multiple, other ways. In The Class, in any class, really, the struggle which emerges from this tension is linguistic. (When Cantet, in an interview with Phillipe Mangeot, refers to a particular “scene where [François] answers that the difference between written and spoken language is a question of intuition,” we should perhaps hear the final word also as institution.) When M. Marin first introduces himself to the class, for example, the students instantly set to punning off of his name, beginning the language game that propells the film.

The teacher, however, plays the game with a disadvantage. He's isolated: spatially, for one—which allows, here, an occassional note to be passed, there, a stifled snicker, whisper, etc.—and second, bound by institution, socially—the constant evolution of language results in “lacunae,” as Bégaudeau calls them, ever opening between student and teacher. Yet François does not take the institution's approach to the emergence of these lacunae. He neither quells nor ignores them as threats to system, but recognizes, pursues, and actively engages their emergence.

Teaching is a navigation of the lacunae and the two bordering spaces. The pursuit of gaps in light of system's failure.

...

A scene's inception: a lesson plan, a question.

Follow the gazes: they cross, but don't ever really meet; they branch (but from where?). There's something chaotic about their pattern, as lines in a Bunimovich Stadium. “[A] school is sometimes very chaotic,” Cantet notes, “useless to cover its face, there are moments of discouragement but also moments of grace, immense happiness. And from this great chaos, a lot of intelligence can be born.” Existing between the walls, a bounce and redirection occurs over and again. The lesson plan proposes a direction. Its desire is to impart direction itself. Each gaze, in turn, proposes its own direction, or rather, holds the potential for a shift. With a question, the potential is realized; chaos emerges in/as language.

Cantet's process mirrors these gazes: “...what we planned to do would require three cameras: a first, always on the teacher; a second, on the student at the center of the scene, and a third prepared for digressions....”

Each camera, which together compose The Camera, entail both a structure and its unraveling. One eye trained on matters at hand; the other, rolling and wandering as if of glass. Entre les murs builds itself out of its own disregard. Through these cameras, seeing becomes a component of chaos, but also forms chaos into a pattern. When François pursues the students tangents and diversions, it's to make them no longer tangents and diversions. It's to make chaos the thing. He acknowledges a certain flow and flux within (the, this, any) class: the moments before the Big Bang, approaching phase transition, before a something emerged. The scenes that result from transitions aren't a part of any narrative, rather they're (linguistic) events. Parts composing a whole—individual acts of creation and resistance. Random, no doubt—like the appearance of language itself from sound and tone. But taken together they form, even in breaking from system, their own structure. The structure of a game, but nobody wins out. Nobody can, but nobody needs to.

...

So, yeah, structure must be set aside. Teaching must fail in order to continue. Okay. But Entre les murs isn't Dead Poets Society. Nor is it Half Nelson or Finding Forester or whatever. It doesn't want anything to do with life lessons and breaking from tradition and inspiring those poor, underpriveledged kids. Every moment of success is followed by a moment of failure: As soon as the class's official troublemaker, Souleyman, displays a moment of brilliance, or at least a moment of hope...a different incident leads to expulsion proceedings. Teaching's limits frame each image—are, in fact, often conflated with its successes. The film doesn't demystify the profession; it just approaches it without illusions. It documents, in other words. Here, finally, we see it as a procedural. A real desire to show everything about teaching emerges at the center. And though words like “real” or “accurate” may cause some cheeks to blush, I want to use them.

But, then, the reality of a school is performance. To be a teacher, to be a student (in middle-school, no less, where masks are the most colorful and the most varied) is to act. So, really, it's not hard to believe that the teachers and students in the film aren't actors, but are teachers and students—mostly because, well, they're so believable. Improvisation is what their stations already require of them. The film's desire to document, to unfold procedures, reveals this theater. School, sure, but more: “a sounding board, a microcosm of the world...”

...

The film ends with images of the empty classroom. Sounds from outside, where life continues to an impossible order, sift through the windows. Desks remain, but disarrayed—remnants of chaos in pieces of institution. And the cameras which documented the students? The year's procedures and performances having ended, they're just rolling. Or are they waiting? Is this perhaps not a winding down, but a gearing up again? The shouts and screams coming in from beyond are language before language, and so the potential remains between the walls—a space neither in nor out, but within the gaps that emerge between here and there, where chaos, which is seeing, becomes the lesson.

This is where learning happens.

[The Class opened at The Smith Rafael yesterday after limited runs in New York and Los Angeles. Sony plans to roll out the film further as it has been nominated for Best Foreign Film in this year's Oscars. Check your local listings. Learn something.]

Thursday, February 05, 2009

Quick Plug: the curator corner

by Ryland Walker Knight

A word to the wise: starting today, in tandem with a new venture, I'm hitting a new blog space with daily enthusiasms. It's called "the curator corner" and you can find it right here. That new venture? I'll be helping out at Art+Culture as it prepares for a relaunch in the coming calendar year. We are currently in private beta. If you're curious, which we trust you shall be, drop us a line and come play with some of our tasty tool set. See you there!

[PS— Don't forget The Che Letters!]

Wednesday, February 04, 2009

The Che letters. Part Two: Canyons, Circles, Exiles

by Ryland Walker Knight

[A note: Here we continue what Mark began back in Part One. (To see all the letters, click here.) We hope the letters continue, as we push forward into 2009, because we find this epic so typical of our (yes, fetishistic) interests in cinema as a tool for and of history; and of our aims as intellectually curious people of and in the world in general. I should like to say that these missives are hardly "polished" for a couple of reasons but that should become transparent soon enough. For instance: we are not done. Stay tuned for Part Three in the coming weeks.]

Mark,

Your impulse to talk around the subject as a way to talk with the subject seems to mirror how Soderbergh's film works, of course, but what makes the film so curious to my eyes and ears is, first of all, how committed to its subject it remains. For all its distance, Che is rather intimate. For all its landscapes, the close-up figures into a large part of its argument. However, the close-up operates in (if not diametric then perhaps) divergent registers across the film's intermission rift. In Cuba, the close-up is pure affection, luminescent and loving expression; in Bolivia, close-ups catalogue and segregate elements of the whole. In both halves, these sets form a crucial part of Che's balance-equation in that their uses are explicitly related not just to form but how we witnesses will figure our "hero" at hand.

Reading Hoberman's essay in The Virginia Quarterly Review shortly after reading your first missive made me think twice about your preliminary assumption-declaration that "Che is not about Che." His essay begins with two weighty words for this man: "Ecce homo," which, of course, nods at Nietzsche and declares, with a colon, "this man." This man, Che, who means so many things. Hoberman lists a number of them, all fine labels, all fine in concert with each other, just as our sense of Ernesto Guevara is folded by so many forces of history and commerce and theory and philosophy and tradition and understanding and all tied to a single image appropriated (I want to say "abused" or even "slaved") into base, reductive, limited symbolism. My list here, as a response to Hoberman's, is an attempt to account for all those contradictory angles played in some name that really only means one thing at bottom: "man." It's redundant: this movie is about man, not just this man, but, of course, it can only ever be "about" this man in particular. And, as Hoberman astutely points, this man is a means for Soderbergh to explore personal obsessions such as process and technique. Look at any one of Soderbergh's films and you will find he is, indeed, or more than less, "a highly intelligent technician who sets himself a problem and goes about solving it."

Again, your question: how, if at all, do we approach Our Man, That Man, This Che? If we may see Che as mathematics, as Soderbergh has arranged it to rise and fall like the sun, that ever-reliable reminder of our finitude, then perhaps we should do well to grant science its place at this martyr's table of conversation. No doubt the masses have silkscreened the Guevara myth to a new death, or depth. No wonder the aura is drained. No surprise Benjamin comes to mind. No way to get around the repetition of Che. No modulation subsumed in total, the differences are shifts, the revolution a series without end: a perpetual reformation.

Others have said we must let the singular stand free, we must cherish and preserve these rarities. This challenge has largely been ignored by many of our (intelligent and critically thinking) colleagues. The exciting thing about Che is that, as a hermeneutical situation unto itself (as any work of art is, or can and should be), it rejects a lot of the strict language of closed or isolated subjects—here I think of Sartre as the great mis-reader of Heidegger, and of Gadamer's lucid restorations—but rather an appeal to vulnerability, to the allowance for failure that participation wills us towards, or simply makes impossible to avoid. Here is my humble proposition that the freedom Che argues for, while not that of Che's per se, is one where (useless though it may resound) tragedy looms. However, I do not want to say the film is defeatist. It may deny, but it ends on a boat, looking to the future (from the past), past a spray of light that triggers a reverse shot back at Our Che, standing bowed on the starboard side sharing fruit and looking wary at us, we whose gaze forges him as we wish.

The film is opaque yet transparent. A typically "academic" double move. And, indeed, Soderbergh's work is attacked as "academic." When will this cease to be a pejorative? When will the many under-readers—it's funny that those who tread the surface are hardly interested in a hermeneutics of surfaces and seek only to uncover the unknowable with an arrogance unavailable to my wary posture—begin to appreciate the fact that over-reading is, well, a virtue born of thoughtful attention to the world and its multifarious blossoming forth? When might we see the "real" revolution something like our blogosphere provides? When shall we shuck the calendar's arbitrariness to slow our rollout? When a real Marxism props up somewhere? —When will we get around to talking about the film?

I often wonder if my interest in film has mutated into an interest in what film, or a film, provides in aftermath. I know this cannot be fully true as I do, indeed, keep watching. My watching has slowed so much in the past years because my watching now involves countless re-watching, revisions of my visions. I've said before on this blog (well, in a podcast) that the hermeneut's project is a compulsion, and it may not be healthy; I meant this to encompass cinephilia; this is old news. All of this to say: I do enjoy watching Che. I find Cuba gorgeous, if occasionally on the nose and a tad "cute," and I find Bolivia devastating, and quite often yet more beautiful than its counterpart for all its drain, its pale weight of time and its canyon-cinema-circles. I find Benecio Del Toro's performance pitched perfectly between sex symbol and myopic asshole. I find Soderbergh's mise-en-scène has not been this rigorous since his under-loved revision of Solaris—which features similar arguments about beautiful, stubborn men contending with martyrdom and love and the process of history, or memory-making (all themes shared by his great, deft The Limey; in fact these themes emerge present in all his films). I find the whole 257 minutes easily "too much" and nowhere near "perfect"—it's a "rush job" as much as Hoberman's "act of will" although it cannot nor should it ever be rushed. I find it impossible to recommend.

Che is foreign to itself like Che is forever foreign to his environment. His yearn for a united South America (present before Cuba, if hardly seen here, and announced throughout Bolivia) can never translate in practical terms for the simple fact that his fellows can never look past his face, his spectacle as a figure or a symbol. His comrades do not see his true singularity, his freedom of himself. Soderbergh may know he has no place in the world Guevara sought to build but he also knows that what we all look to Che for is that image of freedom that, as it is unavoidably poetic, comes only from exile. It's a negative freedom, if I understand, and, in a hilarious completion of one circle, a positively American picture that asserts our rights as humans to be a little crazy, to shuck rationale. Because, of course, freedom concerns our world, and not just humans; a space unanswerable to conceptual schemes, to maps of thought; a space given to productivity, to becoming made possible by our limits. Fitting, then, that Che is situated by a pair of maps. Boundaries mean something. Che sought transcendence and all he got was an ignoble death in a hut. His myth, on the other hand, necessarily separate, keeps gaining. If Soderbergh's film can do anything in that space, perhaps it can remind us that this was a man and that man, like this world, will pass into history; however, if we look to build something we have already taken a step towards something.

Until then,

ry

Posted by

Ryland Walker Knight

at

9:01 PM

2

grooves

![]()

Labels: Che Letters, close-ups, exile, freedom, love, revolutionary, rwk, space, Steven Soderbergh