by Ryland Walker Knight

[This essay originally appeared in German, as seen below, in Cargo No.4. The film is long gone from theatres, but it will hit DVD next week if you still want to see it.]

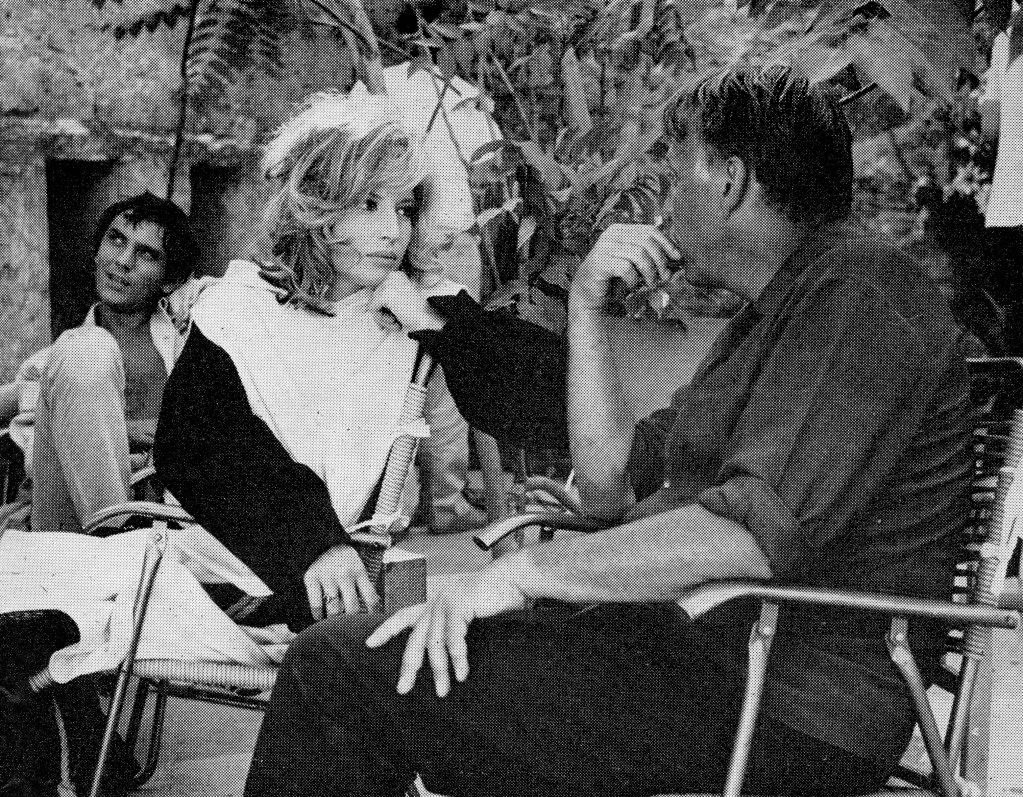

Funny to find Jane Campion, now, getting chaste with

Bright Star after her previous feature,

In The Cut (2003 sounds so long ago), dripped with sex. Which isn’t to say

Bright Star is sexless, or not sexy; rather, desire is couched in words and fabrics. The social sphere, here, limits advances and, most surprising, economics determine the course of events. If there’s any feminist push to this film, whereas

In The Cut pushed everything, it comes from literal subtext—asides, contrivances, allusion—though the basic premise of a stout young lady demanding to live and love without care for reputation fits the bill. No doubt, the film belongs to Abbie Cornish (she plays that fickle muse, Fanny Brawne) more than Ben Whishaw (he’s our poet, John Keats), as her performance is subtle and strong in all the right ways, directing our attention to how this bundle of emotions called a poet came into and out of her life, how it affected

her path. But, at heart, which is to say despite that slant,

Bright Star is a simple love story.

Flirtation starts and stops until the pair wind up kissing on a river bank and it’s all-in from there on; in fact, as befits their age, their love affair is perfectly adolescent, all devotion and no questions, every feeling feeling bigger than life. They write letters, they pine, he writes poems and she sews couture clothes. The film opens with Fanny sewing, alone, in a room of her own, before the Brawnes pay visit to the home of Charles Armitage Brown (Paul Schneider gambols through his role behind a beard and garish, plaid trousers). Fanny wears a brilliant red top of her own design. She’s marked from the start as apart, refusing the drab palate around her: Campion frames her in the center, no less, a focal point of color in a brown and muddy world. Further, she refuses the boyish baiting of Brown, steadfast in her fashion, flipping his taunts back onto him with a needling “And I make money at it” to mock the poet’s plight. From this beginning, Brown is host to Keats, and Keats is host to a cold, laying low outside the social call. We meet him with Fanny, as she brings him tea, and their game starts here—for he, too, has never made money with his art. And of course he never does.

Keats financial woes are the crux of the struggle for this love affair. As custom dictates, Fanny is discouraged from considering Keats as a lover for the simple, typical fact that he has no prospects with which to marry her. His poems hardly sell (we meet a book seller with overstock), and he’s frail; he lives with his friends and he has no family, really, after his brother dies. He lives by Brown’s side, by Brown’s generosity, living in constant debt. After a snowy trek home from London in a thin jacket he falls ill. Given his state—of funds, of health—his friends pay his passage to Italy hoping the milder winter weather will help buoy his condition. This plan, of course, proves a lost cause and Keats is lost, another poet sent penniless to the grave only to turn evergreen in another era.

Fanny grieves, in blue-gelled frames, and goes for her own walk in the snow, all properly bundled, to recite a poem her beau had written for her, about her. She’s wearing black to rhyme with the naked branches above her, and her bonnet is a pall, not a halo, as she crosses the bottom of the frame (Campion angles up from below), leaving the image empty a beat before the final cut and the credits begin to roll. The credits, as it happens, are a highlight of the film despite the lack of filmmaking: Ben Whishaw reads “Ode to a Nightingale” in its entirety over the scroll. Here Keats' words come alive in ways Campion can’t figure. For here we hear the words—they are given space in the near-black of the theatre—and they sink images into our ears. Throughout the film, Keats’ words compete with Campion’s images, which cheapens both. Campion is a sensualist, an undeniable image-maker incapable of turning light dull, tied to color and composition, to the play of focal lengths; she is a filmmaker of proximities. Keats created images, too, of course, crafting affective paeans to immanence and to emotions, indeed to romance. But their methods are at odds with one another when placed against/over one another. Instead of pretty, the picture becomes “pretty.” Despite the insistent wordplay of

In The Cut (Meg Ryan’s Frannie, natch, is a junior college English professor obsessed with slang; nearly every bit of dialogue’s a double entendre), it’s an image movie: color and bodies and fluids make it work, push it forward and farther into deep and dark corners of lust and luster.

Bright Star wants to be about the word, and its epistolary sequences seem to work for the most part, but Campion’s romantic images (fields of purple flowers; Keats climbing a tree for a dusk-lit stretch on top of its branches; Fanny surrounded by butterflies) become postcards, to say tidy signposts, when layered with Keats’ words. Every image is beautiful, but each is almost ostentatious.

The performers save the picture. It’s Cornish, playing wounded, who turns love letter despondency from indulgent bathos to genuine pain. It’s Whishaw’s wry and wiry frame, his elfish smile and curious-though-quiet voice that changes a recitation into a seduction. Indeed, if these two were not so beautiful, their mutual infatuation would just look fatuous. Paul Schneider, though, is the secret. He seems heavier with his beard and his pot belly, though it may be swishy, looks like a real load. His Irish brogue is not light, but his pride and his bluster and his quickness to laugh help make his Brown not just an ape of loutish vulgarity—though he often is just that—but another devotee whose love is reigned in by his own mistakes and shortcomings. His unguarded admission of guilt, declaring for Fanny that he failed his friend, is right plaintive as his voice mounts louder and he kicks a chair off screen to quell his tears.

Such loss forces evaluation, and such “failure” as Brown’s begs the question of capitalism, of debts. A life cannot be valued in accounts. Neither joy nor passion is quantifiable. Perhaps that’s the value of

Bright Star: to reaffirm the qualitative—to show the luxury of a lounging intellect against the incalculable commoditization of thought—over the demands of the quantitative in this ledger world we live amid. Because, as much as it’s a tragedy that Keats died so young, the real tragedy

Bright Star would have you believe is that he died alone, or at least away from his Fanny and his friend Brown. Not only was his potential never fully tapped, but it dripped spent in near-solitude. The cost of the trip proves not economic after all, but pathetic and affective. That’s the film, too, we realize: flattery and shame for all struggling nobodies, a reminder of our clichés despite the will to individuality; for it is precisely one’s characteristic spark, what defines our singular imprint, that we cannot appraise; our light, we hope, shines steadfast past us to tie together all us wayward eremites. The privilege of this pair, we might say, is that they found a fabric more luxurious than most, however brief. But that’s pretty romantic, isn’t it?